Main Space Exhibition /

careworn & coil

Christina Oyawale

November 1 – December 19, 2024

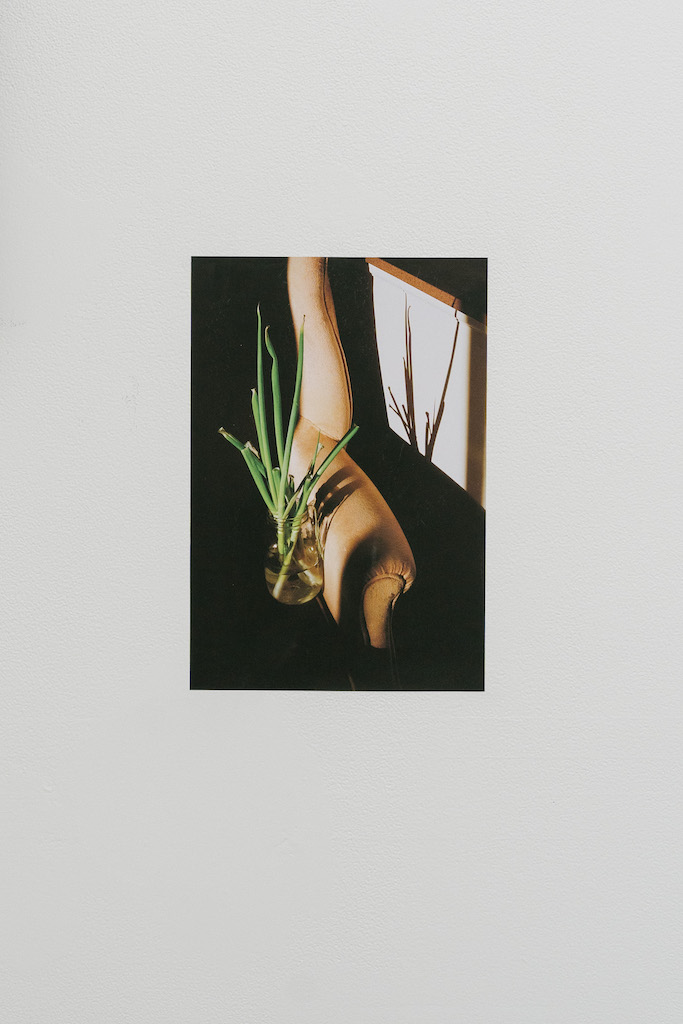

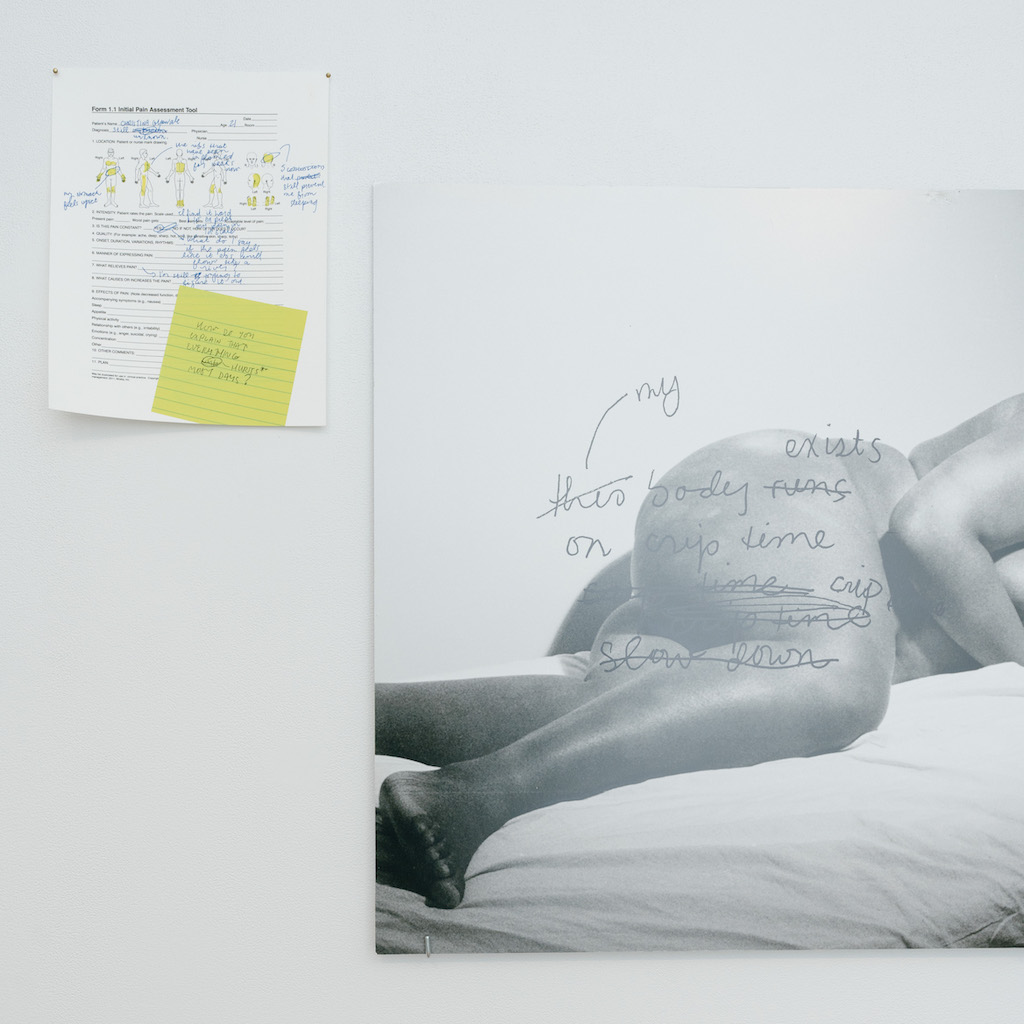

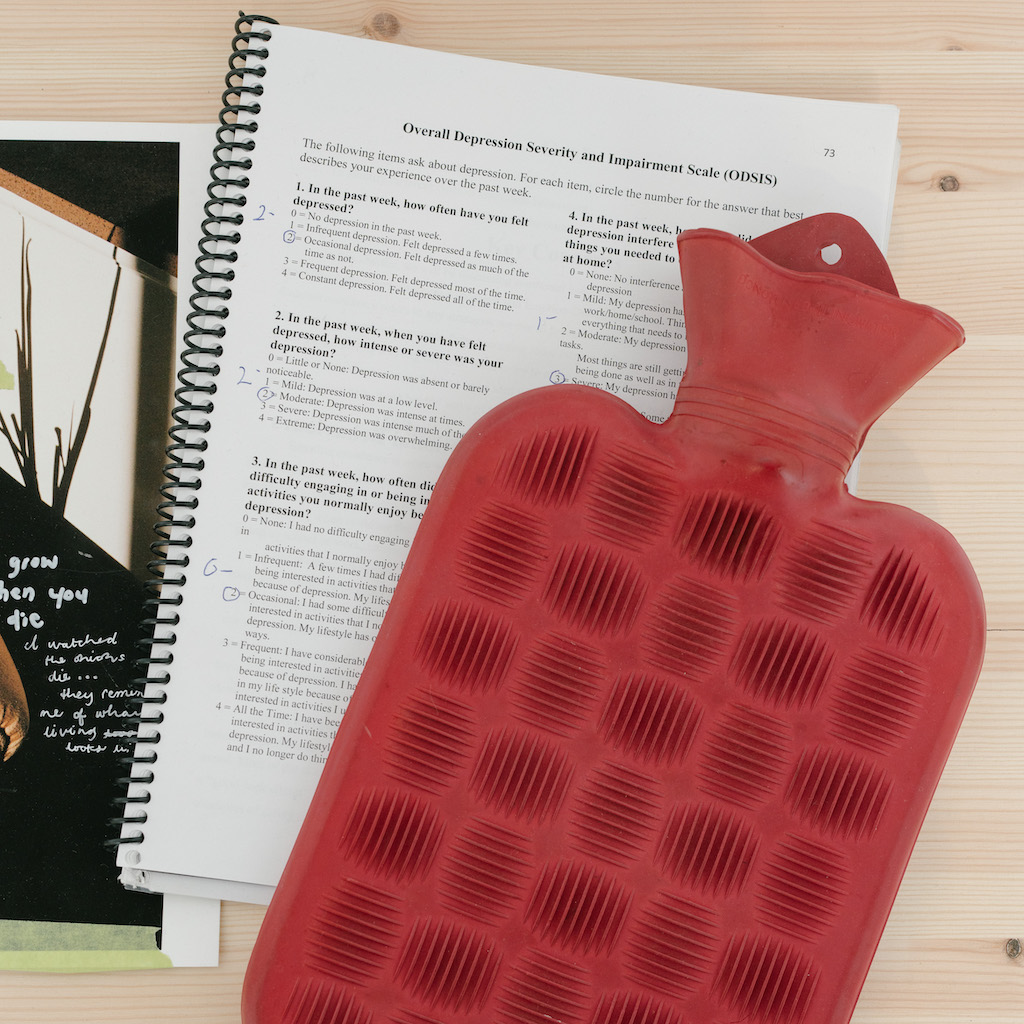

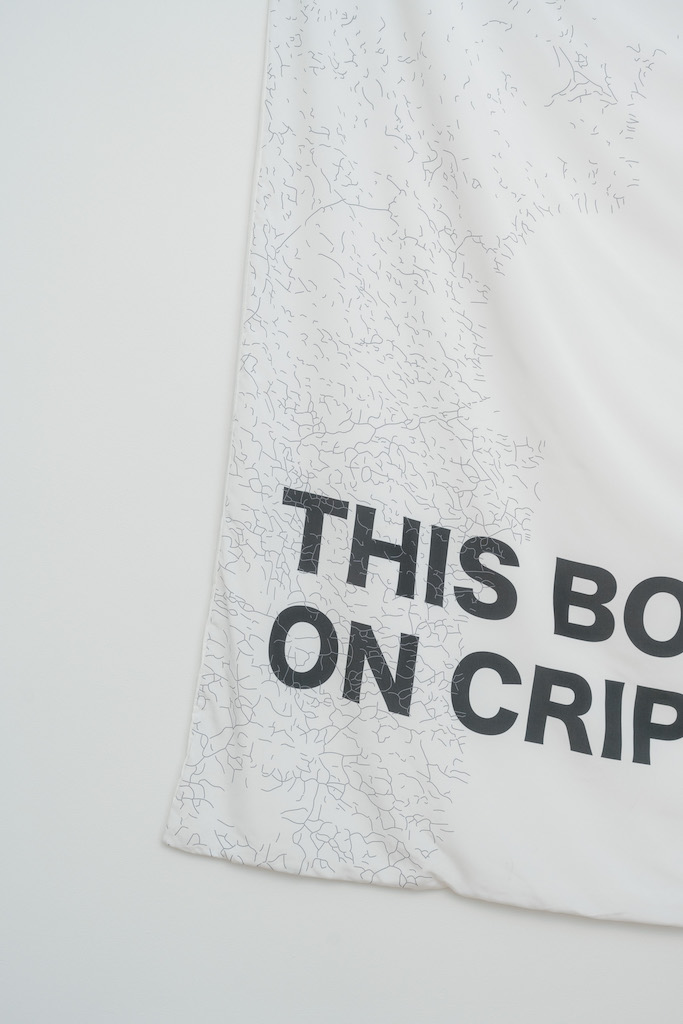

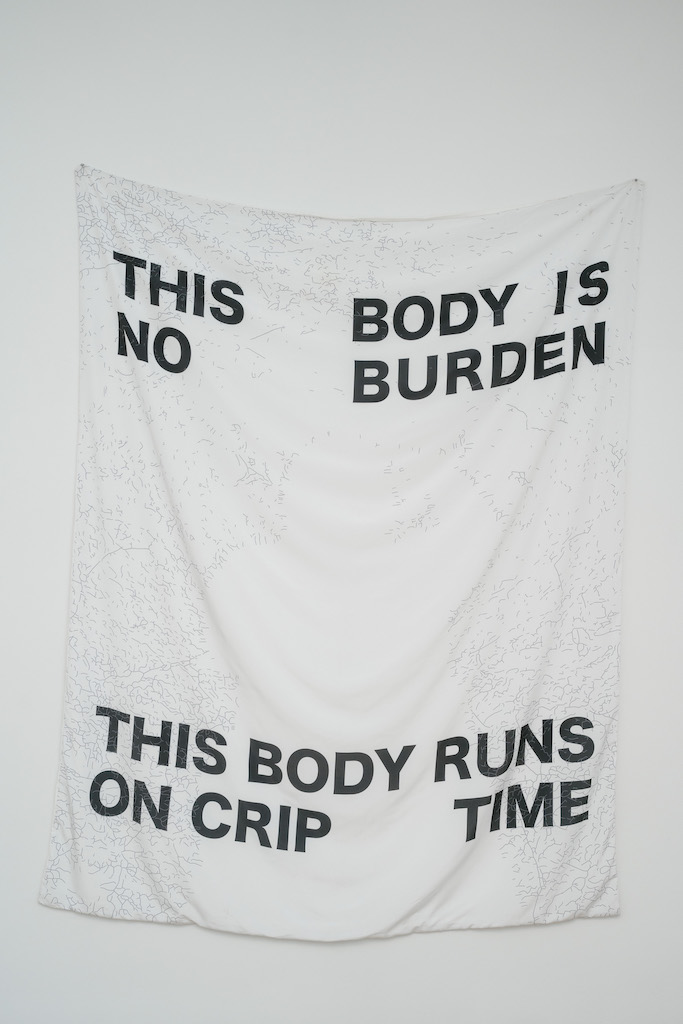

My body moves on crip time, meaning, it decides when it wants to move, it