Guide to Archival Holdings /

Our collection has been coming into being

as long as our organization has. Holdings include anything relating to The New

Gallery that staff saw value in preserving, including ephemera from our

programming, internal communications, correspondence between our staff or

volunteers and artists, and reference material on artist issues gathered by TNG

members since 1975. Visit the evolving finding aids below ︎︎︎ for an idea of what

is available.

In 2008, a collection of documentation relating to The New Gallery’s founding, organization, board materials, histories and reports, was deaccessioned to the Glenbow Archive for custody. If you are interested in material pertaining to the founding and early organization of TNG, visit the page for this collection at Alberta On Record.

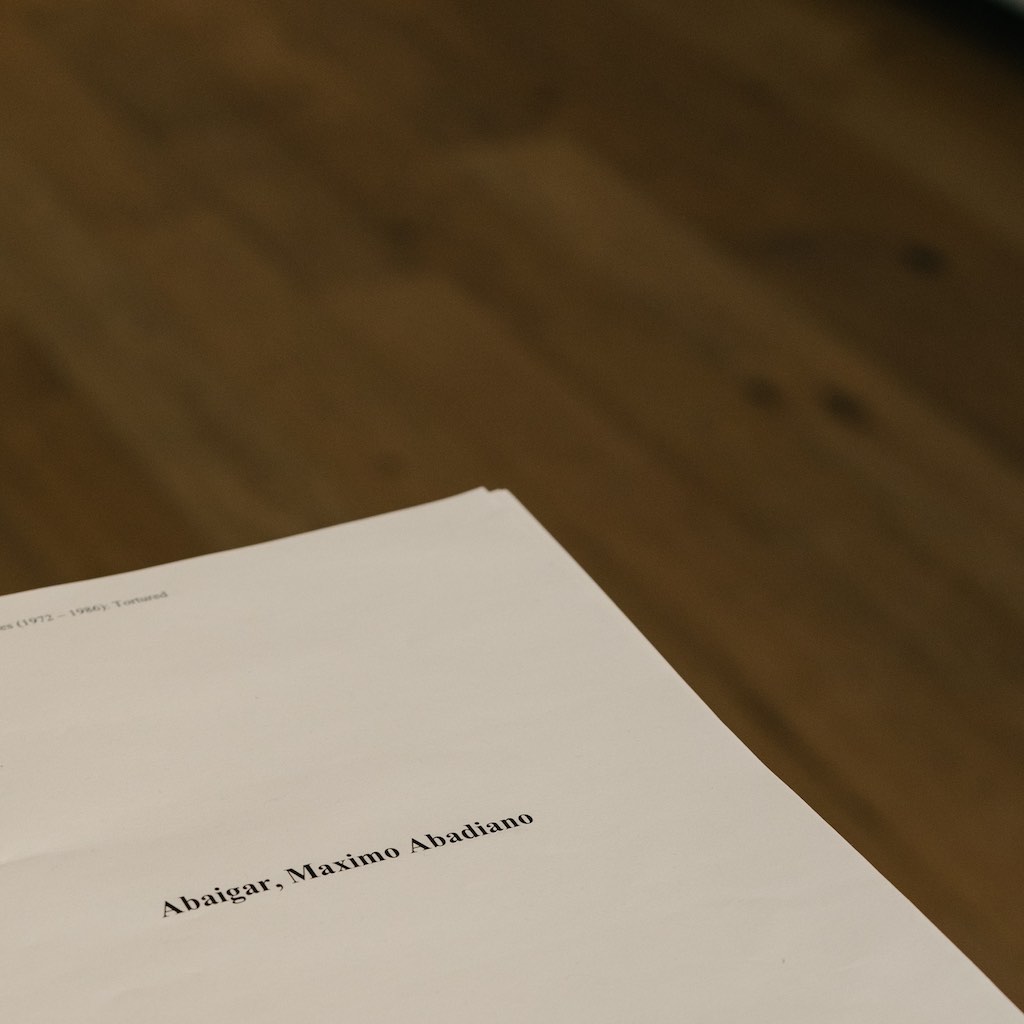

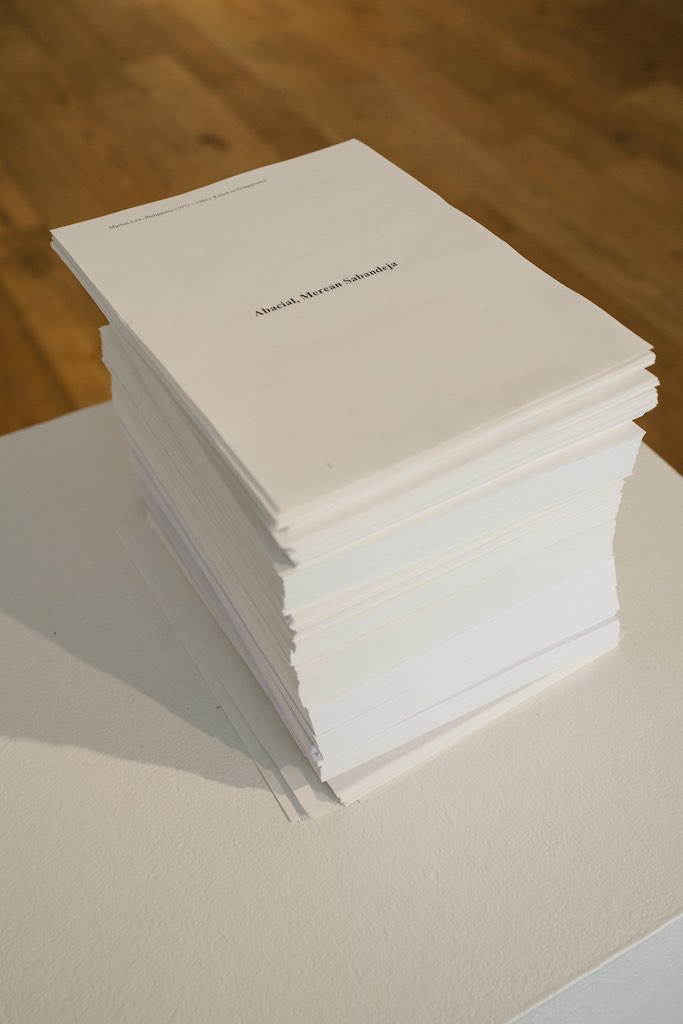

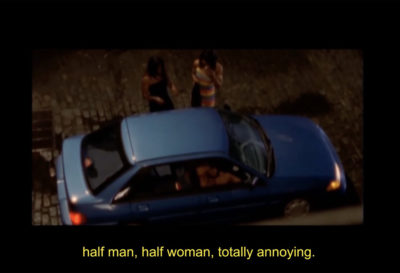

Our most extensive collection is our artist and exhibition files. These files are continuously updated, with a folder added for every new exhibition. These collections are also in the process of being made fully available online. You can browse those already digitized by artist, year or exhibition location and type by using the links on the search page. If you browse by artist name, you will also find folder numbers corresponding to the physical archival files we hold about that artist. Occasionally, everything in that folder has been digitized, but often, further material is available for perusal in the physical file. If you’d like to browse the contents of these archives, please make an appointment by contacting one of our staff. They will pull the files you are interested in for your visit. Please cite the collection in your research with: [folder number], The New Gallery Archive, The New Gallery, Calgary.

In 2008, a collection of documentation relating to The New Gallery’s founding, organization, board materials, histories and reports, was deaccessioned to the Glenbow Archive for custody. If you are interested in material pertaining to the founding and early organization of TNG, visit the page for this collection at Alberta On Record.

Our most extensive collection is our artist and exhibition files. These files are continuously updated, with a folder added for every new exhibition. These collections are also in the process of being made fully available online. You can browse those already digitized by artist, year or exhibition location and type by using the links on the search page. If you browse by artist name, you will also find folder numbers corresponding to the physical archival files we hold about that artist. Occasionally, everything in that folder has been digitized, but often, further material is available for perusal in the physical file. If you’d like to browse the contents of these archives, please make an appointment by contacting one of our staff. They will pull the files you are interested in for your visit. Please cite the collection in your research with: [folder number], The New Gallery Archive, The New Gallery, Calgary.

Finding Aids

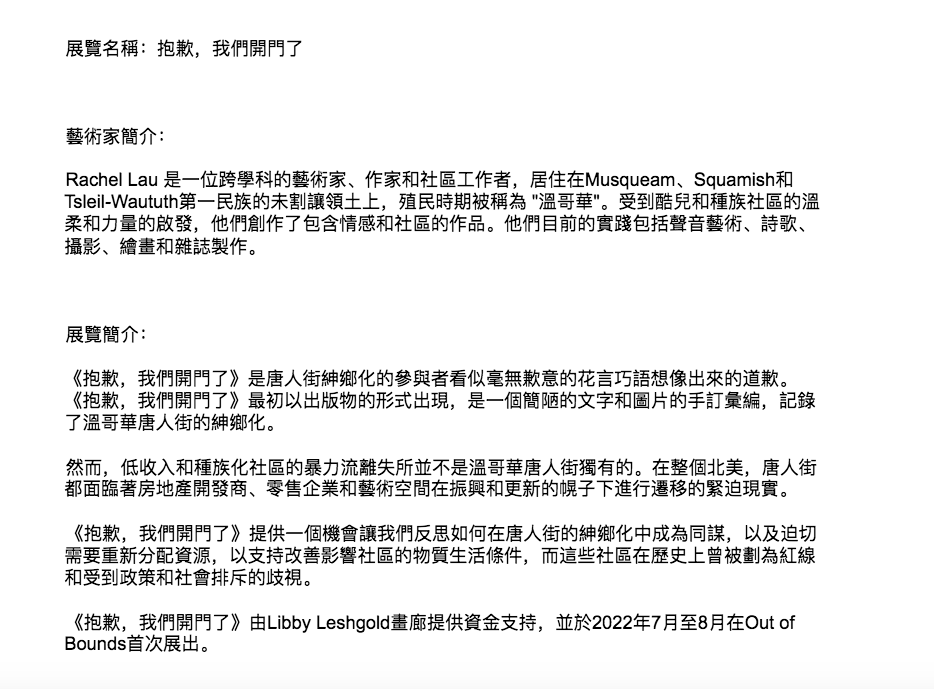

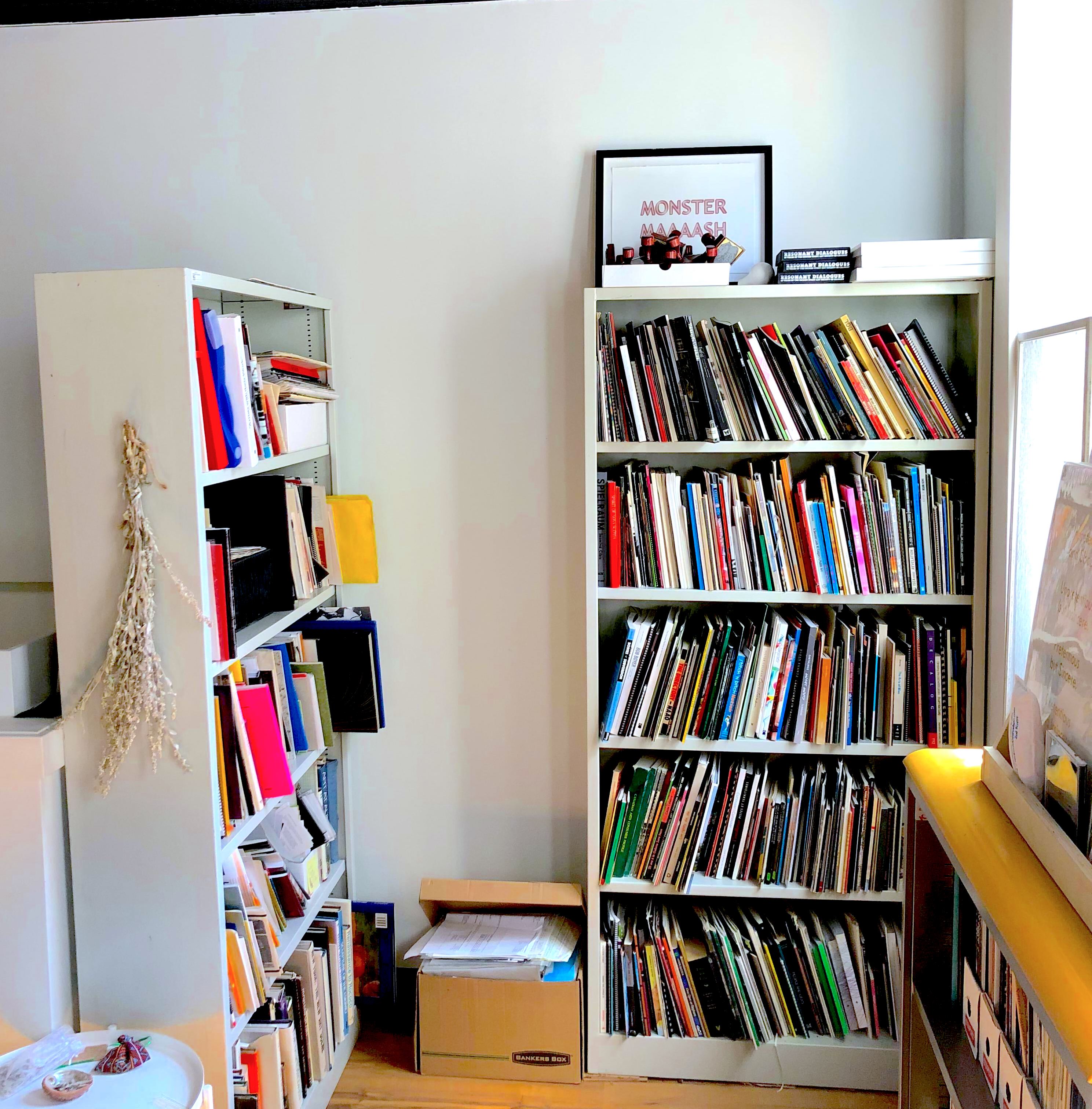

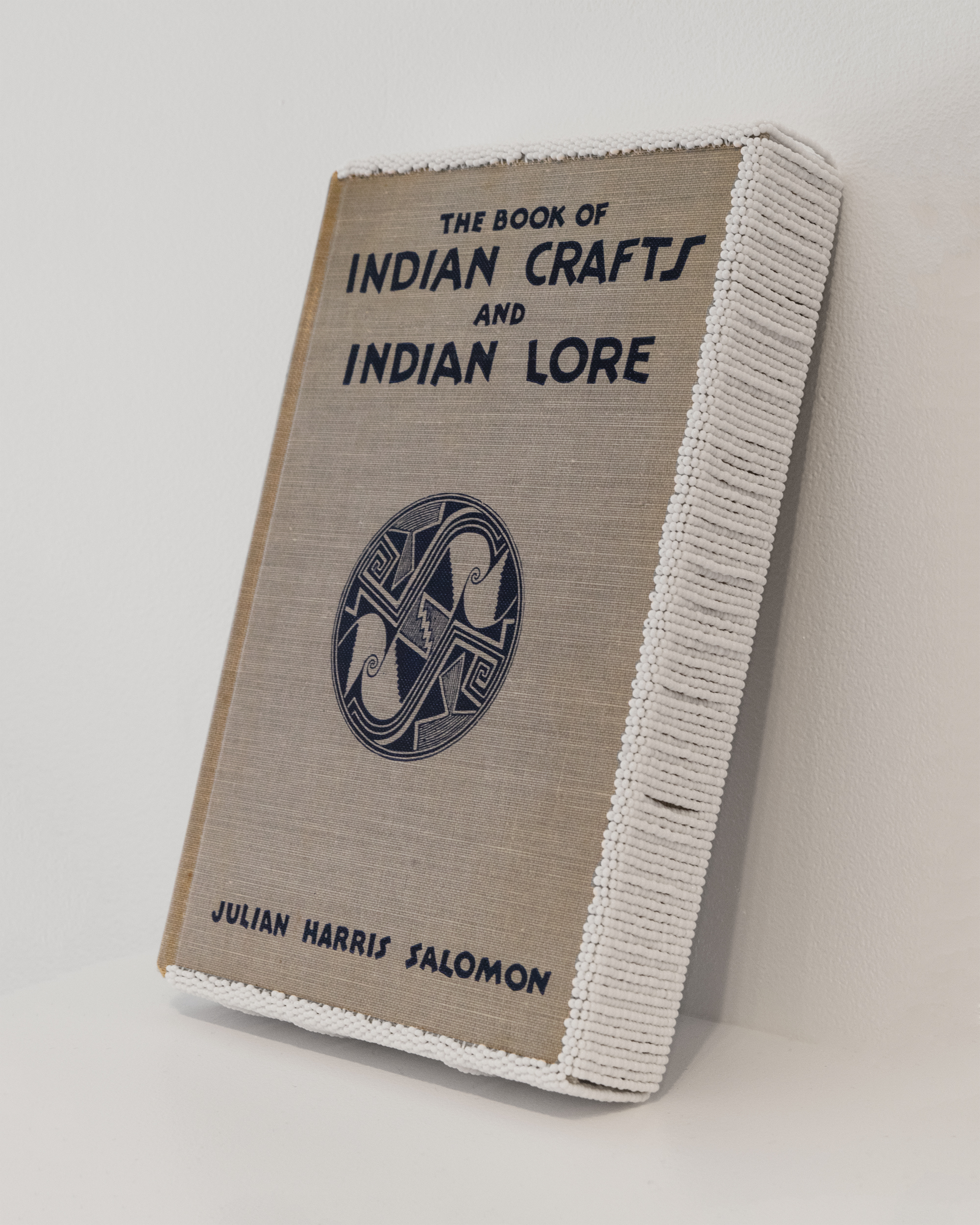

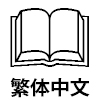

Library /

The resource centre library is currently

open for browsing and undergoing an organizational process. Books acquired by

The New Gallery have a focus on visual art, and can be used for artistic

inspiration, reference, or curatorial context. Books include art history

surveys, craft typologies, monographs on artists, and artist books, both small

and large. This collection occupies two shelves in the resource centre. The

library also holds a variety of art magazines, collected by staff and

associates throughout TNG’s history. An updating spreadsheet detailing our

magazine collection and book collection may be downloaded below ︎︎︎

Our library is still very small, so we do not currently have a program in place for borrowing from our collection. We also currently do not have a full list of holdings for our library, but our small collection is meant to be browsed. All are welcome to book the resource centre during office hours to explore our library and archive. To book time in the resource centre please email our Programming Coordinator, Jasmine at Jasmine@TheNewGallery.org

Our library is still very small, so we do not currently have a program in place for borrowing from our collection. We also currently do not have a full list of holdings for our library, but our small collection is meant to be browsed. All are welcome to book the resource centre during office hours to explore our library and archive. To book time in the resource centre please email our Programming Coordinator, Jasmine at Jasmine@TheNewGallery.org

The New Gallery / Archive

Exhibitions by Location:

︎Main Space

︎Billboard 208

︎Mainframe

︎Offsite

︎+15 Window Exhibitions

︎Artist Trading Cards

Search Exhibitions:

︎Programming by Artist (Surname or Group)

︎Programming By Year

Programming by type:

