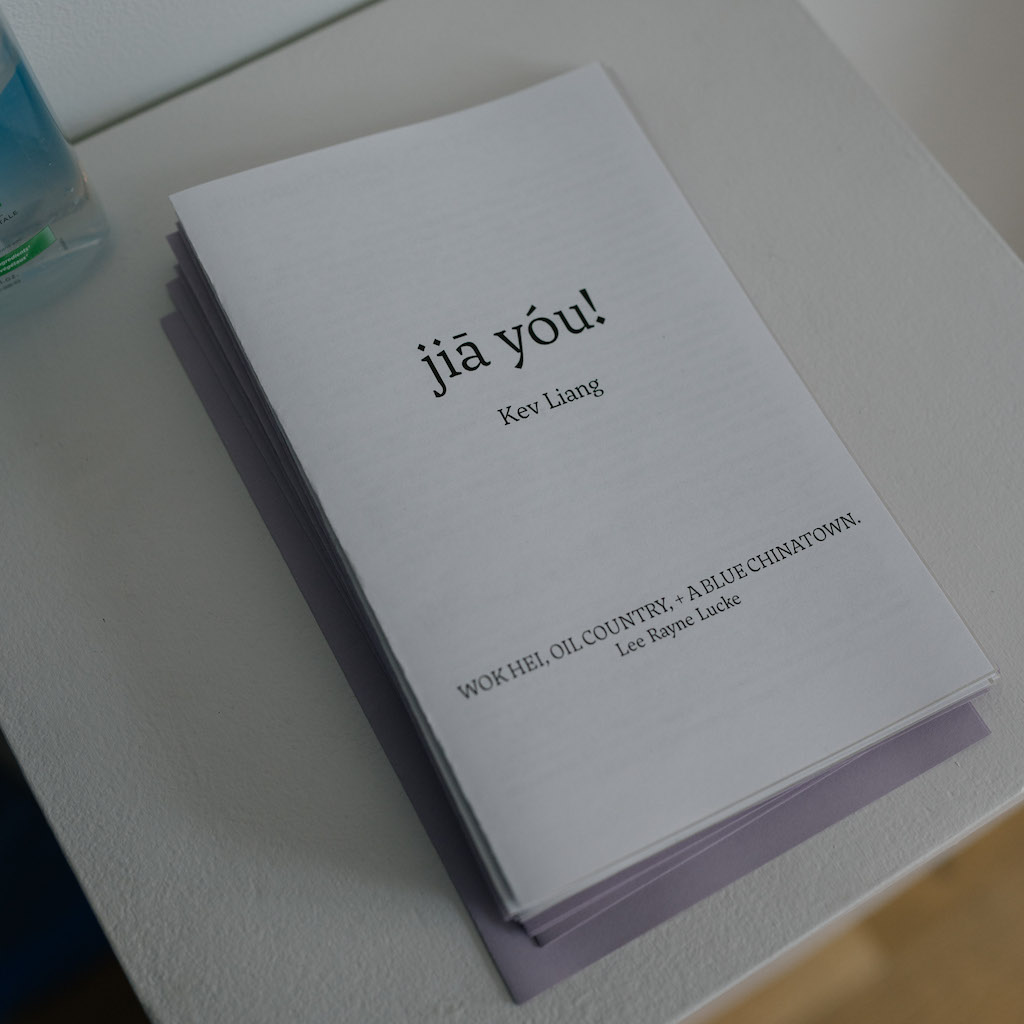

jiā yóu!