︎Events

︎Public Programs

︎Artist Residencies

︎Fundraisers

Archival Guide

Collection

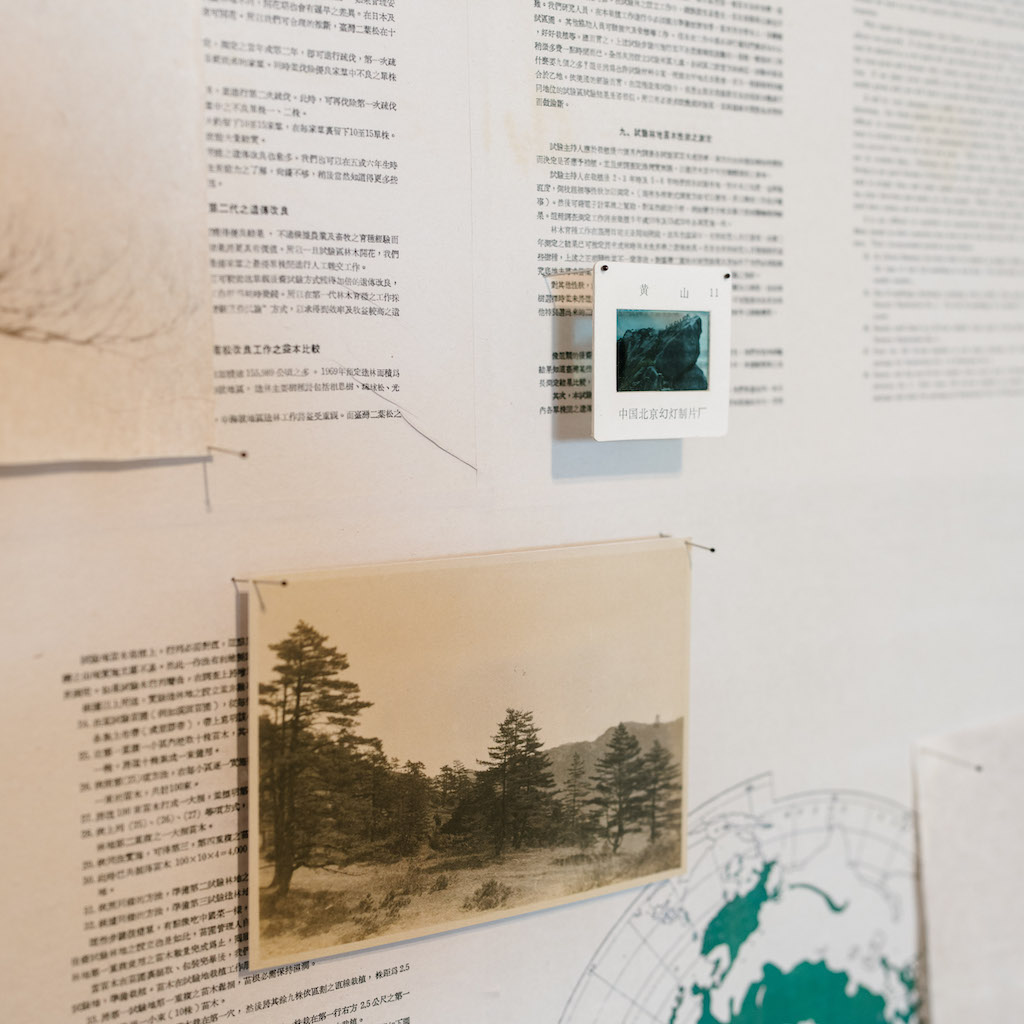

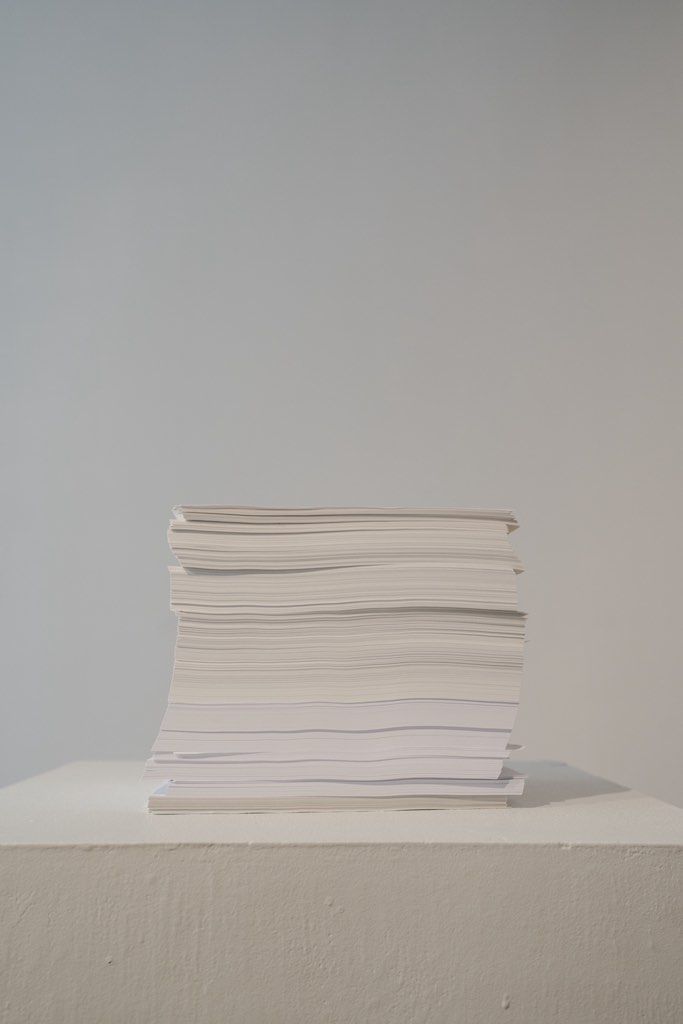

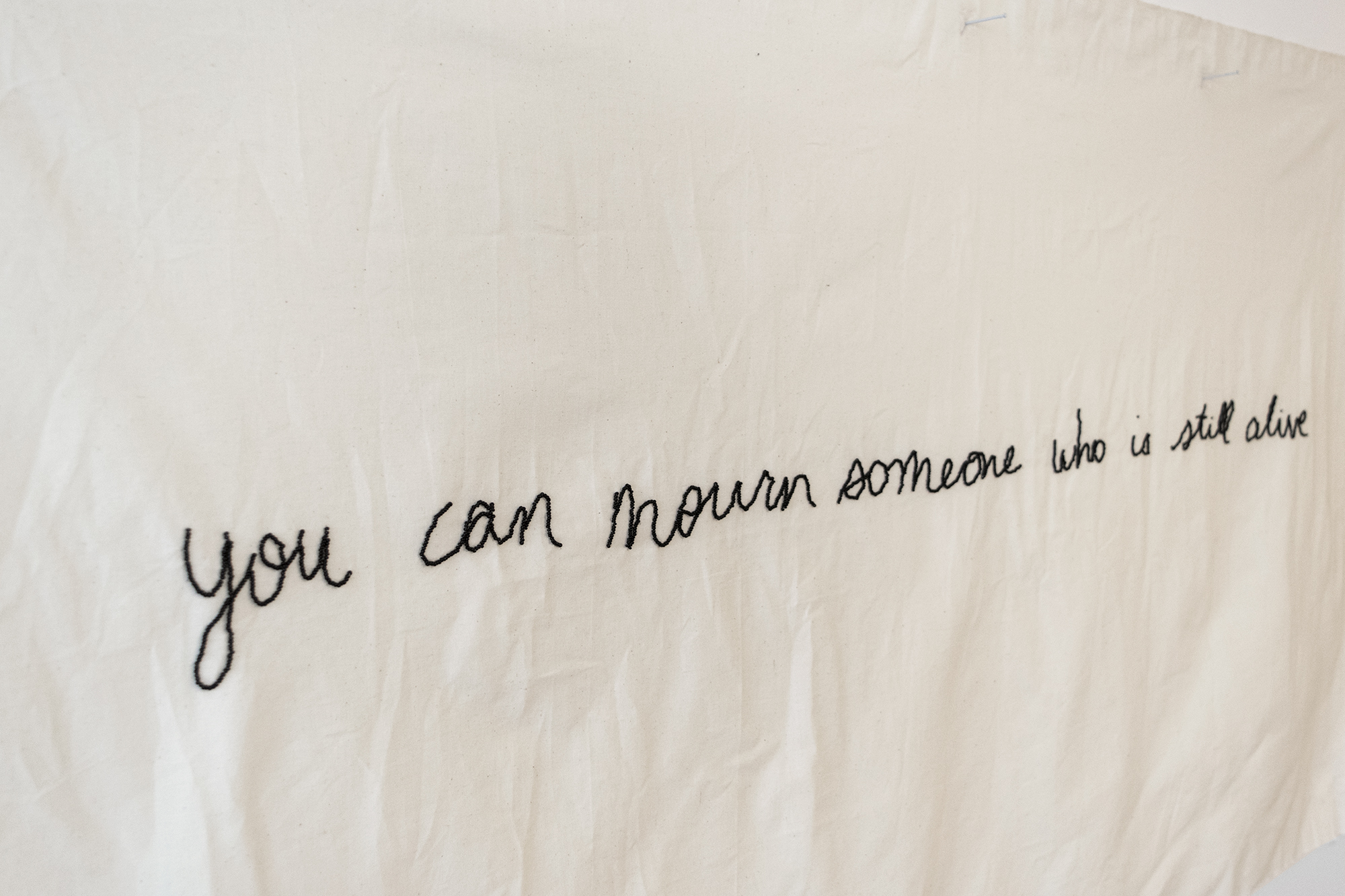

The New Gallery’s collection is a repository of materials dating from the founding of Clouds ‘n’ Water Gallery in 1975 that encompasses gallery activities, reference materials, artist correspondence, and exhibition ephemera. Over the course of our history, records have been retained and organized by an always-rotating, and always small, base of arts workers, leading to an archive that reflects the volatile fluctuations of artist run culture in both its contents and its methods of care.

Our collection may be useful for artistic or curatorial inspiration, and we encourage you to browse our material for ideas, provocations, and fruitful gaps, errors, or faults. Individual artist files may also be helpful for researchers interested in primary sources written or created by artists.

The New Gallery’s collection includes archival holdings, which encompasses our large artist and exhibition files, as well as other material, as well as our library, which contains a collection of books, magazines, and pamphlets.

Our collection documents the functions of our organization from 1975 to the present day, and continues to update with each exhibition. We are currently undergoing a digitization process, making selected exhibition materials and born-digital exhibition material content available online. Other born-digital material is being retained on our google drive archive.

If you are searching for a specific artist or show, please browse our search terms above. To learn more about our archival collection, please consult our finding aids. If you would like to request to view material from our archive in person, or if you would like more information about part of our collection, don’t hesitate to contact a member of our staff.

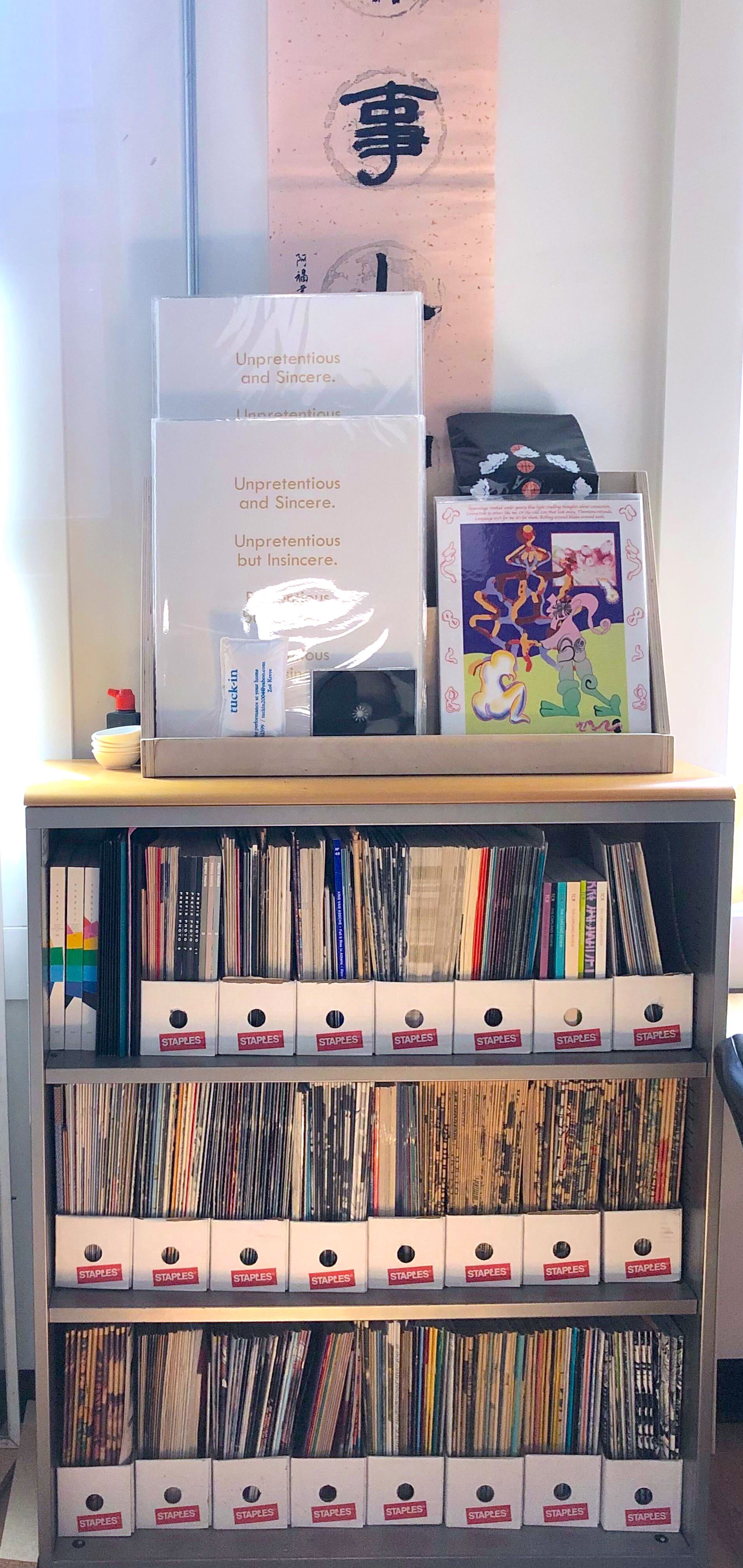

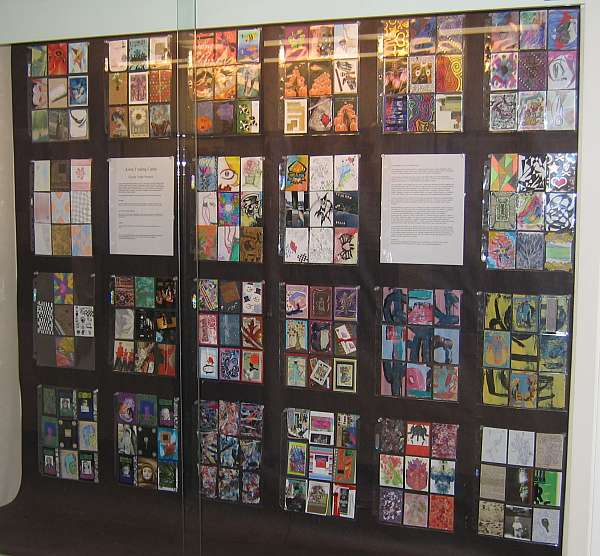

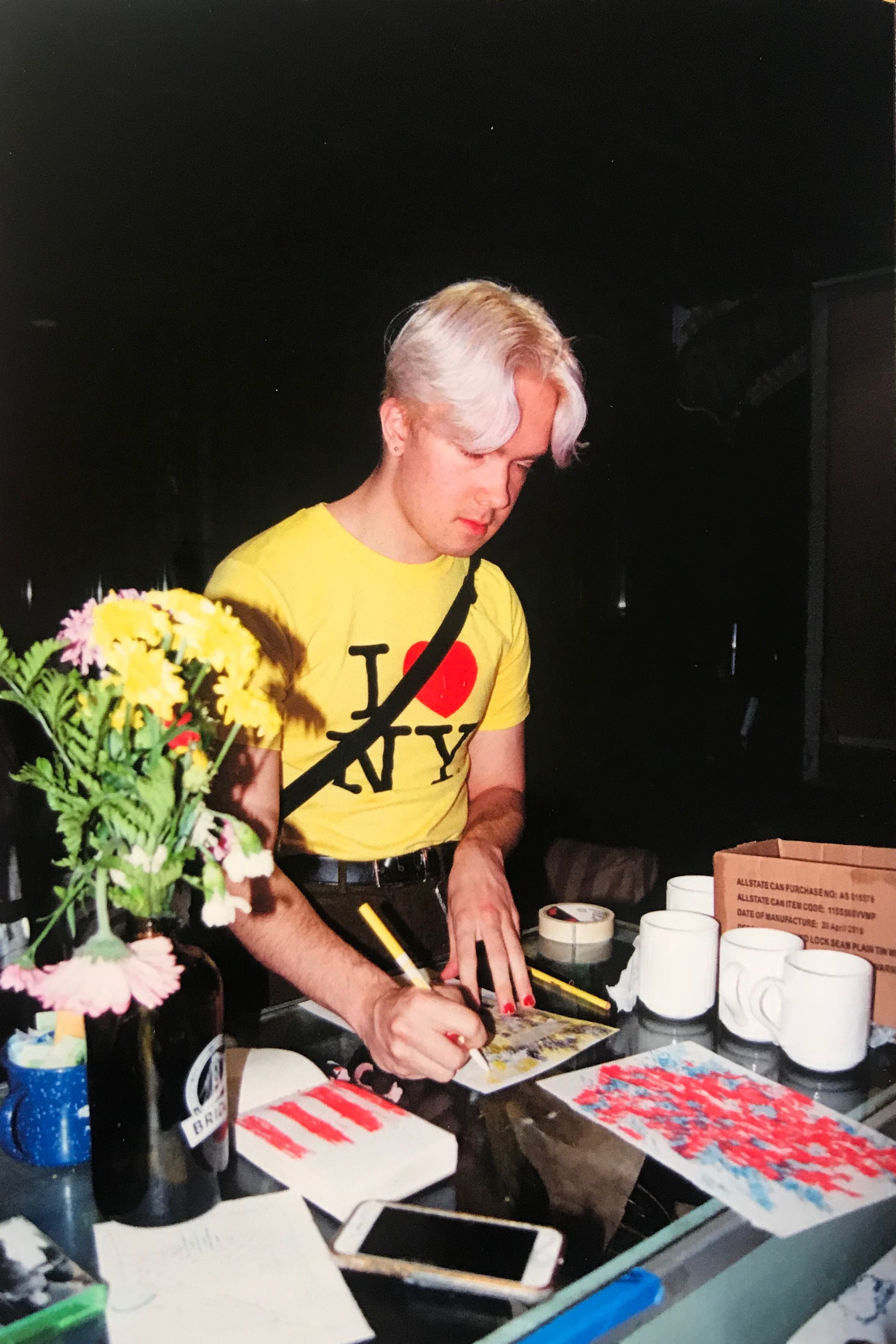

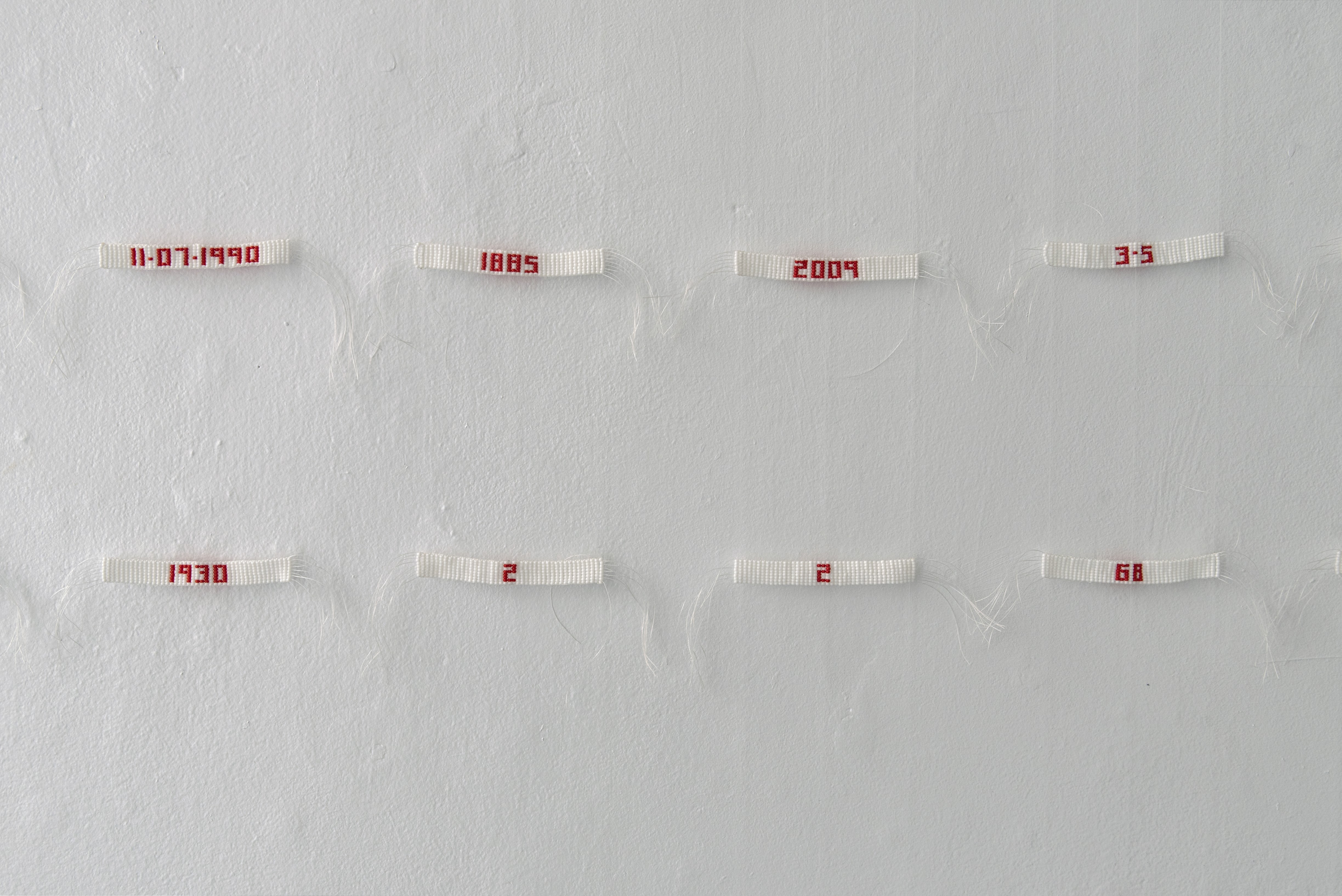

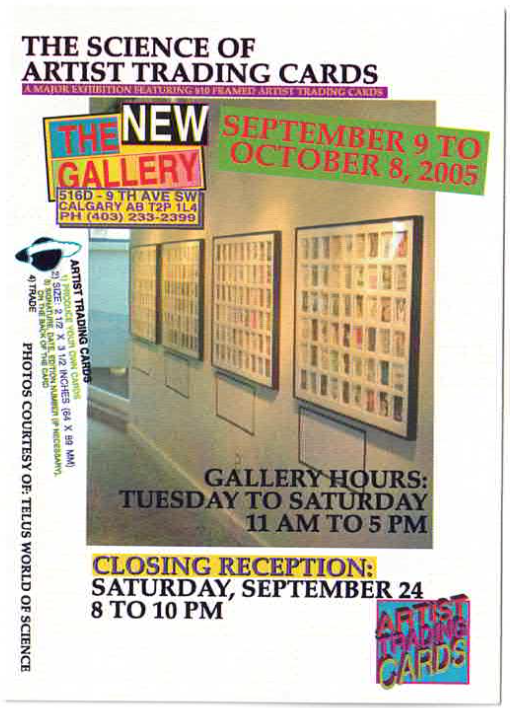

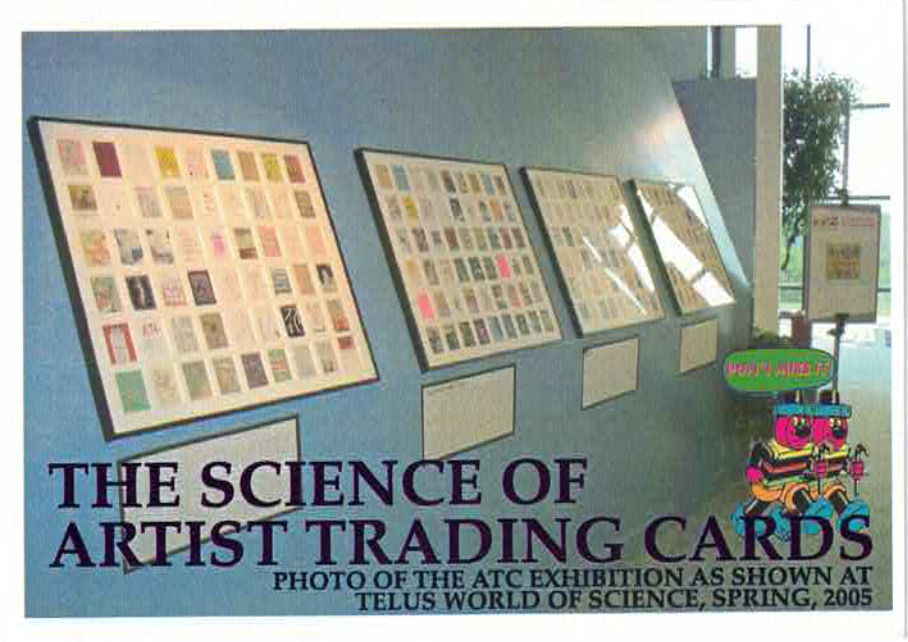

Artist Trading Cards

Artist Trading Cards (ATCs) are part of an effort to increase the public’s acceptance of art as an aspect of daily life, and to encourage artistic production not just consumption. ATCs encourage Calgarians, regardless of background, to become active in the local arts community. TNG began supporting ATCs in 1997 and used to support its activities by hosting Trading Card Sessions on the last Saturday of each month from 5:00 – 7:00 PM and by promoting ATCs provincially, with a touring ATC exhibition and workshop program through The Alberta Society of Artists (ASA) as part of Alberta Foundation of the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program (AFATEP).

ATCs are miniature works of art, created on 2.5 x 3.5 inch card stock. There are no restrictions as to medium (they run the gamut from painting to collage to rubberstamps to found images to the limits of your imagination), subject matter or number; they may be 2D or 3D, original, a series, an edition or a multiple.

Regular Trading Sessions were held on the last Saturday of every month from 5:00 to 7:00 PM at The New Gallery. Whatever your age or art background, you were invited to attend the Trading Sessions. (Observe for the first time if you like, but we guarantee you will be making your own cards soon after!)

History

The concept of Artist Trading Cards (ATC) was initiated by Zürich artist m. vänçi stirnemann and developed/promoted by himself and artist Cat Schick through INK.art&text in Zürich. In September 1997 Don Mabie (a.k.a. Chuck Stake) brought the first ATC session to Calgary at The New Gallery. Since that time regular Trading Sessions have been held every month. As many as 75 individuals have attended the monthly trading sessions with a core group of 30-35 people in regular attendance. The participants include artists, art students and members of the general public ranging from six to sixty years of age. The democratic and free exchange involved in trading these cards creates a space for the production of a vernacular art form outside of the hierarchical high-art world. In addition to the in-person trading sessions where artists meet to discuss and trade works the phenomena of ATCs continues to spread across the globe through trades via mail.

ATC Committee

Previously a Committee of The New Gallery, Artist Trading Cards Calgary is now an independent team and the organizing group which keeps ATCs going in Calgary and aids in growth of the ATC movement world wide. The official members of the committee were Paul Brown, Theo Nelson, June Hills, and now also Eija Koskinen, Kira Fowell. Honorary members are Chuck Stake (aka Don Mabie), Melody Nayler Keller, and Georgie Stone.

Links

http://www.artisttradingcards.org/

Follow Artist Trading Cards Calgary on instagram: @atccalgary

& use the hashtag #atcyyc

Archive

The New Gallery’s Resource Centre (208 Centre St. SE, upstairs) holds our Artist Trading Cards archive. Included in the collection are ATC event posters from 1998-2001, administrative files relating to ATC events and the ATC committee, programming materials from ATC events held at TNG, and TNG’s own collection of 225 ATCs. To view the collection or request more information, please contact our team.

Archive / By Artist or Curator Surname

#

2Bears, Jackson- A.100

A

Abel, Michael -G.100

Abeleva, Olga

Abson, Jill -G.113

Action Hero

Action Terroriste Socialement Acceptable (ATSA)

Adams, Adrienne -A.101, G.263

Adler, Dan

Adrian, Robert -A.102

Aebi, Iréne -A.422

Al-Issa, Asmaa -A.394

Alberta Now (EAG) -G.105

Albrecht, Hans -G.114

Alfon, Alden -G.278

Alexander, Maddie -A102.5

Alkalay, Andrea

Allard, Pierre -G.104

Allen, Wendy -A.103

Allikas, Barry -A.104

Allison, Carrie

Alvarado, Dan

Amantea, Gisele -A.105

Ambivalently Yours -A.440

Amir, Sefi -A.106

Amos, Barbara -G.110, G.247

Anderson, Colleen -A.107

Anderson, Jack -A.108, G.123, G.135, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Anderson, Joseph -A.109

Anderson, Randy -A.110

Andresen, Kim -A.111

Anzola, Laura

Arberry, Dan -A.112

Archinuk, Tracy -G.303

Armitage-Ferguson, Stephanie -A.113

Armstrong, Leila -A.114

Armstrong, Neil -A.115

Arnott, Ryan - A.115.100

Arroyo, Victor

Art Tour Detour -G.115

asinnajaq

Askren, Patricia - G.114.100, G.124.100, G.215

Attoe, Karen

Authier, Melanie -A.116

Aust, Konrad

Ayling, Carl -A.117, G.149

Azad, Madeleine - A.117.100, G.114.100

Aziz, Sylvat -A.118, A.118.1, G.103

Abeleva, Olga

Abson, Jill -G.113

Action Hero

Action Terroriste Socialement Acceptable (ATSA)

Adams, Adrienne -A.101, G.263

Adler, Dan

Adrian, Robert -A.102

Aebi, Iréne -A.422

Al-Issa, Asmaa -A.394

Alberta Now (EAG) -G.105

Albrecht, Hans -G.114

Alfon, Alden -G.278

Alexander, Maddie -A102.5

Alkalay, Andrea

Allard, Pierre -G.104

Allen, Wendy -A.103

Allikas, Barry -A.104

Allison, Carrie

Alvarado, Dan

Amantea, Gisele -A.105

Ambivalently Yours -A.440

Amir, Sefi -A.106

Amos, Barbara -G.110, G.247

Anderson, Colleen -A.107

Anderson, Jack -A.108, G.123, G.135, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Anderson, Joseph -A.109

Anderson, Randy -A.110

Andresen, Kim -A.111

Anzola, Laura

Arberry, Dan -A.112

Archinuk, Tracy -G.303

Armitage-Ferguson, Stephanie -A.113

Armstrong, Leila -A.114

Armstrong, Neil -A.115

Arnott, Ryan - A.115.100

Arroyo, Victor

Art Tour Detour -G.115

asinnajaq

Askren, Patricia - G.114.100, G.124.100, G.215

Attoe, Karen

Authier, Melanie -A.116

Aust, Konrad

Ayling, Carl -A.117, G.149

Azad, Madeleine - A.117.100, G.114.100

Aziz, Sylvat -A.118, A.118.1, G.103

B

Baars, Ab

Bachmann, Ingrid -A.119

Baczynski Ryan & Smith -A.120

Badrin, Omar -A.122

Baigent, Jane -G.244, G.244.1

Baily, Derek -A.121

Baker, Cindy -A.124, G.193, G.200, G.256.100

Baker, Griffith Aaron -A.123

Bakker, Conrad -G.256

Balcaen, Jo-Anne -A.124.100

Balfour, Barbara McGill -A.125

Balz, Suzan Dionne -G.130

Bampton, Brooke -A.127, G.149

Banana, Anna -A.126, G.187, G.257.2, G.304

Bandura, Phillip -A.128

Bankey, Miriam -A.129

Bannerman, James -A.130

Bannerman, Maja -A.131

Barbáchano, Pedro -A.132.5

Barbier, Sally -A.133, A.134, G.204.100

Barbour, Dave -G.234.100

Bareham, Dean -G.171

Baril, Celine -A.135

Barker, Charlotte - A.135.100

Barnson, Kathy -A.136

Bartholomew, Sophia -A.137

Bartol, Alana -A.138

Barua, Kiki -G.291

Battle, Christina

Baxter, Iain -G.198, G.238, G.311

Baylon, Jordan

Beal, Kyle

Beam, Robert -A.139

Beauchamps, Ron -A.139.100

beaulieu, derek -A.140, G.267

Beck, Sarah -G.290

Beckly, Steven -A.141

Beef, Joe (Michael Haslam) -A.142

Belanger, Erin -G.291

Belcourt, David -A.143

Bell, Wade -G.172

Bellas, Benjamin -A.141

Belliveau, Elisabeth -A.144

Bender, Arnold -G.106

Benesiinaabandan, Scott

Bennett, Brent - G.124.100, G.234.300

Bennett, Rick -G.234.100

benni

Berg, Eddie -A.145

Berg, Nowell -A.145.100

Berquist, Douglas -A.145.100

Berry, Melissa -G.291

Berscheid, Helen -A.146

Besant, Derek

Bessette, Myriam -G.129.100

Bethune-Leamen, Katie

Bewley, Jon -A.147

Bickel, Barbara -A.148

Biebrich, Tamara Rae -G.265

Biedak, Louis -G.108

Bienvenue, Marcella -A.149, G.148, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.224, G.224.1

Bierk, David -G.113

Bigras-Burrogano, Frederic

Bill

Bilsen, Joke Van -A.665

Binder-Ouellette, Alison -G.130

Birhanu, Eva

Birnie, Colin -A.150

Birse, Ian -A.151, G.149, G.211

Bishop, James -A.152

Black, Anthea -G.193

Black, Byron -A.153

Black, Lascelles -A.154, G.310

Black, Liam

Blackwell, Adrian -A.155, G.208.200

Blanchard, Sam -A.156

Blatherwick, David -A.157

Blom, Monique -A.158

Bloom, Tony -G.124.50

Blouin, René -A.159

Blyth, Michael -A.160

Boisvert, Cynthia -G.198

Bök, Christian

Bond, Eleanor -A.161, G.207, G.301

Bondaroff, Carole -G.101, G.114.100, G.120

Borch, Gerald -A.162

Bote, Tivadar -G.118

Bouabane, Kotama

Bourgault, Rébecca -G.244, G.244.1

Bowers, Harry - G.234.200

Boyne, Chris -A.163

Boyle, Hannah -G.117

Boyle, John -G.113

Bozic, Susan -A.164

Bozdarov, Atanas -A.163.5

bp, Nichol -A.540

Brace, Brad -A.165

Bradley, Maureen - G.158

Brady, Lee -G.174.200

Brant, Jennifer

Brawley, Dawn -G.118

Brawn, Lisa -A.166

Brdar, Nick -A.167

Brennan, Blair

Brent, Rodney “Guitarsplat” - G.149

Bresnahan, Keith

Bristol, Joanne -G.256.100

Brodie, Jim -G.124.100, G.145.100

Brookes, Chris -A.168

Brouwers, Stephen -A.169

Brown, Caitlind -G.291, G.292

Brown, Collin

Brown, Dennis -A.170

Brown, Janet -G.303.100

Brownoff, Alan -A.171

Bruckner, Gary -G.106

Bruneau, Serge -G.113

Brunel, Cookie

Brunel, Nicole

Buckland, Michael -A.172

Buchanan, Heather -G.100

Bucknell, Lea

Budsberg, Brent -G.309

Buis, Doug -A.173

Bunnell, Alexa

Bureau, Patrick L. -G.102

Burger, Steve -A.174, G.216

Burisch, Nicole -G.193

Burnett, Murdoch -A.175, G.103

Burns, Kay -A.176, G.278

Burroughs, William S. -A.177

Busby, Billie Ray -G.253.100

Bush, Dana -G.253.100

Butler, Jack

Butler, Sheila -A.178, G.207, G.302

Butters, Thomas J

Byrne, Peter -A.179

Bachmann, Ingrid -A.119

Baczynski Ryan & Smith -A.120

Badrin, Omar -A.122

Baigent, Jane -G.244, G.244.1

Baily, Derek -A.121

Baker, Cindy -A.124, G.193, G.200, G.256.100

Baker, Griffith Aaron -A.123

Bakker, Conrad -G.256

Balcaen, Jo-Anne -A.124.100

Balfour, Barbara McGill -A.125

Balz, Suzan Dionne -G.130

Bampton, Brooke -A.127, G.149

Banana, Anna -A.126, G.187, G.257.2, G.304

Bandura, Phillip -A.128

Bankey, Miriam -A.129

Bannerman, James -A.130

Bannerman, Maja -A.131

Barbáchano, Pedro -A.132.5

Barbier, Sally -A.133, A.134, G.204.100

Barbour, Dave -G.234.100

Bareham, Dean -G.171

Baril, Celine -A.135

Barker, Charlotte - A.135.100

Barnson, Kathy -A.136

Bartholomew, Sophia -A.137

Bartol, Alana -A.138

Barua, Kiki -G.291

Battle, Christina

Baxter, Iain -G.198, G.238, G.311

Baylon, Jordan

Beal, Kyle

Beam, Robert -A.139

Beauchamps, Ron -A.139.100

beaulieu, derek -A.140, G.267

Beck, Sarah -G.290

Beckly, Steven -A.141

Beef, Joe (Michael Haslam) -A.142

Belanger, Erin -G.291

Belcourt, David -A.143

Bell, Wade -G.172

Bellas, Benjamin -A.141

Belliveau, Elisabeth -A.144

Bender, Arnold -G.106

Benesiinaabandan, Scott

Bennett, Brent - G.124.100, G.234.300

Bennett, Rick -G.234.100

benni

Berg, Eddie -A.145

Berg, Nowell -A.145.100

Berquist, Douglas -A.145.100

Berry, Melissa -G.291

Berscheid, Helen -A.146

Besant, Derek

Bessette, Myriam -G.129.100

Bethune-Leamen, Katie

Bewley, Jon -A.147

Bickel, Barbara -A.148

Biebrich, Tamara Rae -G.265

Biedak, Louis -G.108

Bienvenue, Marcella -A.149, G.148, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.224, G.224.1

Bierk, David -G.113

Bigras-Burrogano, Frederic

Bill

Bilsen, Joke Van -A.665

Binder-Ouellette, Alison -G.130

Birhanu, Eva

Birnie, Colin -A.150

Birse, Ian -A.151, G.149, G.211

Bishop, James -A.152

Black, Anthea -G.193

Black, Byron -A.153

Black, Lascelles -A.154, G.310

Black, Liam

Blackwell, Adrian -A.155, G.208.200

Blanchard, Sam -A.156

Blatherwick, David -A.157

Blom, Monique -A.158

Bloom, Tony -G.124.50

Blouin, René -A.159

Blyth, Michael -A.160

Boisvert, Cynthia -G.198

Bök, Christian

Bond, Eleanor -A.161, G.207, G.301

Bondaroff, Carole -G.101, G.114.100, G.120

Borch, Gerald -A.162

Bote, Tivadar -G.118

Bouabane, Kotama

Bourgault, Rébecca -G.244, G.244.1

Bowers, Harry - G.234.200

Boyne, Chris -A.163

Boyle, Hannah -G.117

Boyle, John -G.113

Bozic, Susan -A.164

Bozdarov, Atanas -A.163.5

bp, Nichol -A.540

Brace, Brad -A.165

Bradley, Maureen - G.158

Brady, Lee -G.174.200

Brant, Jennifer

Brawley, Dawn -G.118

Brawn, Lisa -A.166

Brdar, Nick -A.167

Brennan, Blair

Brent, Rodney “Guitarsplat” - G.149

Bresnahan, Keith

Bristol, Joanne -G.256.100

Brodie, Jim -G.124.100, G.145.100

Brookes, Chris -A.168

Brouwers, Stephen -A.169

Brown, Caitlind -G.291, G.292

Brown, Collin

Brown, Dennis -A.170

Brown, Janet -G.303.100

Brownoff, Alan -A.171

Bruckner, Gary -G.106

Bruneau, Serge -G.113

Brunel, Cookie

Brunel, Nicole

Buckland, Michael -A.172

Buchanan, Heather -G.100

Bucknell, Lea

Budsberg, Brent -G.309

Buis, Doug -A.173

Bunnell, Alexa

Bureau, Patrick L. -G.102

Burger, Steve -A.174, G.216

Burisch, Nicole -G.193

Burnett, Murdoch -A.175, G.103

Burns, Kay -A.176, G.278

Burroughs, William S. -A.177

Busby, Billie Ray -G.253.100

Bush, Dana -G.253.100

Butler, Jack

Butler, Sheila -A.178, G.207, G.302

Butters, Thomas J

Byrne, Peter -A.179

Cabri, Louis

Cairns, Cassie - G.123.200

Caldwell, Alex -G.240

Caldwell, Molly JF -A.179.100

Calgary Chinese Community Service Association (CCCSA)