Kev Liang

January 26 - March 9, 2024

Opening Reception:

January 27th, 2024

7-9PM

@ The New Gallery

Through lens-based processes, I create multimedia narratives that utilizes print-media as well as digital media, put into a contextual space that encapsulates the existential anxieties within my homo/queer, diasporic, 2nd-generation Chinese-Canadian identity and perspective in the Anthropocene. Drifting through fast-paced urban time and space after growing up in a secluded and rural environment, I attempt to dissect the different cultural and philosophical aspects of my identity or being as a means to try and understand why I have such existential fears. Using print-based repetition of food-related emblems such as rice bowls, chopsticks, and gritty family-owned woks alongside long-lasting yet ephemeral synthetic materiality of the tarps, I reflect on the incessant act of self-digestion while also finding alternative modes of care and resistance as a homo/queer body when it comes to fighting blood-related angst. By taking into consideration the traditional, cultural, and philosophical Chinese expectation of continuing your blood lineage and my inability to do so as a queer body, as well as the idea of Chinese Canadian immigrants relying on labor and prosperity as a means of survival and presence, I ask myself and others: How much is at stake in terms of ensuring a long term presence or settled lineage for homo/queer and diasporic identities like myself? How can I, or will I ever, find my own sense of kinship or family? Where do individuals like myself lie within an incredibly labor and wealth oriented society?

Documentation by Danny Luong

WOK HEI, OIL COUNTRY, + A BLUE CHINATOWN

Essay by Lee Rayne Lucke

WOK HEI LABOUR

I first met Kev Liang around a round table of food in a Chinese restaurant. Over the time that we’ve connected, I learned that Kev grew up in Trochu, a small town in Alberta near Calgary. Kev’s parents’ Chinese restaurant, Peking Cafe, was the Chinatown for the town Kev grew up in. Like how Chinatowns begin, Kev’s family restaurant was a means to make a living. The Chinese restaurant is typically an acceptable form of labour for new Chinese immigrants. Early Chinese settlers, usually men, were turned away from jobs that competed with Whites and so, were pushed into feminized forms of labour like cooking and laundry. Since their early arrival, Asian men have been emasculated in Western culture. They are portrayed as weak, effeminate, and lacking masculinity, perpetuating harmful stereotypes that contribute to discrimination and racism against the Asian community.

Listening to the sounds of the frying wok in Kev’s artwork installation titled jiā yóu!, I think about how I often hear children of Asian immigrants share about how their parents' way to show love is with food. In Chinese culture, to say hello, we ask: “have you eaten yet?” "chī le ma?". Bowls of cut fruit, hand wrapped dumplings, broths simmering for hours are part of these stories. It is not part of our parents' culture to say, “I love you”. Our parents show love, practicing the belief that actions speak louder than words. Kev told me that his parents said their children will never go hungry because of their restaurant. Kev’s dad might say restaurant work is poor labour, and at the same time the restaurant is a labour of love for his children.

RED THE COLOUR OF HAPPINESS

Kev and I are dressed in red. It's the lunar new year and we’re sitting in a circle around a large round table with artists who are also dressed in red. We’re eating Chinese new year foods that traditionally symbolize good luck. Much like how many of us are dressed in red for the new year, Chinatowns in our cities are recognized for being decorated in red. A celebratory colour, red represents happiness. Many Chinatowns are recognized in their cities for red street lamps, red gates, red signs, and red lanterns. Red isn’t the only symbolic colour in Chinese culture, but looking at our Chinatowns it would be fair to say that red is one of the most important colours in Chinese culture.