Campbell, Blaine

Campbell, Carol -A.474, G.129

Campbell, Colleen -G.124.100

Campbell, Kasie -A.179.15

Campbell, Michael -A.180, A.181, G.256

Campbell, Tim -G.145, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.239, G.286, G.303

Canadien, Bruno -A.182

Capune, Simone -G.117

Cardiff, Janet -A.183, G.190

Cardinal-Schubert, Joane -A.183.100, G.103, G.160, G.197, G.280

Carlos, Marbella -G.292

Carlson, William

Caron, Quentin -A.105, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Carrión, Ulises -A.184, G.159

Carson, Bob -A.262

Carte, Suzanne

Carter, Kent -A.422

Carwadine, Mary -G.118

Casey, Dave -A.185, G.194

Cassells, Laara -A.186

Castrée, Genevieve -A.187

Caulfield, Sean -A.188

Celli, Joseph -A.189

Center for Tactical Magic -G.256

Centofanti, Melissa -A.190

Century, Michael -A.190.100

Chadbourne, Eugene -A.191, G.255

Chalke, John -A.658, G.204.100, G.257, G.257.1

Chambers, Jonathon -G.106

Chan, Ed -G.109

Chan, Stephen

Charles, Jayden

Charron, Robert -A.192

Charzewski, Jarod -A.193

Chaykowski, Natasha

Che, Kaili

Chellas, Merry -A.194

Cheney, David -A.195, G.240

Cheng, Qian

Cherniavsky, Pippa -A.196, G.186

Cheta, Bogdan

Cheung, Christine -A.197

Cheung, Joni “Snack-Witch” -G. 168.05

Cheung, Raeann Kit-Yee -G.315.5

Chitty, Elizabeth - G.300

Cho, Diana Un-Jin -A.198

Chordalone, Max -A.199

Christiansen, Cam -A.200

Christianson, Shirley - A.225.100

Christopher, Gordon -A.474, G.129

Chu, Josie -A.201, G.156, G.257, G.257.1

Clamp, Alannah -G.146

Clark, David -A.202, A.203.1

Clark, Elizabeth -A.203, G.118, G.119, G.257, G.257.1

Clark, Joe -A.204

Clark, Robert -A.204.100

Clarke, Michèle Pearson -A.204.15

Claxton, Dana

Clément, Jacques -A.205

Clintberg, Mark -G.278

Clover Living -G.315.5

Coleman, Victor -A.207, G.182

Coles, Maury -A.476

Colín, Carlos -A.207.5

Commanda, Marcel -G.245, G.245.1

Connor, Linda - G.234.200

Connolly, Brian -A.208

Connolly, R.P. -A.209

Conway, Jenny -A.210

Cook, Christine -G.171, G.221

Cook, Jo -A.211

Cooley, Alison

Coolidge, Michael

Corless, Marianne -A.212

Corry, Corrine -A.213

Cottingham, Steven

Coultas, Stella -G.124.100

Cousins, Charles (C.K.) -A.214, G.106, G.190, G.257, G.257.1

Coutts-Smith, Kenneth -A.215, G.112

Craig, Ken -A.216, G.134, G.194

Cram, Paul -A.216.100, G.191

Cran, Chris - A.216.200, G.163, G.198

Creighton-Kelly, Chris -A.217, G.103, G.160

Crespin, Augusto -G.245, G.245.1

Crighton, Jennifer

Crispin, Sterling

Crop Eared Wolf, Marjie -A.219

Crozier, Lorna (Uher) -A.220

Curnoe, Greg -G.113

Curry, Derek

Cuthland, Ruth -A.275

Curtis, David -A.221, G.198

Curwin, Will -A.222

Curzon, Daniel -A.223

Cairns, Cassie - G.123.200

Caldwell, Alex -G.240

Caldwell, Molly JF -A.179.100

Calgary Chinese Community Service Association (CCCSA)

Campbell, Blaine

Campbell, Carol -A.474, G.129

Campbell, Colleen -G.124.100

Campbell, Kasie -A.179.15

Campbell, Michael -A.180, A.181, G.256

Campbell, Tim -G.145, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.239, G.286, G.303

Canadien, Bruno -A.182

Capune, Simone -G.117

Cardiff, Janet -A.183, G.190

Cardinal-Schubert, Joane -A.183.100, G.103, G.160, G.197, G.280

Carlos, Marbella -G.292

Carlson, William

Caron, Quentin -A.105, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Carrión, Ulises -A.184, G.159

Carson, Bob -A.262

Carte, Suzanne

Carter, Kent -A.422

Carwadine, Mary -G.118

Casey, Dave -A.185, G.194

Cassells, Laara -A.186

Castrée, Genevieve -A.187

Caulfield, Sean -A.188

Celli, Joseph -A.189

Center for Tactical Magic -G.256

Centofanti, Melissa -A.190

Century, Michael -A.190.100

Chadbourne, Eugene -A.191, G.255

Chalke, John -A.658, G.204.100, G.257, G.257.1

Chambers, Jonathon -G.106

Chan, Ed -G.109

Chan, Stephen

Charles, Jayden

Charron, Robert -A.192

Charzewski, Jarod -A.193

Chaykowski, Natasha

Che, Kaili

Chellas, Merry -A.194

Cheney, David -A.195, G.240

Cheng, Qian

Cherniavsky, Pippa -A.196, G.186

Cheta, Bogdan

Cheung, Christine -A.197

Cheung, Joni “Snack-Witch” -G. 168.05

Cheung, Raeann Kit-Yee -G.315.5

Chitty, Elizabeth - G.300

Cho, Diana Un-Jin -A.198

Chordalone, Max -A.199

Christiansen, Cam -A.200

Christianson, Shirley - A.225.100

Christopher, Gordon -A.474, G.129

Chu, Josie -A.201, G.156, G.257, G.257.1

Clamp, Alannah -G.146

Clark, David -A.202, A.203.1

Clark, Elizabeth -A.203, G.118, G.119, G.257, G.257.1

Clark, Joe -A.204

Clark, Robert -A.204.100

Clarke, Michèle Pearson -A.204.15

Claxton, Dana

Clément, Jacques -A.205

Clintberg, Mark -G.278

Clover Living -G.315.5

Coleman, Victor -A.207, G.182

Coles, Maury -A.476

Colín, Carlos -A.207.5

Commanda, Marcel -G.245, G.245.1

Connor, Linda - G.234.200

Connolly, Brian -A.208

Connolly, R.P. -A.209

Conway, Jenny -A.210

Cook, Christine -G.171, G.221

Cook, Jo -A.211

Cooley, Alison

Coolidge, Michael

Corless, Marianne -A.212

Corry, Corrine -A.213

Cottingham, Steven

Coultas, Stella -G.124.100

Cousins, Charles (C.K.) -A.214, G.106, G.190, G.257, G.257.1

Coutts-Smith, Kenneth -A.215, G.112

Craig, Ken -A.216, G.134, G.194

Cram, Paul -A.216.100, G.191

Cran, Chris - A.216.200, G.163, G.198

Creighton-Kelly, Chris -A.217, G.103, G.160

Crespin, Augusto -G.245, G.245.1

Crighton, Jennifer

Crispin, Sterling

Crop Eared Wolf, Marjie -A.219

Crozier, Lorna (Uher) -A.220

Curnoe, Greg -G.113

Curry, Derek

Cuthland, Ruth -A.275

Curtis, David -A.221, G.198

Curwin, Will -A.222

Curzon, Daniel -A.223

D

Dajczer, Brigitte -A.224, G.263

Dalziel, Frank - A.224.100, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100

Dancers’ Studio West

Dang, Qui Dac -G.124.100

Danker, Carl -G.120

David, Paul -G.106

Davidson, Sarah

Davis, Judy -A.225, A.225.100, G.101, G.216

Davis, Karrie -A.226

Day, Kevin

Deacon, Peter -A227

Dean, John -G.215, G.257, G.257.1, G.303.100

Decker, Ken -A228, A288.100

DeHaan, Jason -A.229

Delage, Guy -A.229.100

Delve, Ryan

Demchuk, Kristin -A.230

Demkiw, Janis -A.231

Dempsey, Shawna -A.232, G.199, G.265

Demuth, Michel -A.233, G.160

Dennett, Derek

Dennis, Danièle -A.234

Dennis, Sheila -A.235

Dennison, Noland -A.236, G.234

Denoon, Amber -A.237, G.257, G.257.1

DesChene, Wendy -G.212

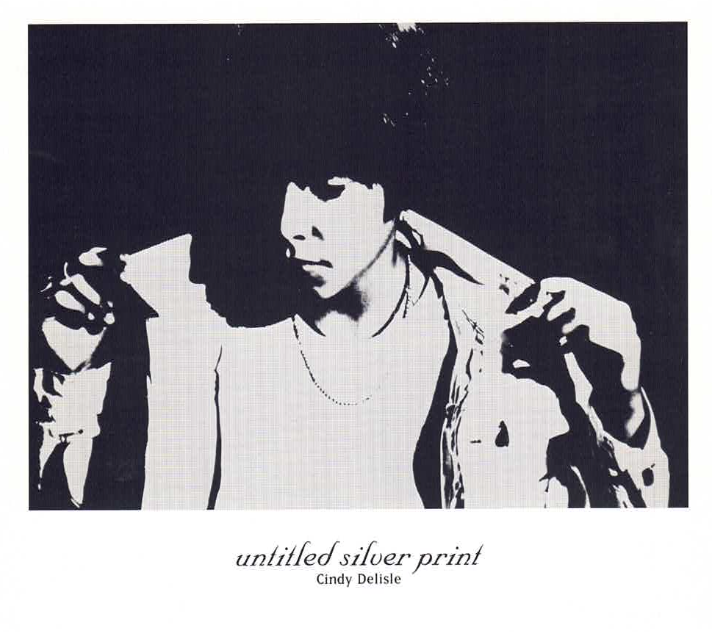

Deslile, Cindy

De Souza, Shyra -A.238

Diamond, Dallas -A.239

Dicey, Mark -A.240, G.106, G.107, G.118, G.119, G.122, G.134, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.174.100, G.187, G.214.100, G.218.100, G.226, G.232, G.238,

G.257, G.257.1, G.306, G.307

Dickson, Jennifer -G.113

Diduch, Luba -A.241

Diep, Vi An -G.149, G.263

Dierdorff, Brooks -A.139, A.242

Doerksen, Hannah -G.100

Donahue, Mary -G.244, G.244.1

Dong, Chun Hua Catherine -A.243

Dong, Qui Dac - G.114.100

Dong, Yuxiang -G.271.100

Donoghue, Lynn -G.113

Doremus, Ernest - G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50

Dorrer, Angela - A.244

Doucet, Hannah -A.245

Doyle, Dan (sam d.d. iiguana) -A.246

Doyle, Keith H. -A.246.100, G.181

Dragan, Miruna

Dragojevic, Vuk

Dragu, Margaret -A.247

Drummond, Jeremy -A.248

Duchesne, Corrine -A.253

Dueck, Jonathan -A.249

Duff, Tagny -A.250

Dufour, Garry -A.251

Dufresne, Leah -G.118

Dufresne, Martin

Dugas, Daniel -G.304.100

Dunning, Alan -A.252, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.176, G.239, G.257, G.257.1, G.273, G.274

Dupuis, Robin -G.129.100

Dutton, Paul

Dalziel, Frank - A.224.100, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100

Dancers’ Studio West

Dang, Qui Dac -G.124.100

Danker, Carl -G.120

David, Paul -G.106

Davidson, Sarah

Davis, Judy -A.225, A.225.100, G.101, G.216

Davis, Karrie -A.226

Day, Kevin

Deacon, Peter -A227

Dean, John -G.215, G.257, G.257.1, G.303.100

Decker, Ken -A228, A288.100

DeHaan, Jason -A.229

Delage, Guy -A.229.100

Delve, Ryan

Demchuk, Kristin -A.230

Demkiw, Janis -A.231

Dempsey, Shawna -A.232, G.199, G.265

Demuth, Michel -A.233, G.160

Dennett, Derek

Dennis, Danièle -A.234

Dennis, Sheila -A.235

Dennison, Noland -A.236, G.234

Denoon, Amber -A.237, G.257, G.257.1

DesChene, Wendy -G.212

Deslile, Cindy

De Souza, Shyra -A.238

Diamond, Dallas -A.239

Dicey, Mark -A.240, G.106, G.107, G.118, G.119, G.122, G.134, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.174.100, G.187, G.214.100, G.218.100, G.226, G.232, G.238,

G.257, G.257.1, G.306, G.307

Dickson, Jennifer -G.113

Diduch, Luba -A.241

Diep, Vi An -G.149, G.263

Dierdorff, Brooks -A.139, A.242

Doerksen, Hannah -G.100

Donahue, Mary -G.244, G.244.1

Dong, Chun Hua Catherine -A.243

Dong, Qui Dac - G.114.100

Dong, Yuxiang -G.271.100

Donoghue, Lynn -G.113

Doremus, Ernest - G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50

Dorrer, Angela - A.244

Doucet, Hannah -A.245

Doyle, Dan (sam d.d. iiguana) -A.246

Doyle, Keith H. -A.246.100, G.181

Dragan, Miruna

Dragojevic, Vuk

Dragu, Margaret -A.247

Drummond, Jeremy -A.248

Duchesne, Corrine -A.253

Dueck, Jonathan -A.249

Duff, Tagny -A.250

Dufour, Garry -A.251

Dufresne, Leah -G.118

Dufresne, Martin

Dugas, Daniel -G.304.100

Dunning, Alan -A.252, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.176, G.239, G.257, G.257.1, G.273, G.274

Dupuis, Robin -G.129.100

Dutton, Paul

E

Edgar, Linda -A.254, G.124.50

Edmonson, Greg

Edmundson, Grier-A.255

Edwards, Richard - G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.216

Eggermont, Marjan -A.256, G.120

Ehrenworth, Daniel -A.106, A.257

Eigenkind, Heidi -G.265

Eisen, Johnnie -A.258

Eisler, John -A.259, G.230

Elder, Bruce -G.113

Eliot, Elyse -A.260, A.261

Ellis, Alyssa

Ellis, Lyle -A.476, A.216.100

Ellison, Coby -G.256

Ely, Roger -A.262, G.204

Enns, Maureen -A.262.100

Erban, Daniel -A.263, G.186

Erfanian, Eshrat -A.264

Escribano, Mark -G.309

Esguerra, Marilou

Espinoza, Nery -G.245, G.245.1

Esteban, Jason -A265

Eurich, Liza

Evans, Daniel -A266

Evans, Jane -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.241

Ewasiuk, Jennifer

Edmonson, Greg

Edmundson, Grier-A.255

Edwards, Richard - G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.216

Eggermont, Marjan -A.256, G.120

Ehrenworth, Daniel -A.106, A.257

Eigenkind, Heidi -G.265

Eisen, Johnnie -A.258

Eisler, John -A.259, G.230

Elder, Bruce -G.113

Eliot, Elyse -A.260, A.261

Ellis, Alyssa

Ellis, Lyle -A.476, A.216.100

Ellison, Coby -G.256

Ely, Roger -A.262, G.204

Enns, Maureen -A.262.100

Erban, Daniel -A.263, G.186

Erfanian, Eshrat -A.264

Escribano, Mark -G.309

Esguerra, Marilou

Espinoza, Nery -G.245, G.245.1

Esteban, Jason -A265

Eurich, Liza

Evans, Daniel -A266

Evans, Jane -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.241

Ewasiuk, Jennifer

F

Fabijan, Miriam -A.267

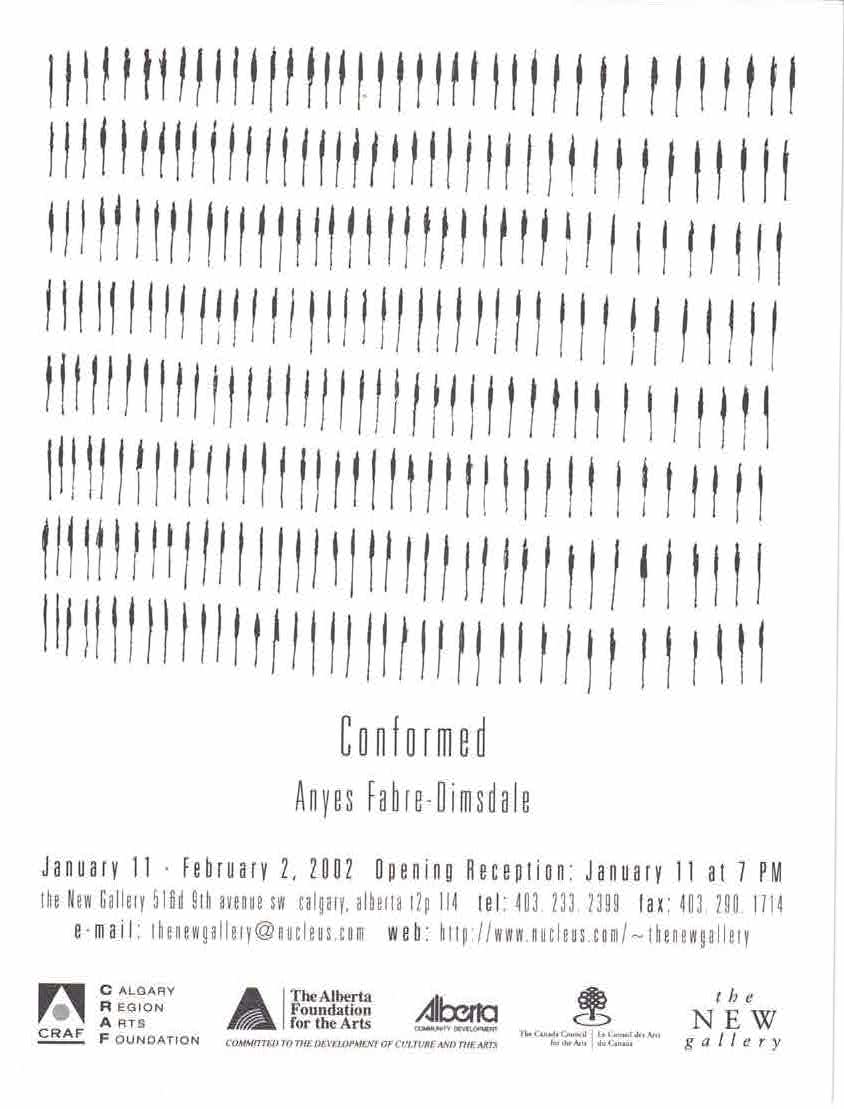

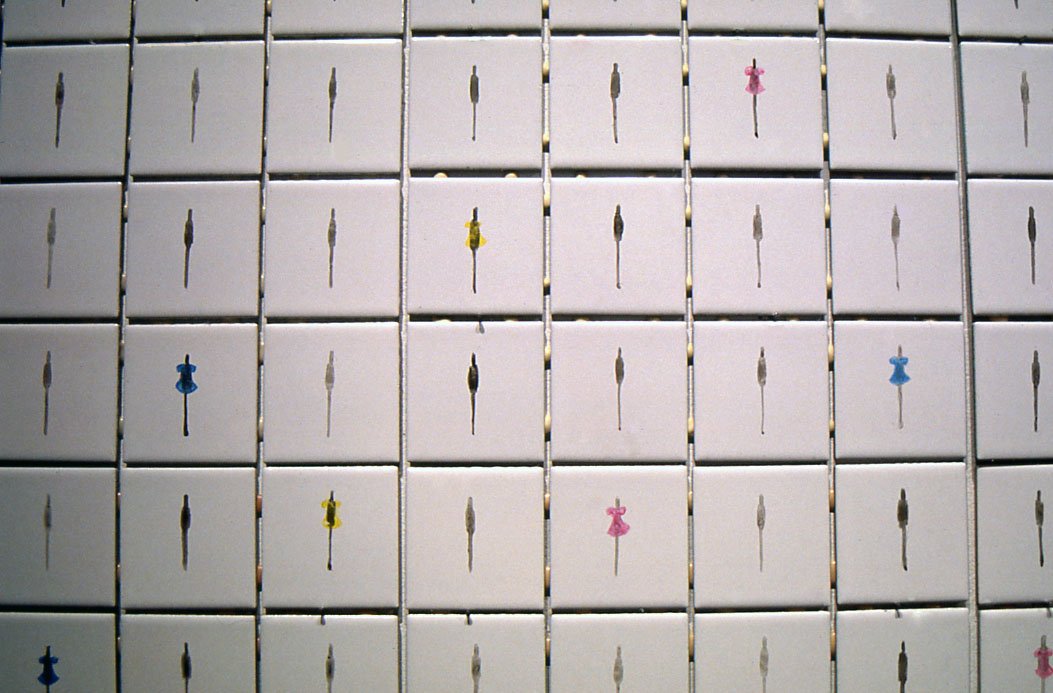

Fabre-Dimsdale, Anyes -A.268

Fagan, Christine -A.269, A.307

Faulkner, Norman -A.270, G.204.100, G.252, G.252.1

Fawcett, Brian -A.271

Fearon, Elizabeth -A.271

Feimo, Fung Ling -A.436.5

Ferguson, Gordon -A.273, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.205, G.205.1, G.257, G.257.1, G.307