BLUE THE COLOUR OF GRIEF

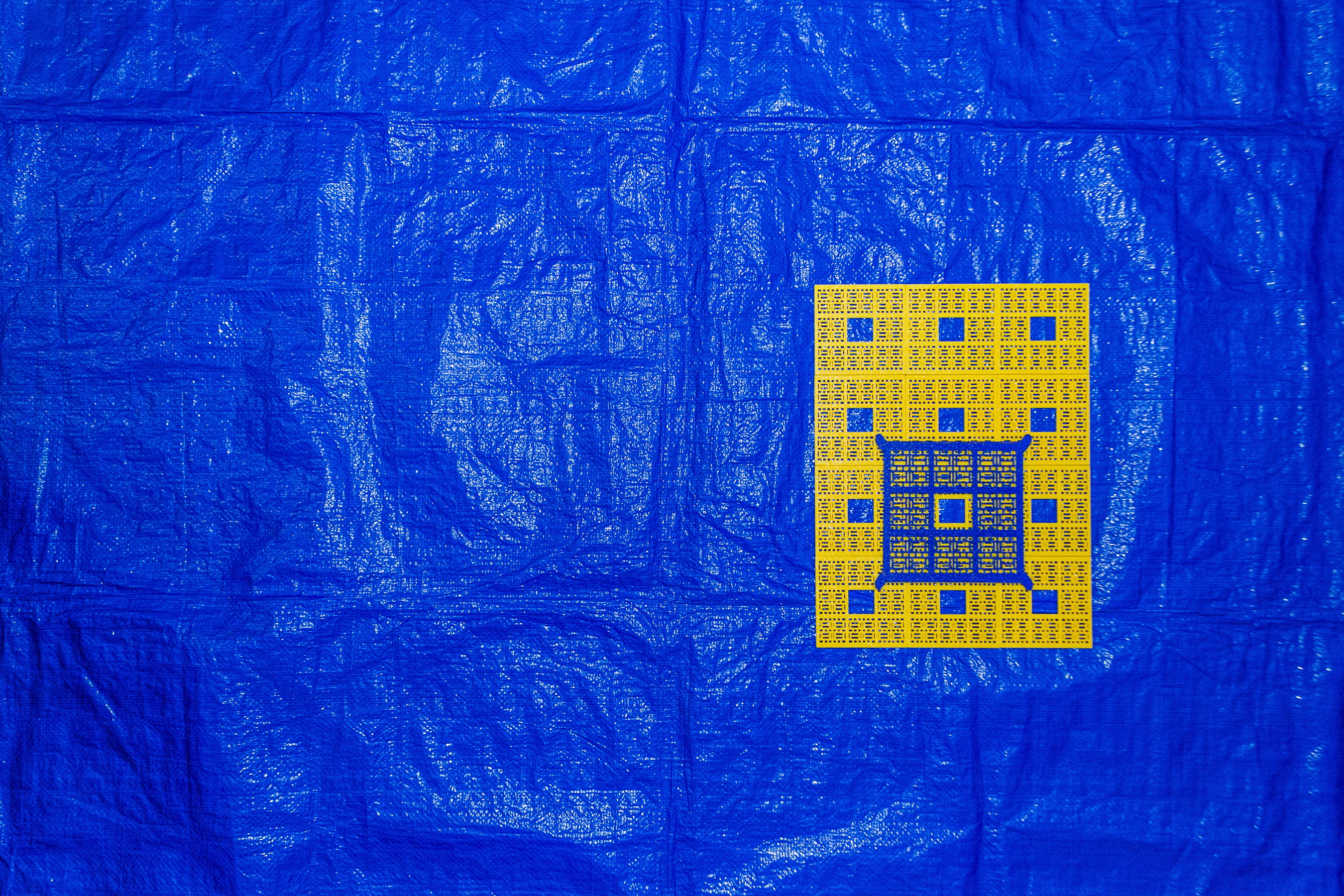

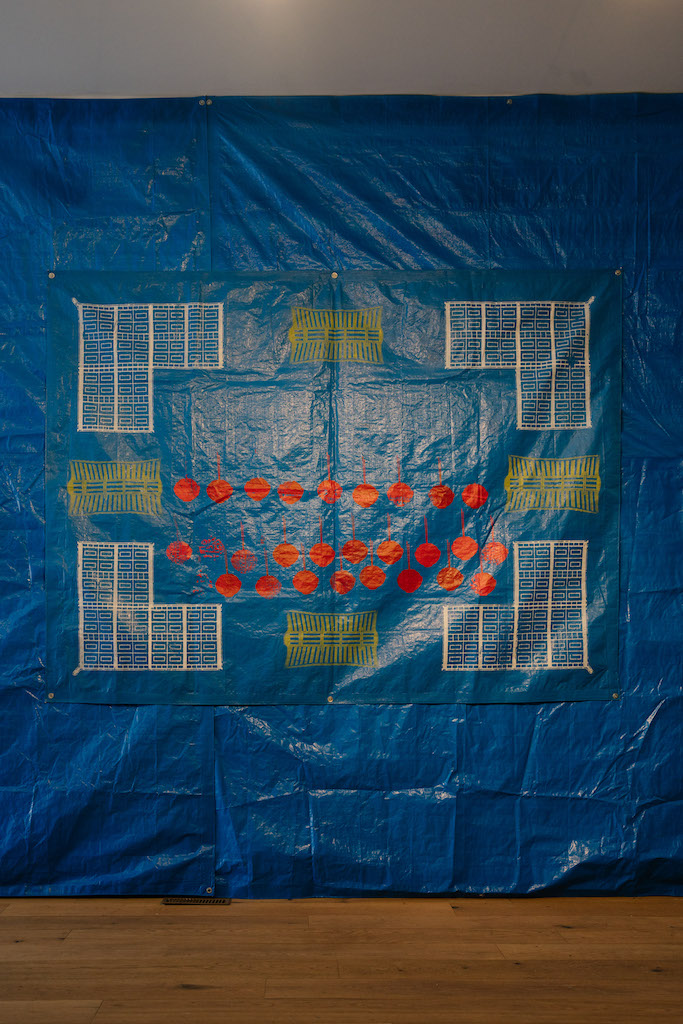

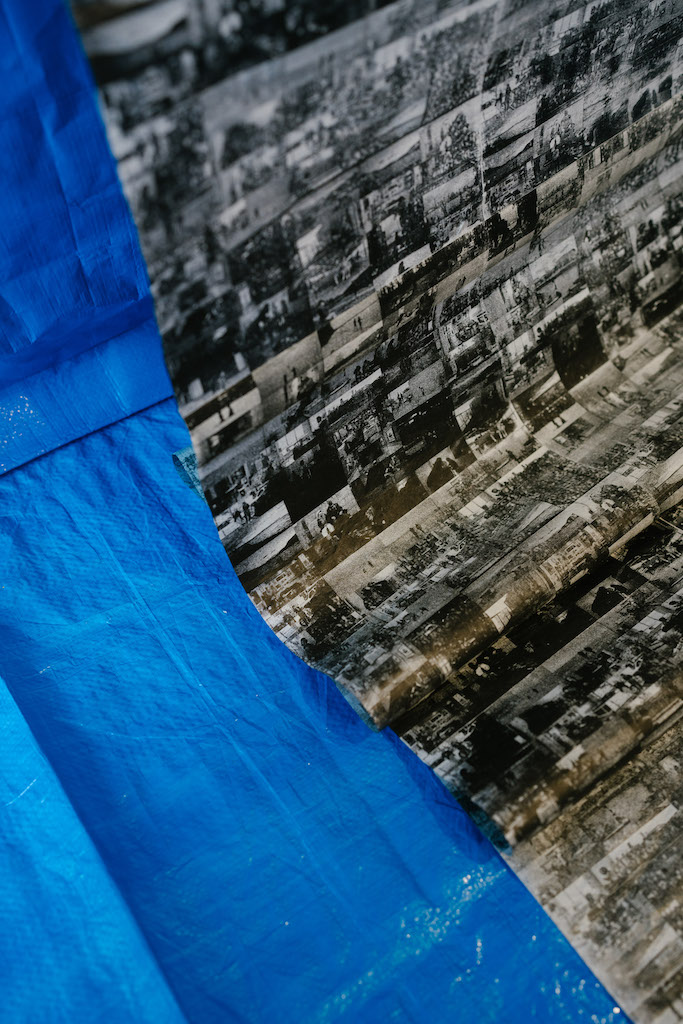

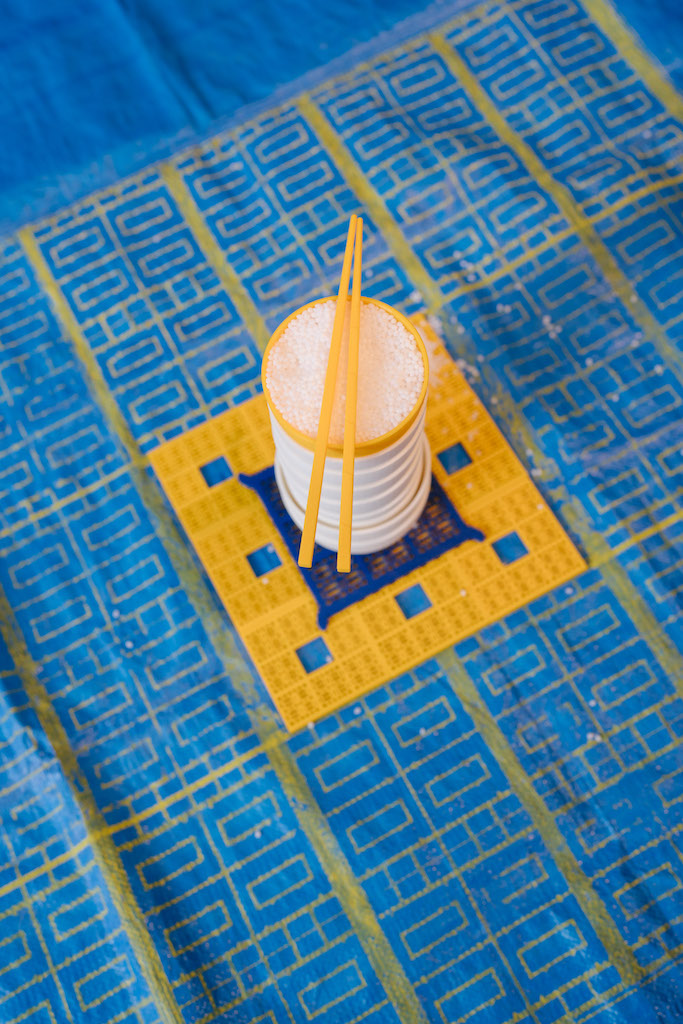

In “jiā yóu!” Kev's Chinatown is blue. The gallery walls are covered in blue tarps. On the tarps are repeating white and yellow silk screened images of abstracted Chinatown gateway architecture taken from Edmonton as well as Vancouver. This Chinatown aesthetic which is widely recognized in many Chinatowns all over the world, is schematized and made modular so that the repetition looks exact and linear, speaking to ideas of mass production. Chinatowns throughout the world use this self-orientalizing aesthetic as a form of protection.

Entering the installation, it’s like looking at a cross section of Kev’s internal experience of the Chinatown he grew up in that is intimately tied to his family. What we’re taught