Ferron -A.274

Festa, Angelika -A.275

Feucht, Johann - G.114.100

Fiegal, Murray -G.309.100

Filewych, Gordon - A.354.100

Filliou, Robert -A.276

Filman, Sonya -A.276.5

Fineday, Kylie -G.315.5

Finlayson, Lesley -A.277, G.253, G.286

Finney, Halie

Fisher, Kyra -A.278, G.118, G.119, G.252, G.252.1, G.253, G.286

FitzGerald, Pamma -G.291

Fitzpatrick, Jason W. Fowler -A.278.100

Fleck, Jillian -G.146

Florian, Mark -A.279

Flower, Chris -A.258

Flynn, Maggie

Forcade, Tim -A.290

Ford, Peter -G.117

Forkert, Kirsten

Forrest, Julian

Forster, Andrew -A.291, G.201

Fowler, Richard -A.281

Fowler, Skai -A.280

Fox, Charlie -A.282, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.215

Franceschini, Amy -G.256

Fraser, Joshua -G.253.100

Fraser, Joyce -A.283, G.134, G.176, G.251, G.314

Fredrickson, Denton

Freeman, Paul -A.284

Frenken, Susanne -G.114

Friedman, Ken -A.285

Friel, Chris -A.286

Friesen, Shaun -A.287

Friesen, Wayne -G.174.200

Frizzell, Jason E. -A.288

Frosst, Andrew

Frosst, John -A.289

Fuglem, Karilee -G.130

Fullerton, Brady -A.258.5

Fulmer, Mary-Jo -A.292

Fulton, Jack - G.234.200

Fabre-Dimsdale, Anyes -A.268

Fagan, Christine -A.269, A.307

Faulkner, Norman -A.270, G.204.100, G.252, G.252.1

Fawcett, Brian -A.271

Fearon, Elizabeth -A.271

Feimo, Fung Ling -A.436.5

Ferguson, Gordon -A.273, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.205, G.205.1, G.257, G.257.1, G.307

Ferron -A.274

Festa, Angelika -A.275

Feucht, Johann - G.114.100

Fiegal, Murray -G.309.100

Filewych, Gordon - A.354.100

Filliou, Robert -A.276

Filman, Sonya -A.276.5

Fineday, Kylie -G.315.5

Finlayson, Lesley -A.277, G.253, G.286

Finney, Halie

Fisher, Kyra -A.278, G.118, G.119, G.252, G.252.1, G.253, G.286

FitzGerald, Pamma -G.291

Fitzpatrick, Jason W. Fowler -A.278.100

Fleck, Jillian -G.146

Florian, Mark -A.279

Flower, Chris -A.258

Flynn, Maggie

Forcade, Tim -A.290

Ford, Peter -G.117

Forkert, Kirsten

Forrest, Julian

Forster, Andrew -A.291, G.201

Fowler, Richard -A.281

Fowler, Skai -A.280

Fox, Charlie -A.282, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.215

Franceschini, Amy -G.256

Fraser, Joshua -G.253.100

Fraser, Joyce -A.283, G.134, G.176, G.251, G.314

Fredrickson, Denton

Freeman, Paul -A.284

Frenken, Susanne -G.114

Friedman, Ken -A.285

Friel, Chris -A.286

Friesen, Shaun -A.287

Friesen, Wayne -G.174.200

Frizzell, Jason E. -A.288

Frosst, Andrew

Frosst, John -A.289

Fuglem, Karilee -G.130

Fullerton, Brady -A.258.5

Fulmer, Mary-Jo -A.292

Fulton, Jack - G.234.200

G

Gabor, Lana Ing -A.293

Gajda, Stefan -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Gallie, Tommy -G.124.50, G.214, G.214.1

Gammon, Lynda -A.293.100

Garcia, Sophie

Gardner-Popovac, Jasmine -A.294

Garlicki, Elizabeth -G.265

Garneau, David -A.295, G.109, G.149, G.234, G.242.100, G.278, G.279

Garrard, Rose -A.296

Garrett, Wayne

Gartley, Vera -A.297

Gaysek, Fred -A.298

Gerber, Natalie

Gerin, Annie -A.299

Gerz, Jochen -A.300

Geuer, Juan -A.301

Giammarino, Lorenzo -G.108.100

Giang, Paul -A.436.5

Gibson, Rick -A.302

Gibson, William -A.303

Gilbert, Gerry -A.304, G.182

Giles, Ken -A.305

Giles, Wayne - G.119, G.131, G.257, G.257.1, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Gillon, Annette -A.306

Gläser, Christine -G.114

Glenn, Allyson - A.269, A.307

Glenn, Mat

Godberson, Celine -G.158

Goertz, Jim -G.106

Gogal, Janice -G.117.100

Gogarty, Amy-A.308, G.117, G.244, G.244.1, G.257, G.257.1, G.261, G.266, G.277, G.278

Goldberg, Whoopi -A.309

Golden, Anne -G.158

Göllner, Adrian -A.310

Gooden, Tom - G.123.200

Goreas, Lee -A.311

Gorris, Susan -G.117.100

Gosselin, Marcel -A.312, G.299

Gossen, Cecelia -A.313, A.494

Grabinsky, Marliyn -A.314

Gradecki, Jennifer

Graham, Rocio

Graham, Sara -A.315, A.316, G.267

Granberg, Janice -G.117

Grant, Vicki -A.317

Green, Frank -A.318

Green, Michael -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.229

Greenwood, Vera -A.318.100

Greenspan, Shlomi -G.290

Gregson, Sandra -A.319

Groat, Maggie

Gronau, Anna -A.320

Grootveld, Belinda -A.107

Grunwald, Bettina -A.321, G.242.100

The GTA Collective

Guan, Yong Fei

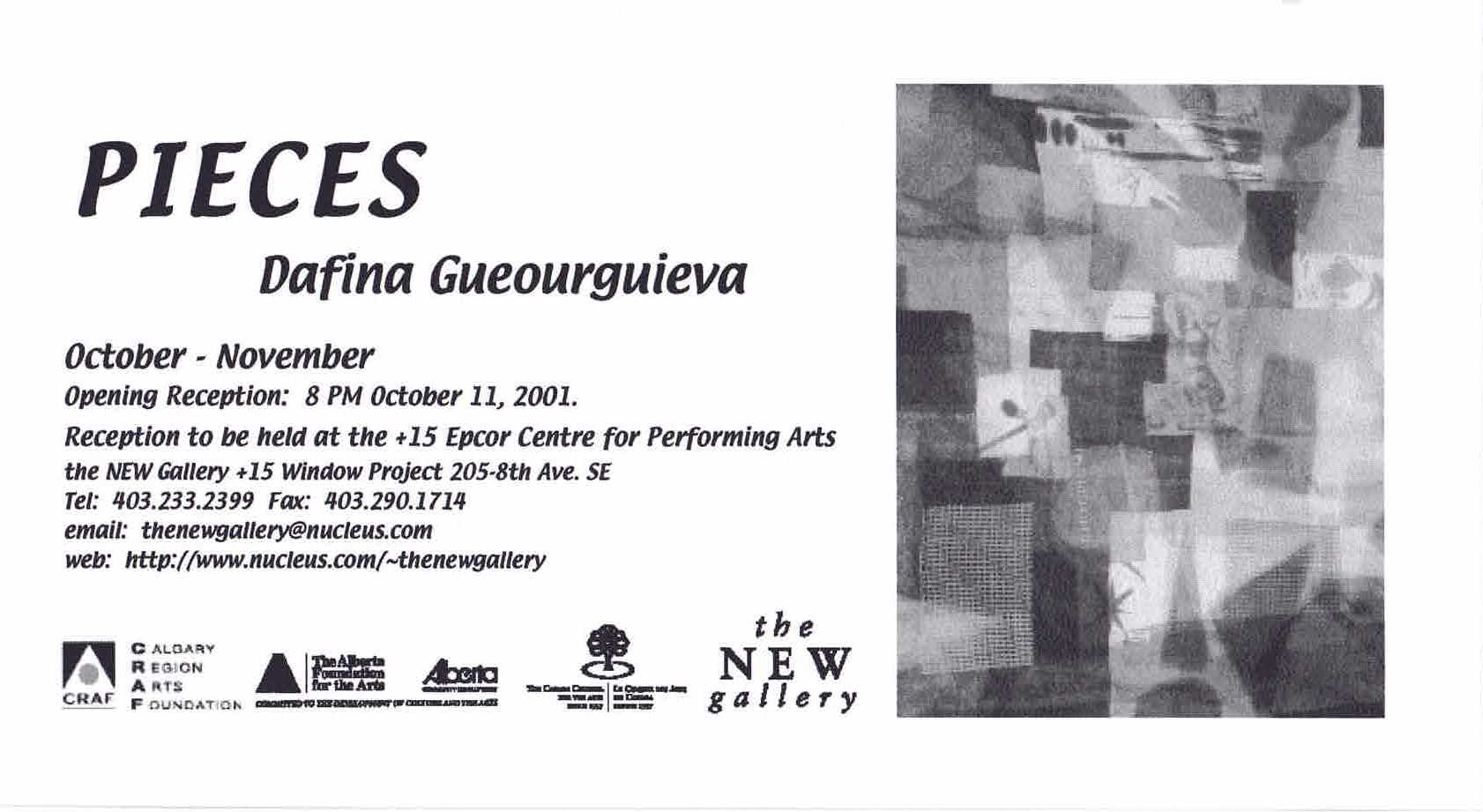

Gueourguieva, Dafina -A.322

Guha-Thakurta, Anu -A.323

Gundersen, Bruce -A.204.100

Gundersen, Jesper -G.293

Gustafson, Anna

Guttman, Freda -A.324

Gajda, Stefan -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Gallie, Tommy -G.124.50, G.214, G.214.1

Gammon, Lynda -A.293.100

Garcia, Sophie

Gardner-Popovac, Jasmine -A.294

Garlicki, Elizabeth -G.265

Garneau, David -A.295, G.109, G.149, G.234, G.242.100, G.278, G.279

Garrard, Rose -A.296

Garrett, Wayne

Gartley, Vera -A.297

Gaysek, Fred -A.298

Gerber, Natalie

Gerin, Annie -A.299

Gerz, Jochen -A.300

Geuer, Juan -A.301

Giammarino, Lorenzo -G.108.100

Giang, Paul -A.436.5

Gibson, Rick -A.302

Gibson, William -A.303

Gilbert, Gerry -A.304, G.182

Giles, Ken -A.305

Giles, Wayne - G.119, G.131, G.257, G.257.1, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Gillon, Annette -A.306

Gläser, Christine -G.114

Glenn, Allyson - A.269, A.307

Glenn, Mat

Godberson, Celine -G.158

Goertz, Jim -G.106

Gogal, Janice -G.117.100

Gogarty, Amy-A.308, G.117, G.244, G.244.1, G.257, G.257.1, G.261, G.266, G.277, G.278

Goldberg, Whoopi -A.309

Golden, Anne -G.158

Göllner, Adrian -A.310

Gooden, Tom - G.123.200

Goreas, Lee -A.311

Gorris, Susan -G.117.100

Gosselin, Marcel -A.312, G.299

Gossen, Cecelia -A.313, A.494

Grabinsky, Marliyn -A.314

Gradecki, Jennifer

Graham, Rocio

Graham, Sara -A.315, A.316, G.267

Granberg, Janice -G.117

Grant, Vicki -A.317

Green, Frank -A.318

Green, Michael -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.229

Greenwood, Vera -A.318.100

Greenspan, Shlomi -G.290

Gregson, Sandra -A.319

Groat, Maggie

Gronau, Anna -A.320

Grootveld, Belinda -A.107

Grunwald, Bettina -A.321, G.242.100

The GTA Collective

Guan, Yong Fei

Gueourguieva, Dafina -A.322

Guha-Thakurta, Anu -A.323

Gundersen, Bruce -A.204.100

Gundersen, Jesper -G.293

Gustafson, Anna

Guttman, Freda -A.324

H

Haas, Alyssa -A.394

Habermiller, Bart -A.325, G.219, G.227, G.251, G.257, G.257.1, G.277, G.311

Hadala, Helen - A.326, G.124.100

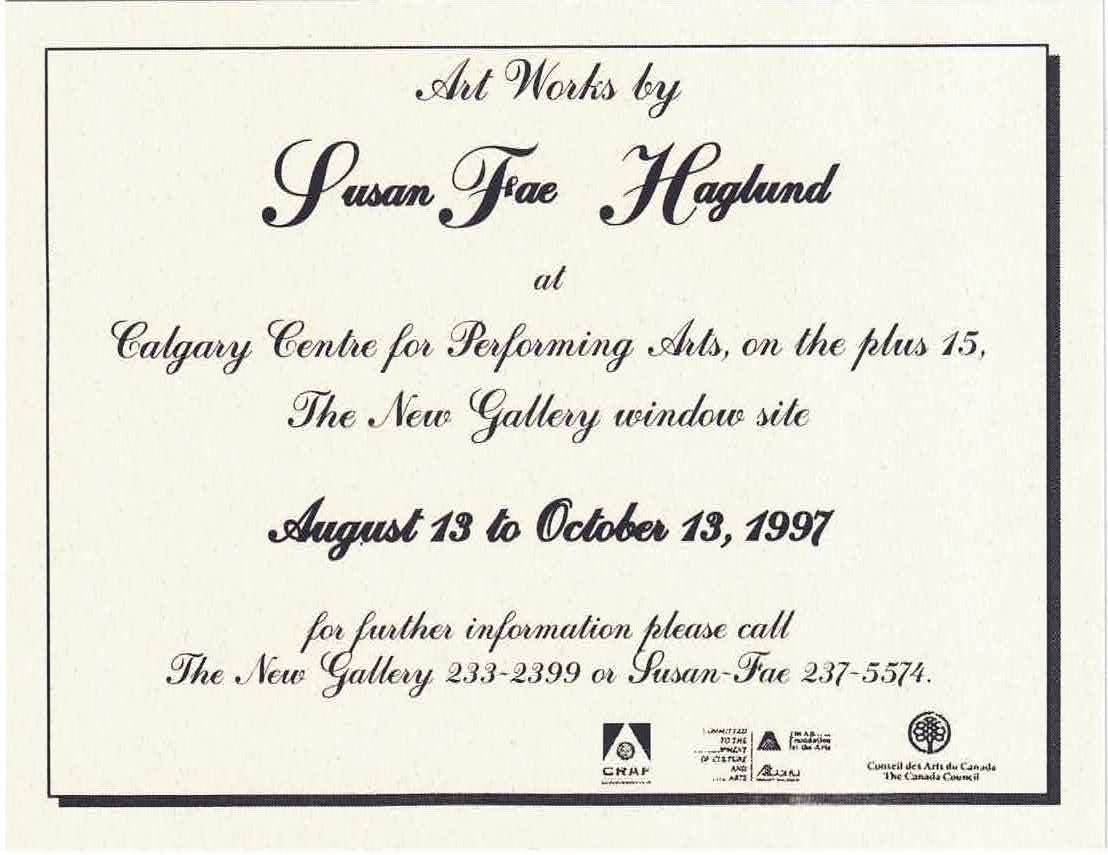

Haglund, Susan Fae -A.327

Hall, David

Hall, John -A.328, G.151, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.163, G.176, G.198, G.235, G.250, G.250.1, G.250.2, G.251, G.252, G.252.1

Hall, Joice -A.329, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.277

Hall, Pam -A.330

Hall, Shirley -A.331

Halley, Caroline -G.146

Hamilton, Reginald -A.332

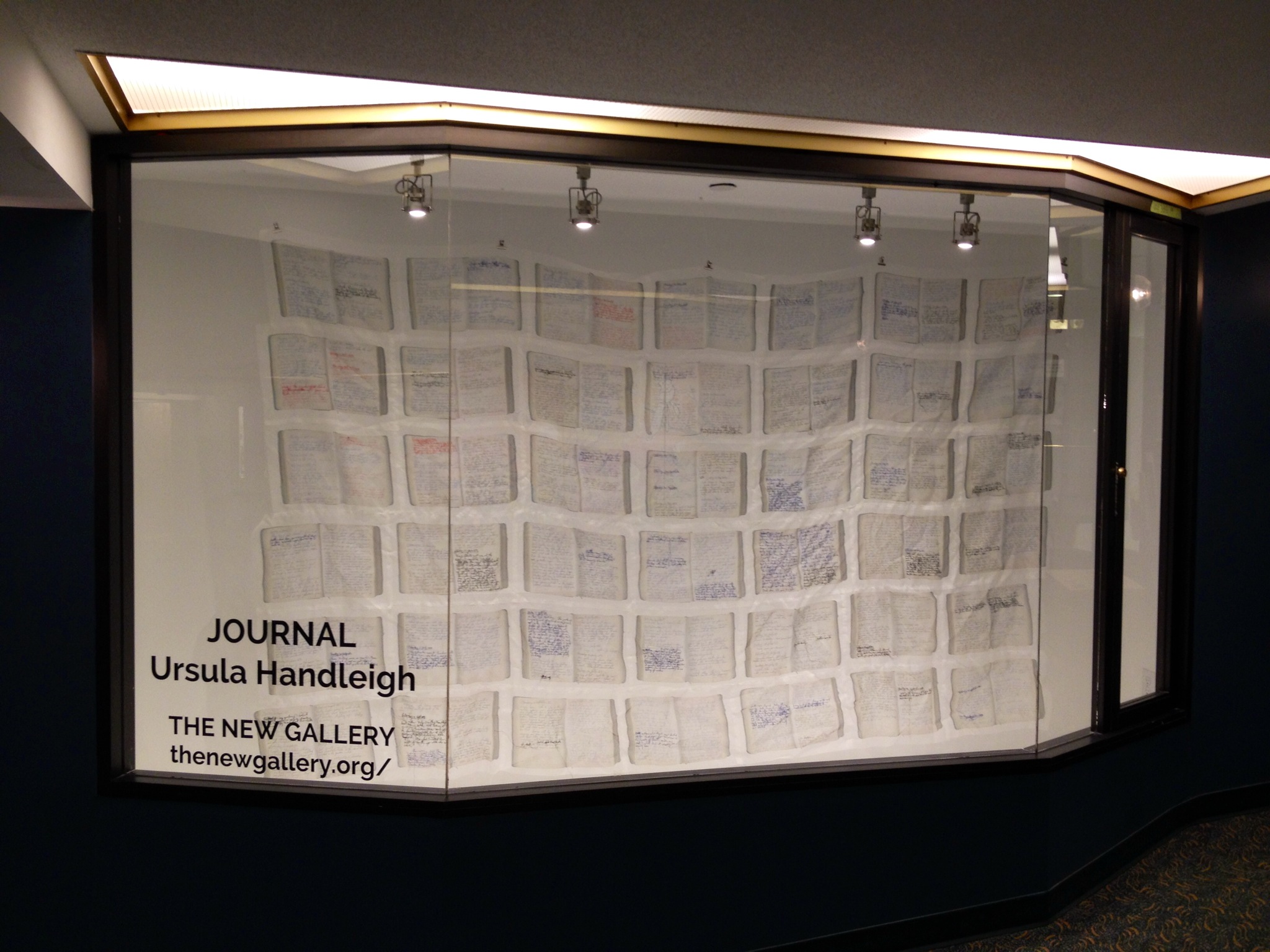

Handleigh, Ursula -A.333

Hanscom, Jay -A.334

Hansen, Mike -A.335

Harcsa, Lenke -A.336

Harding, Noel - A.337, G.113

Hardy, Ann - A.338

Hardy, Patricia -G.118, G.196, G.196.1

Hargrave, David -A.339

Harmsen, Alexander -G.106

Harris, Gail -A.340

Harrison, Amy -A.697

Hassall, Matt -A.201

Hauf, Hans-Peter -G.114

Hawke, Linda

Hawkins, Paulette -A.474, G.129

Heap of Birds, Hachivi Edgar A. -A.341

Heavyshield, Faye -A.342

Hebert, Amber -A.343

Heimbecker, Steve -A.217, A.344.1, A.344.5, G.205, G.205.1, G.214.100

Heintz, John L. -A.354.100

Heisler, Franklyn - A.345

Henderson, Clark Nikolai -A.346

Henderson, Jill -A.347

Henricks, Nelson -A.348, G.106, G.190, G.206, G.214.100, G.238, G.251, G.252, G.252.1, G.257,

G.257.1 G.257.2, G.277, G.311

Herbert, Simon -A.349

Hewes, Jane -A.217

Hewson, Paul -A.350, G.301

Heyd, Thomas -G.244, G.244.1

Hiebert, Ted -A.351, A.351.1

Higgins, Dick -A.352

Hill, Blair David

Hill, Gabrielle L’Hirondelle

Hill, Gail -A.353

Hinchliffe, Ian -G.204

Ho, Carol -G.186

Ho-You, Jill

Hockenhull, James -A.354

Hodgan-Christiansen, Maureen -A.354.100

Hoey, Brian

Hoiberg, Joshua -A.354.200

Holm, Signy

Holmes, Charlie -A.355

Holt, Timothy

von Holtz, Lucretia -G.259.100

Holzer, Jenny

Horowitz, Marc -G.256

Horowitz, Risa S. -A.356

HORSE Collective

Hoszko, Sheena -A.357

Houde, Marie-Andrée -A.358

Houle, Robert -A.359

Houle, Terrance -A.360

Housley, Kirk -G.102

Howard, Keith -G.145.100

Howes, Mary -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Hoy, Declan

Hu, Brubey -G.271.100

Hu, Helen

Hudson, Dan

Hughes, Chuck

Hughes, Lynn -A.361

Hume, Brent -A.362

Hume, Vern -A.363, A.363.1, G.135, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.206, G.274, G.295

Humniski, Dara

Hung, Roselina -A.364

Hunter, Geoffrey -A.365, G.174.100, G.176, G.252, G.252.1 G.257, G.257.1, G.266

Huot, Claire -A.368

Hushlak, Gerald - G.50, G.135

Hutchinson, Lynne -G.245, G.245.1

Hutchinson (Hutch), M. -A.366

Hutton, Jen -A.367

Hutton, Randy - G.137

Huxtable, Tamara -A.369

Huynh, Kim -A.370

Huysman, Adrian -A.371

Habermiller, Bart -A.325, G.219, G.227, G.251, G.257, G.257.1, G.277, G.311

Hadala, Helen - A.326, G.124.100

Haglund, Susan Fae -A.327

Hall, David

Hall, John -A.328, G.151, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.163, G.176, G.198, G.235, G.250, G.250.1, G.250.2, G.251, G.252, G.252.1

Hall, Joice -A.329, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.277

Hall, Pam -A.330

Hall, Shirley -A.331

Halley, Caroline -G.146

Hamilton, Reginald -A.332

Handleigh, Ursula -A.333

Hanscom, Jay -A.334

Hansen, Mike -A.335

Harcsa, Lenke -A.336

Harding, Noel - A.337, G.113

Hardy, Ann - A.338

Hardy, Patricia -G.118, G.196, G.196.1

Hargrave, David -A.339

Harmsen, Alexander -G.106

Harris, Gail -A.340

Harrison, Amy -A.697

Hassall, Matt -A.201

Hauf, Hans-Peter -G.114

Hawke, Linda

Hawkins, Paulette -A.474, G.129

Heap of Birds, Hachivi Edgar A. -A.341

Heavyshield, Faye -A.342

Hebert, Amber -A.343

Heimbecker, Steve -A.217, A.344.1, A.344.5, G.205, G.205.1, G.214.100

Heintz, John L. -A.354.100

Heisler, Franklyn - A.345

Henderson, Clark Nikolai -A.346

Henderson, Jill -A.347

Henricks, Nelson -A.348, G.106, G.190, G.206, G.214.100, G.238, G.251, G.252, G.252.1, G.257,

G.257.1 G.257.2, G.277, G.311

Herbert, Simon -A.349

Hewes, Jane -A.217

Hewson, Paul -A.350, G.301

Heyd, Thomas -G.244, G.244.1

Hiebert, Ted -A.351, A.351.1

Higgins, Dick -A.352

Hill, Blair David

Hill, Gabrielle L’Hirondelle

Hill, Gail -A.353

Hinchliffe, Ian -G.204

Ho, Carol -G.186

Ho-You, Jill

Hockenhull, James -A.354

Hodgan-Christiansen, Maureen -A.354.100

Hoey, Brian

Hoiberg, Joshua -A.354.200

Holm, Signy

Holmes, Charlie -A.355

Holt, Timothy

von Holtz, Lucretia -G.259.100

Holzer, Jenny

Horowitz, Marc -G.256

Horowitz, Risa S. -A.356

HORSE Collective

Hoszko, Sheena -A.357

Houde, Marie-Andrée -A.358

Houle, Robert -A.359

Houle, Terrance -A.360

Housley, Kirk -G.102

Howard, Keith -G.145.100

Howes, Mary -G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Hoy, Declan

Hu, Brubey -G.271.100

Hu, Helen

Hudson, Dan

Hughes, Chuck

Hughes, Lynn -A.361

Hume, Brent -A.362

Hume, Vern -A.363, A.363.1, G.135, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.206, G.274, G.295

Humniski, Dara

Hung, Roselina -A.364

Hunter, Geoffrey -A.365, G.174.100, G.176, G.252, G.252.1 G.257, G.257.1, G.266

Huot, Claire -A.368

Hushlak, Gerald - G.50, G.135

Hutchinson, Lynne -G.245, G.245.1

Hutchinson (Hutch), M. -A.366

Hutton, Jen -A.367

Hutton, Randy - G.137

Huxtable, Tamara -A.369

Huynh, Kim -A.370

Huysman, Adrian -A.371

I

Ibghy, Richard -A.431

Ifko, Levin -A.371.5

Iga, Yuriko -A.372

Ingalls, Tomo -G.315.5

Inuzuka, Sadashi -A.373

Iranzo, Irma -G.245, G.245.1

Ireland, Jennifer

Irwin, Jed -A.374, G.311, G.314

Isabella, Nadya

Ivall, Lynn -A.375

Ivey, Kristin -A.376

Ifko, Levin -A.371.5

Iga, Yuriko -A.372

Ingalls, Tomo -G.315.5

Inuzuka, Sadashi -A.373

Iranzo, Irma -G.245, G.245.1

Ireland, Jennifer

Irwin, Jed -A.374, G.311, G.314

Isabella, Nadya

Ivall, Lynn -A.375

Ivey, Kristin -A.376

J

Jackson, Paul -A.377

Jacob, Luis - A.378

Jacobson, Melody - A.379, G.174.100

Jahraus, Audrey

James, Rachel

Janvier, Alex -G.280

Jarvis, Aaron -A.381

Jenkins, Adrienne -A.382

Jennings, Packard -G.256

Jim, Calvin D.

Jivraj, Christophe -A.383

Jodoin, André -A.384, G.50, G.241

John, Sarah -G.118

Johnson, Eve M

Johnson, Luke -G. 168.05

Johnson, Marcia -A.386

Johnson, Oliver -A.422

Johnston, Teresa -A.387

Jolicoeur, Nicole

Jones, Colby -G.178.100

Jonsson, Tomas -A.388, A.428, G.125, G.200, G.215, G.149, G.228.100, G.256, G.304.100

Jorritsma, Marijke -G.256

Joseph, Clifton -A.206

Juan, Gever -A.301

Jule, Walter -A.389

Juliusson, Svava -A.389.100

Jupitter-Larsen, Gerald -A.390

Jacob, Luis - A.378

Jacobson, Melody - A.379, G.174.100

Jahraus, Audrey

James, Rachel

Janvier, Alex -G.280

Jarvis, Aaron -A.381

Jenkins, Adrienne -A.382

Jennings, Packard -G.256

Jim, Calvin D.

Jivraj, Christophe -A.383

Jodoin, André -A.384, G.50, G.241

John, Sarah -G.118

Johnson, Eve M

Johnson, Luke -G. 168.05

Johnson, Marcia -A.386

Johnson, Oliver -A.422

Johnston, Teresa -A.387

Jolicoeur, Nicole

Jones, Colby -G.178.100

Jonsson, Tomas -A.388, A.428, G.125, G.200, G.215, G.149, G.228.100, G.256, G.304.100

Jorritsma, Marijke -G.256

Joseph, Clifton -A.206

Juan, Gever -A.301

Jule, Walter -A.389

Juliusson, Svava -A.389.100

Jupitter-Larsen, Gerald -A.390

K

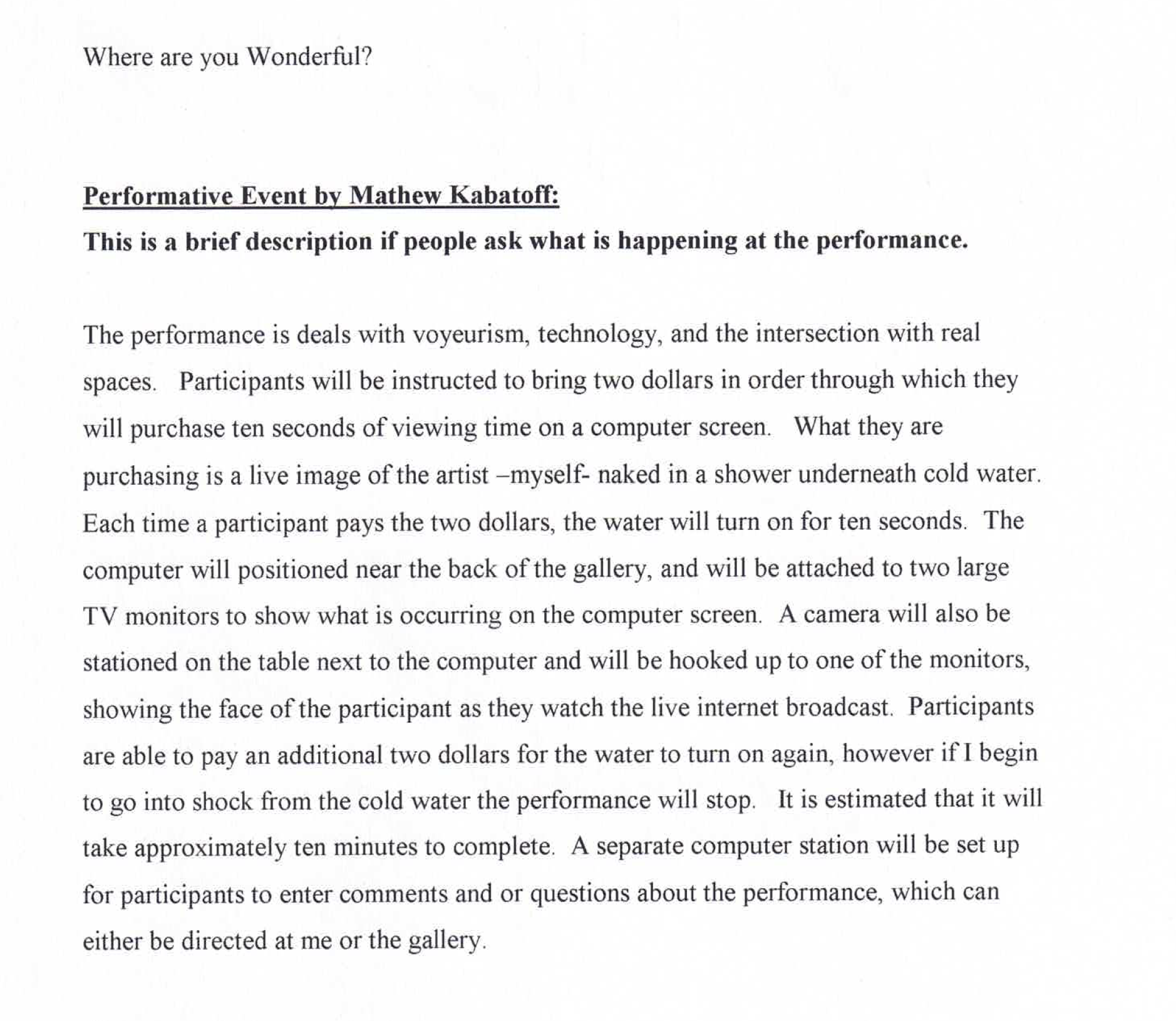

Kabatoff, Mathew -A.391

Kablusiak -A.440

Kalisch, Edward -G.242.100

Kalmenson, Felix -A.392

Kantor, Istvan -A.393, G.200, G.201

Karsten, Jayda -A.394

Kavanaugh, Laura -G.149, G.211, G.263

Kawamura, Toyo -G.165

Keim, Alexandra - A.354.100

Kelly, Joe -A.395

Kelly, Michael -A.396

Ken, Steph Wong

Kennedy, Kathy -A.397

Kennedy, Shauna -A.398

Kerbel, Janice -A.399

Kerr, Colleen -A.400, G.206, G.214.100, G.238, G.242.100, G.257.2, G.272, G.274

Khan, Nazeer -G.245, G.245.1

Kick, Urs -A.401

Kidd, Jane - G.204.100

Kierspel, Jürgen -A.402, G.114, G.237, G.114, G.114.1

Kim, Mary -A.403, G.102

King, Pam -A.404, G.286

King, Romana -A.405

Kinsella, Fiona -A.406

Kisseleva, Olga -A.407

KIT - G.192, G.249

Kite, Suzanne -A.408

Kiyooka, Harry -A.409

Klassen, Christine -A.201

Klimek, Lylian -A.410

Knelman, Sara

Kneubühler, Thomas

Kniss, Garry -G.184.100, G.253.200, G.310

Ko, Jinhan -A.411

Koh, Germaine -A.399

Kokoska, Mary-Ann -A.412

Kolijn, Eveline

Koller, George -A.413

Konadu, Luther -A.413.15

Kongsuwan, Irena M.

Konyves, Tom -A.414, A.528

Koop, Wanda -A.417

Koprek, Cheryl -G.106

Koschzek, Rai -A.154, A.415, G.123.200, G.124.50, G.215, G.253.200

Kotlaris, Johanna

Kottmann, Don -A.416, G.176, G.198

Kramer, Mark

Krulis, Kamil -A.418, G.252, G.252.1

Krynski, Bryce

‘Ksan Performing Arts

Kubota, Nobuo

Kupka, Michael -A.139.100, G.75

Kuras, Christian -A.419

Kwandibens, Nadya -G.283

Kwong, Alex

Kyba, Matthew -A.419.5

Kablusiak -A.440

Kalisch, Edward -G.242.100

Kalmenson, Felix -A.392

Kantor, Istvan -A.393, G.200, G.201

Karsten, Jayda -A.394

Kavanaugh, Laura -G.149, G.211, G.263

Kawamura, Toyo -G.165

Keim, Alexandra - A.354.100

Kelly, Joe -A.395

Kelly, Michael -A.396

Ken, Steph Wong

Kennedy, Kathy -A.397

Kennedy, Shauna -A.398

Kerbel, Janice -A.399

Kerr, Colleen -A.400, G.206, G.214.100, G.238, G.242.100, G.257.2, G.272, G.274

Khan, Nazeer -G.245, G.245.1

Kick, Urs -A.401

Kidd, Jane - G.204.100

Kierspel, Jürgen -A.402, G.114, G.237, G.114, G.114.1

Kim, Mary -A.403, G.102

King, Pam -A.404, G.286

King, Romana -A.405

Kinsella, Fiona -A.406

Kisseleva, Olga -A.407

KIT - G.192, G.249

Kite, Suzanne -A.408

Kiyooka, Harry -A.409

Klassen, Christine -A.201

Klimek, Lylian -A.410

Knelman, Sara

Kneubühler, Thomas

Kniss, Garry -G.184.100, G.253.200, G.310

Ko, Jinhan -A.411

Koh, Germaine -A.399

Kokoska, Mary-Ann -A.412

Kolijn, Eveline

Koller, George -A.413

Konadu, Luther -A.413.15

Kongsuwan, Irena M.