to hide on the inside as children of immigrants, the artist reveals. As second generation, we are taught to hide and contain the complicated and sometimes painful diasporic experience of disconnection that comes into a cultural clash with the elders in our families and in our Chinatowns as well as a dissonance with the majority white world we live in. We don’t have a lot of immediate signifiers of belonging, especially in small towns. Kev Liang externalizes these feelings in material with the colour blue, a colour that isn’t immediately associated with Chinese culture, yet still holds its own symbolism within the culture. Here the artist uses the blue colour in a way that western culture immediately understands it: blue is the colour of grief and the colour of masculinity in the gender binary construct. The artist processes the dominant narratives and expectations placed upon him by his parents and society with the colour blue: to be a man, and to be valued as a man means having success, having wealth, being married to a woman, having children, and on top of all that: tall and strong. These are the dreams Kev’s parents have for him. These dreams that are tied to status are signs that many immigrant parents recognize as safety. A lot of people are trained to believe that the epitome of love is controlling somebody into safety. Stability and normalcy offer a sense of peace and security for our immigrant parents. It validates the painful experience of immigration. However, not often understood by our elders is that these dreams are tied to dominant systems that historically have overlooked and oppressed queer and racialized bodies. These are dreams that Kev cannot fulfill for his parents, there is a guilty agony tied to this blue yet a resistance is interwoven between the layers of polyethylene.

LIVING IN OIL COUNTRY

The blue tarp made of polyethylene or polypropylene is the material of oil, the resource most notably tied to the economy and the identity of Alberta. In Edmonton, the city Kev is now based in, the hockey team is named the Oilers. The team’s name was chosen because Alberta is the center of Canada’s petroleum industry. During the 2006 playoff run, the “This is Oil Country’ sign hung in the arena’s rafters above the crowds. Here, resource extraction is tied inextricably into culture. Here oil is a way of life. Even if Kev and I don’t identify with that type of “oil country” person, the type that spray paints “This is oil country” over a mural of climate activist Greta Thunberg; and even if you are not an Albertan, oil is at the center of our lives. Globally, oil is ubiquitous; it is in everything, it is how we move in our cars and planes, and it is used to make the houses we live in. The oil of the tarp is the material that structures and contains the “restaurant” in the gallery, a part of the representation of the home where the artist, Kev, was raised in.

YELLOW THE COLOUR OF RESISTANCE

jiā yóu!: Directly translated jiā means add and yóu means “oil”. jiā yóu' is the Mandarin romanization and “ga yau” is the Cantonese romanization. A common Chinese saying to encourage, the expression originates as a cheer in the 1960s at the Macau Grand Prix used to imply stepping harder on the gas pedal and metaphorically adding more fuel to the tank. In the 2019-20 Hong Kong protests, ga yau became the rallying cry used for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, with the colour yellow becoming synonymous with the movement. In Hong Kong, yellow ribbons adorn railings and trees in public spaces; individuals wear yellow ribbons to show support; and a yellow economic circle, a form of consumer activism that classifies businesses based on their support or opposition to the protests, has been built.

I see Kev’s own yellow spirit of self-determination punctuated in the installation. Notably, a square of yellow Chinese motifs surround a plastic stack of bowls with a full bowl of rice and chopsticks. In Chinese culture, it is taboo to stick chopsticks straight up in a bowl of rice because it mimics the incense offered to ancestors. Playing with this superstition, Kev resists the narratives and expectations that are placed upon him by society. It’s a way to kindly express: “Thank you for involving me, but it’s best if I refrain from participating.”

ALBERTA MORNING with Kev Liang

Kev Liang joins CKUA's Grant Stovel to discuss jiā yóu! and his identity as a queer, diasporic 2nd-generation Chinese-Canadian.

Kev Liang is an emerging artist based in Edmonton, Treaty 6 territory, with a BFA in Printmaking and Intermedia with Distinction from the University of Alberta. Kev has exhibited at SNAP Gallery, Latitude 53, Art Museum at the University of Toronto for the 2021 BMO 1st! Art award, and more, with an upcoming solo exhibition opening at Calgary’s The New Gallery in January 2024. He tackles his homo/queer, diasporic 2nd-gen Chinese-Canadian identity and its existential anxieties of lineage and prosperity within the Anthropocene. Kev was a Production Assistant for The Works International Visual Arts Society, a Gallery Intern for Latitude 53, as well as a Gallery Attendant for Ociciwan Contemporary Art Centre. Recently, he has been interested and involved in community-based artistic projects concerning Edmonton’s Chinatown such as Chinatown Greetings and AIYA Collective and will continue to seek opportunities to contribute towards our own communities as well as expand artistically elsewhere.

Lee Rayne Lucke is an artist, community organizer and cultural worker. Their work addresses issues of spatial justice in order to call attention, mobilize, or divert structures of power with collective artistic gestures and participatory processes. Together with an artist and Chinatown community group called aiya哎呀, they offer spaces to remember the emotional and geographic loss of amiskwacîwâskahikan’s Chinatown at its intersections. Through the lens of Chinatown, the work is postured to envision and practice better ways of being in the city. The work spans public interventions, satirical performance, capacity building with anti-oppression workshops such as “still in chinatown on indigenous land working space for artists and cultural workers”, organizing to form openings for better futures, and making social spaces of cultural care.

https://youtu.be/Za75TWGlUc4

https://youtu.be/YfMRRzefzwM

中文翻译 Chinese Translation ...