Konyves, Tom -A.414, A.528

Koop, Wanda -A.417

Koprek, Cheryl -G.106

Koschzek, Rai -A.154, A.415, G.123.200, G.124.50, G.215, G.253.200

Kotlaris, Johanna

Kottmann, Don -A.416, G.176, G.198

Kramer, Mark

Krulis, Kamil -A.418, G.252, G.252.1

Krynski, Bryce

‘Ksan Performing Arts

Kubota, Nobuo

Kupka, Michael -A.139.100, G.75

Kuras, Christian -A.419

Kwandibens, Nadya -G.283

Kwong, Alex

Kyba, Matthew -A.419.5

L

L’Hirondelle, Cheryl -A.420

Labovitz, Vikki -A.154, A.421

Lacy, Steve -A.422

Ladies’ Invitational Deadbeat Society (LIDS)

Ladner-Zech, Sami -A.424

Laiwint, Jennifer -A.423

Lam, Amy

Lambert, Mathieu

Lambert, Steve -G.256

Landin, Aurora

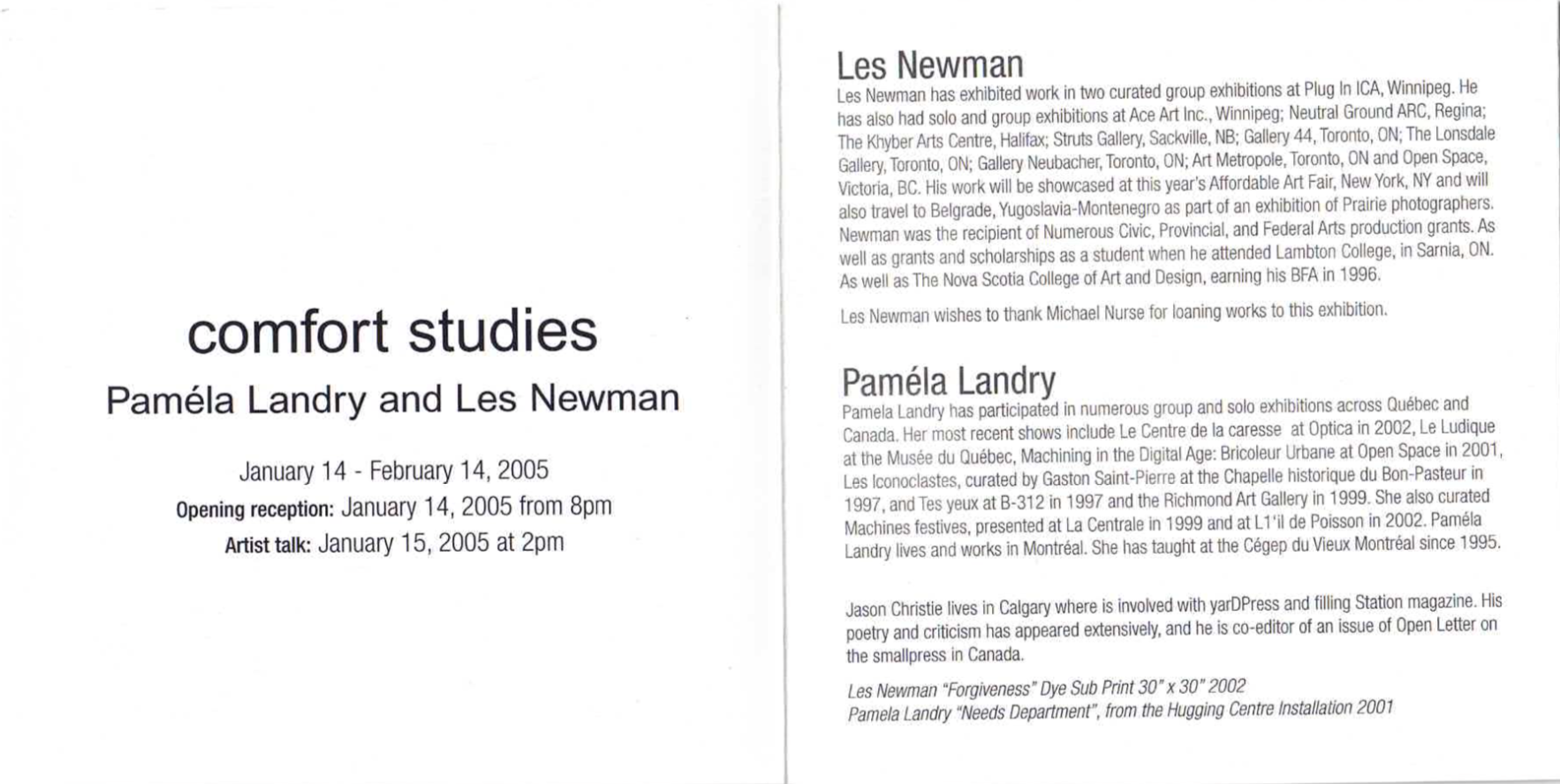

Landry, Paméla -A.425, A.538

Langford, Jon -A.426

Larsen, Anna-Marie -G.107

Larson, Nare -A.427

Larsson, Rina -A.428

Latitude 53

Latour, Toni -A.428

Lau, Rachel -A.428.5

Lauchlan, Natalie

Layzell, Richard -A.429

Learn, Beth

LeBlanc, Valerie -G.304.100

Lee, Ahreum

Lee, Serena

Lee, Su-Ying

Leeming, Frances -A.430, A.590

Leffler-Akill, Wanda -A.474, G.129

Lemecha, Vera - G.241

Lemieux, Lisette -G.130

Lemmens, Marilou -A.431

Lennox, Sheena - A.354.100

Lepley, Debbie

Lessard, Denis -A.332

Levesque, Anita -A.433

Levy, Bill -A.434

Lewis, Marien

Lewis, Michael -A.435

Lexier, Micah -A.436

Li, Simon -G.271.100

Li, Wei -A.436.2

Liang, Kev -A.436.5

Licht, David

Ligtvoet, Kiona Callihoo -A.436.100

Lim, Milton

Lindenberg, Mat

Linklater, Duane -A.437, G.283

Linklater, Tanya Lukin

Lipton, Lisa -A.438

Lister, Ardele -A.439

Liu, An Te

Livedalen, Rachel -A.440

Loban, Conrad -G.165.100

Loban, Gillian -G.165.100

Lockwood, Frank -A.441

Loeffler, Carl -A.442

Lomow, Robert -A.443, G.314

Lord, Erica

Los-Jones, Tyler -A.487

Loschuk, Vicki -A.444

Louis-Adams, F. -A.669.1

Low Horn, Sikapinakii

Lowe, Larry Blackhorse -G.283

Lu, Henry Heng

Lukacs, Attila Richard

Lukeman, Paul -A.413, G.174

Lum, Maymee Ying -A.445

Lum, Morris

Lund, Ginette

Lundeen, Patrick -G.109

Lundeen, Stacy -A.364

Luong, Alvin

Luong, Danny

Lupypciw, Wednesday - G.231.100, G.193

Lyon, George -A.446

Lytle, Donna -A.228

Labovitz, Vikki -A.154, A.421

Lacy, Steve -A.422

Ladies’ Invitational Deadbeat Society (LIDS)

Ladner-Zech, Sami -A.424

Laiwint, Jennifer -A.423

Lam, Amy

Lambert, Mathieu

Lambert, Steve -G.256

Landin, Aurora

Landry, Paméla -A.425, A.538

Langford, Jon -A.426

Larsen, Anna-Marie -G.107

Larson, Nare -A.427

Larsson, Rina -A.428

Latitude 53

Latour, Toni -A.428

Lau, Rachel -A.428.5

Lauchlan, Natalie

Layzell, Richard -A.429

Learn, Beth

LeBlanc, Valerie -G.304.100

Lee, Ahreum

Lee, Serena

Lee, Su-Ying

Leeming, Frances -A.430, A.590

Leffler-Akill, Wanda -A.474, G.129

Lemecha, Vera - G.241

Lemieux, Lisette -G.130

Lemmens, Marilou -A.431

Lennox, Sheena - A.354.100

Lepley, Debbie

Lessard, Denis -A.332

Levesque, Anita -A.433

Levy, Bill -A.434

Lewis, Marien

Lewis, Michael -A.435

Lexier, Micah -A.436

Li, Simon -G.271.100

Li, Wei -A.436.2

Liang, Kev -A.436.5

Licht, David

Ligtvoet, Kiona Callihoo -A.436.100

Lim, Milton

Lindenberg, Mat

Linklater, Duane -A.437, G.283

Linklater, Tanya Lukin

Lipton, Lisa -A.438

Lister, Ardele -A.439

Liu, An Te

Livedalen, Rachel -A.440

Loban, Conrad -G.165.100

Loban, Gillian -G.165.100

Lockwood, Frank -A.441

Loeffler, Carl -A.442

Lomow, Robert -A.443, G.314

Lord, Erica

Los-Jones, Tyler -A.487

Loschuk, Vicki -A.444

Louis-Adams, F. -A.669.1

Low Horn, Sikapinakii

Lowe, Larry Blackhorse -G.283

Lu, Henry Heng

Lukacs, Attila Richard

Lukeman, Paul -A.413, G.174

Lum, Maymee Ying -A.445

Lum, Morris

Lund, Ginette

Lundeen, Patrick -G.109

Lundeen, Stacy -A.364

Luong, Alvin

Luong, Danny

Lupypciw, Wednesday - G.231.100, G.193

Lyon, George -A.446

Lytle, Donna -A.228

M

Mabie, Don -A.447, A.447.1, G.122, G.123, G.124.100, G.149, G.151, G.159, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.176, G.187,

G.215, G.216, G.224, G.224.1, G.225, G.227, G.232, G.238, G.242.100,

G.257, G.257.1, G.260, G.277, G.296, G.305, G.306, G.312, G.312.1, G.314

MacDonald, Jody -A.449

MacDonnell, William -A.448

MacEachern, Scott - G.234.300

Maciejko, Kaylee

MacInnis, Neil -A.450

MacKay, Allan Harding -A.451

MacKinnon, Angus -A.452, G.311

MacKinnon, Shannon -A.453

MacLean, Laurie -G.124.100

MacLennan, Alistair -A.454

Macleod, Myfawny -A.455

Magpie -A.397

Mahovsky, Trevor -A.456

Mahr, Sigrid

Majer, Juli

Majzels, Robert -A.368

Mandseth, Chris -G.292

Mansell, Alice -A.457, G.198

ManWoman -A.458, G.176, G.257, G.257.1

mantis mei

Mark, Matthew -A.487

Markotic, Yvonne -A.459, G.239

Mars, Tanya -A.460, G.298

Marsden, Scott -A.461

Marsh, Lynne -A.462

Marsh, Ruth -A.463

Marshall, Gregory - G.242.100

Marshall, Teresa - G.270, G.270.1

Martin, Annie -A.464

Martin, Messi -A.465

Martin, Tony -A.465.100, G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100

Martineau, Luanne -A.354.100, A.466

Martinis, Dalibor -A.467

Mass, Sherrill -A.468

Masters, Chris -A.469

Mathis, Jason -A.470

Mathur, Ashok -A.471, A.472, G.242.100

Matta-Clark, Gordon

Mawani, Selma - G.242.100

May, Walter -A.473, A.474, A.475, G.129, G.132, G.134, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.163, G.196, G.196.1, G.205, G.214, G.214.1, G.215, G.216, G.257, G.257.1, G.260, G.277

Mayer, Jillian

Mayes, Malcolm -A.474, G.129

Mayes, Michael -A.474, G.129

Mayr, Suzette -A.166

Mayrhofer, Ingrid -G.245, G.245.1

Mazinani, Sanaz

McAffee, Dionne

McCabe, Penny -G.245, G.245.1

McCaffery, Steve

McCaffrey, Gregg -A.233, A.495

McCall, Khadejha -G.130

McCallum, Kirstie -A.496

McCan, Shana -A.498

McCann, CB

McCarroll, Billy -A.497, G.181.100, G.234

McCaw, Shana -G.309

McClure, Robert -A.499, G.131, G.260

McConnell, Clyde -A.500

McCullough, Jane -G.309

McDonald, Fred -A.501

McDougall, James -A.502, G.120

McFadden, Kegan -G.284, G.285

McFaul, George -A.503, G.196, G.196.1

McGrath, Tammy

McGregor, Kathryn -A.148

McGregor, Wade -A.481, G.136, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.258

McHugh, Bryan -A.352

McKenna, Brian -A.482

McKenzie, Lesley -G.265

McKeough, Frank -A.483

McKeough, Rita -A.484, A.485, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.210, G.258, G.307

McKinnon, John - A.485.100

McKinven, Alastair -A.477

McLaren, Andrew A.

McLaren, Paul -A.486

McLean, Michaelle -A.478, G.166

McLeod, Nate -A.487

McMackon, Jennifer -A.488, A.504

McNab, Anthony

McNeil, Joan -A.479

McPhail, Andrew -A.505

McQueen, Kari -A.489

McQuitty, Jane -A.490

McSherry, Fred -G.130

McTrowe, Mary-Anne -A.491, A.492

McVeigh, Don -A.473, G.132

McVeigh, Jennifer -A.493, G.228.100

Meade, Celia -A.494

Mehra, Divya -A.506

Meichel, Dan - G.263

Melnyk, Doug -A.507, G.301

Menard, Cindy -G.102

Mendelson Joe -A.385

Merchant, Rithika

Mersault, JD -A.508

Mesquita, Ivo Costa -A.509

Meuwissen, Roy -G.230

Mia & Eric

Michelena, Miguel

Middleton, Rory -A.510

Migue, Kuhlein

Mikols, Lauren -G.291

Miles, Kirk -A.503, A.511, G.196, G.196.1, G.229

Millan, Lorri -G.199

Millar, Cam

Millard, Laura -G.240

Miller, Juliana -A.513, G. 281.100

Miller, Rebekah -A.512

Miller, Shanna -A.514

Mills, Royden -A.188

Milo, Michael - A.514.100, G.106, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Milthorp, Robert -A.515, A.516, A.517, G.118, G.127, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.206, G.219, G.227, G.257,

G.257.1, G.295, G.311

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. -A.518

Mitchell, Charles - G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100, G.308

Mitchell, Jackson -A.519

Mochizuki, Cindy

Modigliani, Leah

Moffat, Ellen -A.520

Moller, Peter -A.521, G.101, G.137, G.181.100, G.257, G.257.1

Monk, Meredith -A.522

Monkman, Kent -A.523

Monroe, Deanne - G.123, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.295

Montadas, Antonio -A.532

Moody, Robyn -A524, A.525

Mootoo, Shani -A.526

Moppett, Carroll

Moppett, Ron-G.118, G.119, G.151, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.215, G.236, G.250, G.250.1, G.250.2 Mora, Cris -A.525

Morosoli, Joélle -A.527

Morris, Ken -A.528

Morstad, Julie -A. 269, A.307, A.529

Mortimer, Karly -G.146

Moschopedis, Eric -A.530

Mosher, Jay -A.510

Mountain, Harry -A.531

Mueller, Stephen -A.533

Mühleck, Georg -G.114

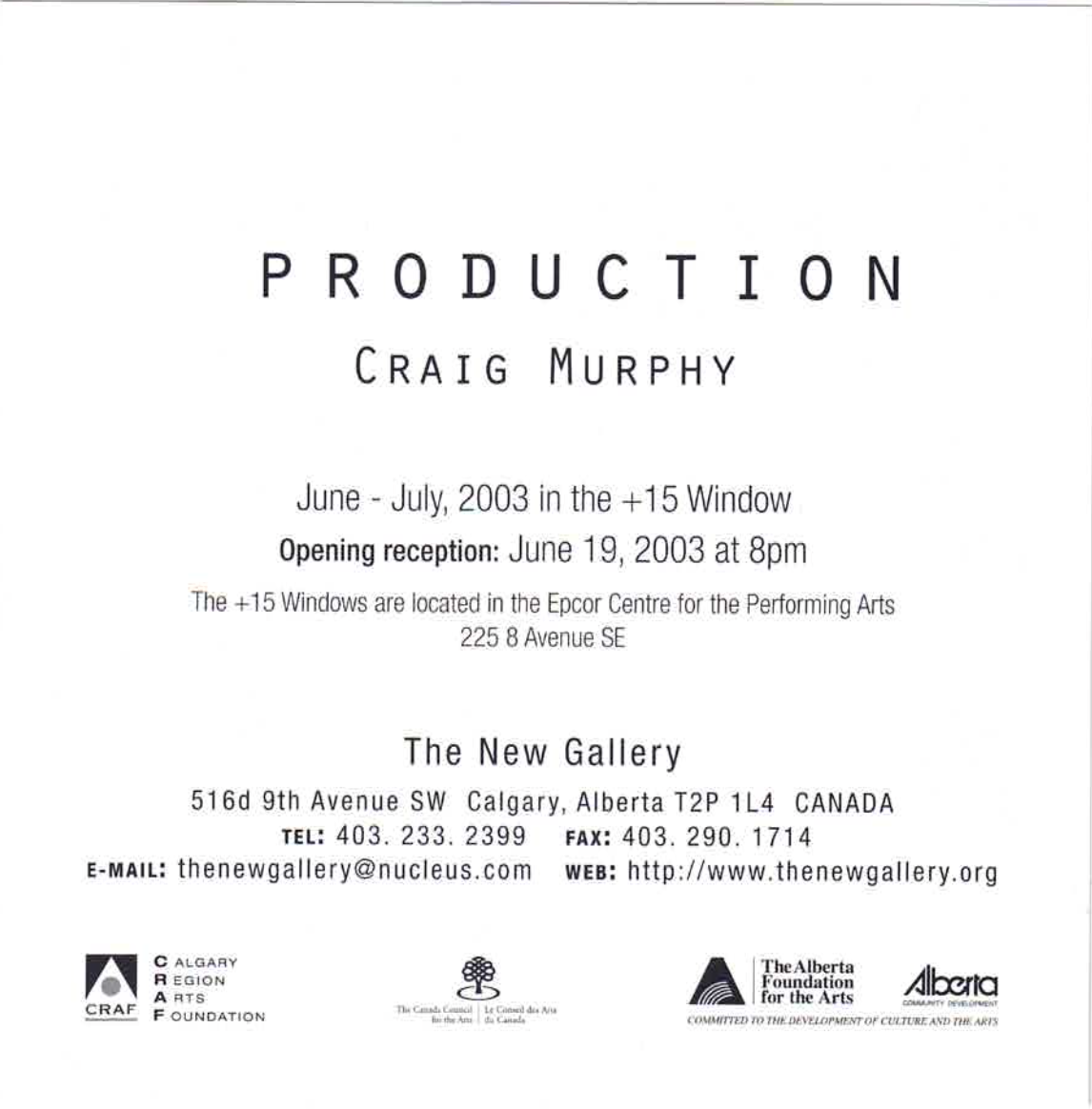

Murphy, Craig -A.534, G.148

G.215, G.216, G.224, G.224.1, G.225, G.227, G.232, G.238, G.242.100,

G.257, G.257.1, G.260, G.277, G.296, G.305, G.306, G.312, G.312.1, G.314

MacDonald, Jody -A.449

MacDonnell, William -A.448

MacEachern, Scott - G.234.300

Maciejko, Kaylee

MacInnis, Neil -A.450

MacKay, Allan Harding -A.451

MacKinnon, Angus -A.452, G.311

MacKinnon, Shannon -A.453

MacLean, Laurie -G.124.100

MacLennan, Alistair -A.454

Macleod, Myfawny -A.455

Magpie -A.397

Mahovsky, Trevor -A.456

Mahr, Sigrid

Majer, Juli

Majzels, Robert -A.368

Mandseth, Chris -G.292

Mansell, Alice -A.457, G.198

ManWoman -A.458, G.176, G.257, G.257.1

mantis mei

Mark, Matthew -A.487

Markotic, Yvonne -A.459, G.239

Mars, Tanya -A.460, G.298

Marsden, Scott -A.461

Marsh, Lynne -A.462

Marsh, Ruth -A.463

Marshall, Gregory - G.242.100

Marshall, Teresa - G.270, G.270.1

Martin, Annie -A.464

Martin, Messi -A.465

Martin, Tony -A.465.100, G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100

Martineau, Luanne -A.354.100, A.466

Martinis, Dalibor -A.467

Mass, Sherrill -A.468

Masters, Chris -A.469

Mathis, Jason -A.470

Mathur, Ashok -A.471, A.472, G.242.100

Matta-Clark, Gordon

Mawani, Selma - G.242.100

May, Walter -A.473, A.474, A.475, G.129, G.132, G.134, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.163, G.196, G.196.1, G.205, G.214, G.214.1, G.215, G.216, G.257, G.257.1, G.260, G.277

Mayer, Jillian

Mayes, Malcolm -A.474, G.129

Mayes, Michael -A.474, G.129

Mayr, Suzette -A.166

Mayrhofer, Ingrid -G.245, G.245.1

Mazinani, Sanaz

McAffee, Dionne

McCabe, Penny -G.245, G.245.1

McCaffery, Steve

McCaffrey, Gregg -A.233, A.495

McCall, Khadejha -G.130

McCallum, Kirstie -A.496

McCan, Shana -A.498

McCann, CB

McCarroll, Billy -A.497, G.181.100, G.234

McCaw, Shana -G.309

McClure, Robert -A.499, G.131, G.260

McConnell, Clyde -A.500

McCullough, Jane -G.309

McDonald, Fred -A.501

McDougall, James -A.502, G.120

McFadden, Kegan -G.284, G.285

McFaul, George -A.503, G.196, G.196.1

McGrath, Tammy

McGregor, Kathryn -A.148

McGregor, Wade -A.481, G.136, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.258

McHugh, Bryan -A.352

McKenna, Brian -A.482

McKenzie, Lesley -G.265

McKeough, Frank -A.483

McKeough, Rita -A.484, A.485, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.210, G.258, G.307

McKinnon, John - A.485.100

McKinven, Alastair -A.477

McLaren, Andrew A.

McLaren, Paul -A.486

McLean, Michaelle -A.478, G.166

McLeod, Nate -A.487

McMackon, Jennifer -A.488, A.504

McNab, Anthony

McNeil, Joan -A.479

McPhail, Andrew -A.505

McQueen, Kari -A.489

McQuitty, Jane -A.490

McSherry, Fred -G.130

McTrowe, Mary-Anne -A.491, A.492

McVeigh, Don -A.473, G.132

McVeigh, Jennifer -A.493, G.228.100

Meade, Celia -A.494

Mehra, Divya -A.506

Meichel, Dan - G.263

Melnyk, Doug -A.507, G.301

Menard, Cindy -G.102

Mendelson Joe -A.385

Merchant, Rithika

Mersault, JD -A.508

Mesquita, Ivo Costa -A.509

Meuwissen, Roy -G.230

Mia & Eric

Michelena, Miguel

Middleton, Rory -A.510

Migue, Kuhlein

Mikols, Lauren -G.291

Miles, Kirk -A.503, A.511, G.196, G.196.1, G.229

Millan, Lorri -G.199

Millar, Cam

Millard, Laura -G.240

Miller, Juliana -A.513, G. 281.100

Miller, Rebekah -A.512

Miller, Shanna -A.514

Mills, Royden -A.188

Milo, Michael - A.514.100, G.106, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Milthorp, Robert -A.515, A.516, A.517, G.118, G.127, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.206, G.219, G.227, G.257,

G.257.1, G.295, G.311

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. -A.518

Mitchell, Charles - G.75, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100, G.308

Mitchell, Jackson -A.519

Mochizuki, Cindy

Modigliani, Leah

Moffat, Ellen -A.520

Moller, Peter -A.521, G.101, G.137, G.181.100, G.257, G.257.1

Monk, Meredith -A.522

Monkman, Kent -A.523

Monroe, Deanne - G.123, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.295

Montadas, Antonio -A.532

Moody, Robyn -A524, A.525

Mootoo, Shani -A.526

Moppett, Carroll

Moppett, Ron-G.118, G.119, G.151, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.215, G.236, G.250, G.250.1, G.250.2 Mora, Cris -A.525

Morosoli, Joélle -A.527

Morris, Ken -A.528

Morstad, Julie -A. 269, A.307, A.529

Mortimer, Karly -G.146

Moschopedis, Eric -A.530

Mosher, Jay -A.510

Mountain, Harry -A.531

Mueller, Stephen -A.533

Mühleck, Georg -G.114

Murphy, Craig -A.534, G.148

N

Nachtigal, Conroy -A.536, G.242.100

Nagata, Kerry -A.354.100

Nakagawa, Ann Marie -A.535, G.149

Nam, Hwayeon

Nelles, Tammy -A.537

Neu, Noreen -G.117

Neufeld, Grant -G.228.100

Newman, Holly - A.540.100, G.256.100

Newman, Les -A.425, A.538

Newton, Alma -A.541

Ng, Petrina -A.542.5

Nguyen, Jacqueline Hoang -A.542

Nguyen, My Le -A.543

Nicol, Nancy -A.539

Nigro, Richard -G.113

NIK

Niro, Shelley -G.245, G.245.1

Nisbet, Nancy

Nishimura, Arthur - G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.257, G.257.1

Noguchi, Louise -A.544

Norgren, Jeff -A.545, A.545.1, G.241

Nordlund, Ryan -A.155, G.208.200

Normoyle, Michelle -A.547

Norouzi, Anahita -A.547.5

Nothing, Peter -A.548, G.196, G.196.1

Notzold, Paul -A.549

Nowatschin, Liz -A.550

Nowicka, Aneta -A.551

Nunoda, Steven - G.50, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.244, G.244.1, G.270, G.270.1

Nagata, Kerry -A.354.100

Nakagawa, Ann Marie -A.535, G.149

Nam, Hwayeon

Nelles, Tammy -A.537

Neu, Noreen -G.117

Neufeld, Grant -G.228.100

Newman, Holly - A.540.100, G.256.100

Newman, Les -A.425, A.538

Newton, Alma -A.541

Ng, Petrina -A.542.5

Nguyen, Jacqueline Hoang -A.542

Nguyen, My Le -A.543

Nicol, Nancy -A.539

Nigro, Richard -G.113

NIK

Niro, Shelley -G.245, G.245.1

Nisbet, Nancy

Nishimura, Arthur - G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.257, G.257.1

Noguchi, Louise -A.544

Norgren, Jeff -A.545, A.545.1, G.241

Nordlund, Ryan -A.155, G.208.200

Normoyle, Michelle -A.547

Norouzi, Anahita -A.547.5

Nothing, Peter -A.548, G.196, G.196.1

Notzold, Paul -A.549

Nowatschin, Liz -A.550

Nowicka, Aneta -A.551

Nunoda, Steven - G.50, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.244, G.244.1, G.270, G.270.1

O

O’Donnell, Jaynus -A.552

Ochiena, Rob -A.157

Oellers, Jeanette -G.114

Olaniyi-Davies, Nike -A.553

Olbrich, Jürgen O. -A.554, G.159, G.187, G.225, G.227, G.232, G.312, G.312.1

Oliveira, Susy

Oliver, Cody -G.110

Ollenberger, Leanne -A.555

Olson, Daniel -A.556, G.249

O’Neill, Kathleen - G.142

Ono, Yoko -A.557

Osborne, B.G. -A.557.100

Osuntokun, Keyede

Ouchi, Conrad -G.109

Oullet, Shelley -A.558, G.218.100

Ouellette, Kim -A.559

Oyawale, Christina -A.559.100

Oxenbury, Glen -G.174.200, G.310

Ozeri, Moshe - G.124, G.160, G.206, G.242.100, G.295

Ochiena, Rob -A.157

Oellers, Jeanette -G.114

Olaniyi-Davies, Nike -A.553

Olbrich, Jürgen O. -A.554, G.159, G.187, G.225, G.227, G.232, G.312, G.312.1

Oliveira, Susy

Oliver, Cody -G.110

Ollenberger, Leanne -A.555

Olson, Daniel -A.556, G.249

O’Neill, Kathleen - G.142

Ono, Yoko -A.557

Osborne, B.G. -A.557.100

Osuntokun, Keyede

Ouchi, Conrad -G.109

Oullet, Shelley -A.558, G.218.100

Ouellette, Kim -A.559

Oyawale, Christina -A.559.100

Oxenbury, Glen -G.174.200, G.310

Ozeri, Moshe - G.124, G.160, G.206, G.242.100, G.295

P

Painchaud, Dan -A.560

Paleczny, Catherine -A.561

Papp, Shannell B. -A.562

Park, Sora

Parker, Evan -A.121

Pashuk, Robert - A.354.100

Passmore, Heather -A.563

Patience, Alexandria -A.564

Patry, Réal -A.565

Patterson, Andrew James

Patterson, Jim -G.124.50

Patterson, Justin

Paul, Cassandra -A.487

Paulus-Maly, Jan -G.118

Pavka, Jeremy

Pearson, James -A.262

Pellerin, Lee Ann -A.566

Penny, Evan -A.567, A.568

Pepper, Gordon - G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Perkins, Marcia -A.569, G.198, G.252, G.252.1

Perreault, Carrie

Perron, Mireille -A.570, G.50, G.242.100, G.273, G.274, G.278

Peters, Ethan

Peterson, Stephen -G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Phelps, Stan -G.101

Philipsen, Neal -A.394

The Pidgin Collective

Pike, Bev -A.571, G.207

Pillar, Peter (Loys Egg) -A.572

Pink Flamingo

Pinter, Leslie -A.573

Piper, Danielle Elizabeth -A.573.5

Pisio, Lyle - G.263

Pitch, Marcia -A.574

Plimley, Paul -A.476

Poier, Grant -A.575, G.123, G.150, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.205, G.206, G.227, G.241, G.242.100,

G.257, G.257.1, G.257.2, G.278, G.295, G.312, G.312.1

Poitras, Edward -A.576, A.643, G.302

Pond -G.256

Pope, Laura -G.110

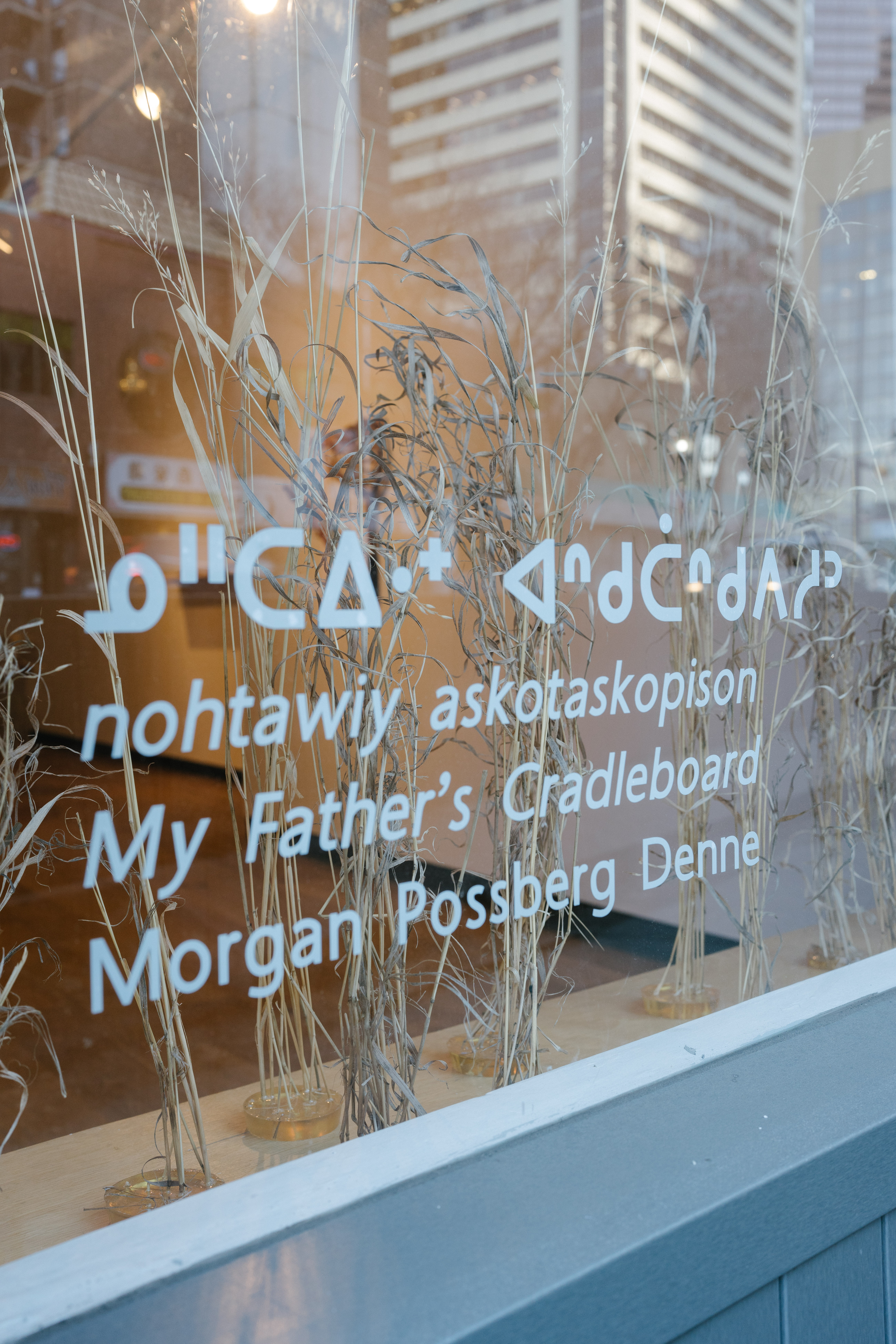

Possberg Denne, Morgan -A.576.5

Potter-Mael, Brigitte -A.577

Potts, Steve -A.422

Predika, Arion -A.578

Prent, Mark -G.113

Prentice, David -A.132

Priegert, Portia

Prize, Turner

Proskow, Deborah -A.354.100

Provost, Guillaume Adjutor

Ptak, Sylvia

Puchala, Diane - G.123.200

Puchala, Dolores - G.123.200

Puddle Popper

Puhach, Dan -G.118

Pura, Gregory -A.579

Paleczny, Catherine -A.561

Papp, Shannell B. -A.562

Park, Sora

Parker, Evan -A.121

Pashuk, Robert - A.354.100

Passmore, Heather -A.563

Patience, Alexandria -A.564

Patry, Réal -A.565

Patterson, Andrew James

Patterson, Jim -G.124.50

Patterson, Justin

Paul, Cassandra -A.487

Paulus-Maly, Jan -G.118

Pavka, Jeremy

Pearson, James -A.262

Pellerin, Lee Ann -A.566

Penny, Evan -A.567, A.568

Pepper, Gordon - G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2

Perkins, Marcia -A.569, G.198, G.252, G.252.1

Perreault, Carrie

Perron, Mireille -A.570, G.50, G.242.100, G.273, G.274, G.278

Peters, Ethan

Peterson, Stephen -G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Phelps, Stan -G.101

Philipsen, Neal -A.394

The Pidgin Collective

Pike, Bev -A.571, G.207

Pillar, Peter (Loys Egg) -A.572

Pink Flamingo

Pinter, Leslie -A.573

Piper, Danielle Elizabeth -A.573.5

Pisio, Lyle - G.263

Pitch, Marcia -A.574

Plimley, Paul -A.476

Poier, Grant -A.575, G.123, G.150, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198, G.205, G.206, G.227, G.241, G.242.100,

G.257, G.257.1, G.257.2, G.278, G.295, G.312, G.312.1

Poitras, Edward -A.576, A.643, G.302

Pond -G.256

Pope, Laura -G.110

Possberg Denne, Morgan -A.576.5

Potter-Mael, Brigitte -A.577

Potts, Steve -A.422

Predika, Arion -A.578

Prent, Mark -G.113

Prentice, David -A.132

Priegert, Portia

Prize, Turner

Proskow, Deborah -A.354.100

Provost, Guillaume Adjutor

Ptak, Sylvia

Puchala, Diane - G.123.200

Puchala, Dolores - G.123.200

Puddle Popper

Puhach, Dan -G.118

Pura, Gregory -A.579

Q

Querner, Andrew -A.580

R

Radul, Judy -A.581

Randolph, Jeanne

Raponi, Maria -A.582

Ratkay, Sonja

Rauscher, Colleen -A.583

Realica, Margaret

Rehman, Amin -A.583.50

Reid, Judy -G.118

Reid, Tony -A.474, G.129

Reimer, Julia -A.583.100

Reiter, Shawna -A.584

Renpenning, Robert -A.283, A.585, G.251

Rezaei, Mohammad -G.178.100

Riddle, Jeanie -A.585.100

Rimmer, David -A.585.200

Ris

Risk, Amy -A.586

Ritter, Celine

Rob, Bruce -A.587

Robert, Paul

Robertson, Clive -A.589, A.590, A.591, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Robertson, Diane -G.130

Robertson, Don - G.176

Robertson, Genevieve

Robertson, Mitch -A.592

Robertson, Valerie -G.165

Robinson, Spider -A.303

Robles, Paul -A.588

Rodger, Elsbeth -A.594

Rodgers, Bill -A.595, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198

Rodriguez, Pablo

Rogers, Honor Kever -A.597

Rogers, Lia -A.598

Rogers, Scott -A.593, A.596

Rojo Nuevo Collective -G.245, G.245.1

Rolfe, Nigel -A.599

Roneau, Brigitte -G.242.100

Ross, Bev -A.217

Ross, Will -A.600

Rothenberg, David -G.244, G.244.1

Rothlisberger, Mary -A.601

Rousseau, Chantal -A.602

Rowley, Rebecca -A.603

Roy, Annie -G.104

Ruschiensky, Carmen -A.605

Rushfeldt, Debra -A.604, G.117, G.118, G.119, G.134, G.216, G.277

Rusnak, Tanya -G.270, G.270.1

Russell, Charles -A.262.100

Rusted, Brian -G.206, G.273, G.274, G.295

Randolph, Jeanne

Raponi, Maria -A.582

Ratkay, Sonja

Rauscher, Colleen -A.583

Realica, Margaret

Rehman, Amin -A.583.50

Reid, Judy -G.118

Reid, Tony -A.474, G.129

Reimer, Julia -A.583.100

Reiter, Shawna -A.584

Renpenning, Robert -A.283, A.585, G.251

Rezaei, Mohammad -G.178.100

Riddle, Jeanie -A.585.100

Rimmer, David -A.585.200

Ris

Risk, Amy -A.586

Ritter, Celine

Rob, Bruce -A.587

Robert, Paul

Robertson, Clive -A.589, A.590, A.591, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102

Robertson, Diane -G.130

Robertson, Don - G.176

Robertson, Genevieve

Robertson, Mitch -A.592

Robertson, Valerie -G.165

Robinson, Spider -A.303

Robles, Paul -A.588

Rodger, Elsbeth -A.594

Rodgers, Bill -A.595, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.198

Rodriguez, Pablo

Rogers, Honor Kever -A.597

Rogers, Lia -A.598

Rogers, Scott -A.593, A.596

Rojo Nuevo Collective -G.245, G.245.1

Rolfe, Nigel -A.599

Roneau, Brigitte -G.242.100

Ross, Bev -A.217

Ross, Will -A.600

Rothenberg, David -G.244, G.244.1

Rothlisberger, Mary -A.601

Rousseau, Chantal -A.602

Rowley, Rebecca -A.603

Roy, Annie -G.104

Ruschiensky, Carmen -A.605

Rushfeldt, Debra -A.604, G.117, G.118, G.119, G.134, G.216, G.277

Rusnak, Tanya -G.270, G.270.1

Russell, Charles -A.262.100

Rusted, Brian -G.206, G.273, G.274, G.295

S

Saar, Allison -A.606

SAD LTD

Saldana, Zöe Sheehan -G.256

Salzl, Tammy

Sampson, Leslie - G.204.100

Sasaki, Jon -A.607

Sato, Teak -G.278

Saucier, Robert -A.607.100

Saunders, Zachary -A.190

Sauvé, Eric

Savage-Hughes, Carlan

Savage, Uii

Sawatsky-Cariou, Sandra -G.118

Sawyer, Carol -A.608

Schäffler, Edith -G.114

Schein, David -A.309

Schick, Cathy (Cat) -A.609, A.609.1

Schmid Esler, Annmarie -A.133, A.610, G.163, G.165

Schmuki, Jeff -G.212

Schoenberg, Alice

Schofield, Stephen -A.612

Schoppel, Amanda -A.613, G.256.100

Schraenen, Guy -A.614

Schulz, Lynne -G.265

Scott, Mary -G.163, G.278, G.314

Scott, Ryan McClure

Sebelius, Helen -A.225, A.615, G.101, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.163, G.165, G.252, G.252.1, G.257, G.257.1

Semple, Glen -A.616, A.617, G.198, G.286

Senini, Blake -A.251, G.162.100, G.162.101, G.162.102, G.205, G.205.1, G.205.2, G.257, G.257.1 Sepúlveda, Dámarys -G.245, G.245.1

Shahab, Alia -G.178.100

Shatzky, Melanie -A.618

Shaw, Christine -A.619, G.208.200

Shecky Formé - G.121.100

The Shell Projects -A.619.5

Sherlock, Diana -G.244, G.244.1, G.242.100, G.278

Shikitani, Gerry -A.620

Shimamoto, Shozo -A.621

Shin, TJ

Shindelman, Marni -A.427

Shortt, Stephen -A.622

Sidarous, Celia Perrin

Sidorowicz, Anetta -G.102

Siebens, Evann -A.246.100

Simmonds, Wright -A.623

Simpson, Gregg -A.216.100, G.191

Sinotte, Michelle -A.624

Sitcomm

Skelton, Carl -A.625

Slams, Zac

Sleziak, Zofia -A.626

Slopek, Edward Renouf -A.627, G.234, G.273

Sloten, Sarah van

Smibert, Evan -G.100, G.178.100

Smith, Clint Adam

Smith, Jason B. -A.586

Smith, Leo -A.628

Smith, Rosemary

Smith, Whitney -A.207

SMOLinski, Richard -A.629, G.149

Smylie, Barry -A.500, G.108.100, G.114.100, G.124.50, G.124.100

Snow, John -A.630, G.222

Snow, Michael -A.631, A.636, G.113

Snowden, Mike -A.632

Snyder, Achim -A.611

Snyder, Brett -G.110

Snyder, Nikko -A.615

Soerensen, William -A.633

Sokol, Casey -A.634

Somers, Sandi -A.224, G.158

Sorell, Lindsay -A.634.1

Sosnowski, Kasia -A.440