decides when I need to slow down and when it’s time to go. I experience space and time in a completely different way than most do. I’ve learned to live through the discomfort, but this is my attempt at being vulnerable with you. Let’s reevaluate our perceptions of private versus public life. I want you to understand that it’s not pretty, it’s raw and it’s ugly. In the words of Mia Mingus, I would rather be “ugly—magnificently ugly” than “beautiful” because I am flawed and sometimes need the space to remember that. I move on crip time, as breathing hurts from my ribs that have been inflamed for weeks. I move on crip time because I am too anxious to face the world today. So I stay in my space until I feel it is time to leave.

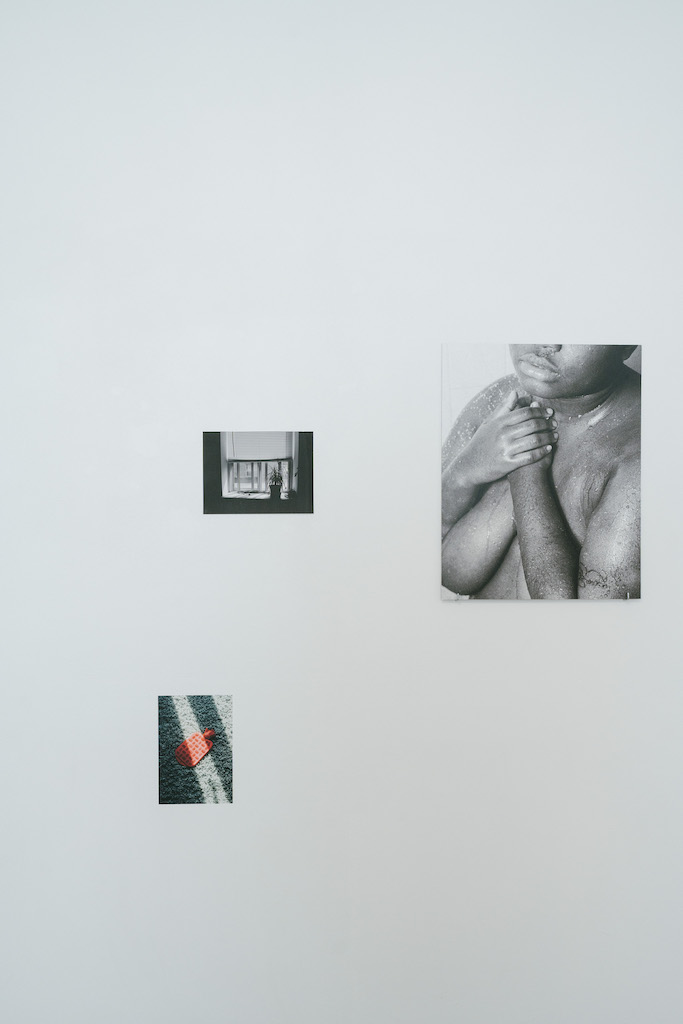

I watch the seasons change from my window, I watch the sun kiss my pigmented skin.

I've built my world for you, I’ve reconstructed my space.

I watch the seasons change from my window, I watch the sun kiss my pigmented skin.

I've built my world for you, I’ve reconstructed my space.

– Christina Oyawale

Documentation by Danny Luong

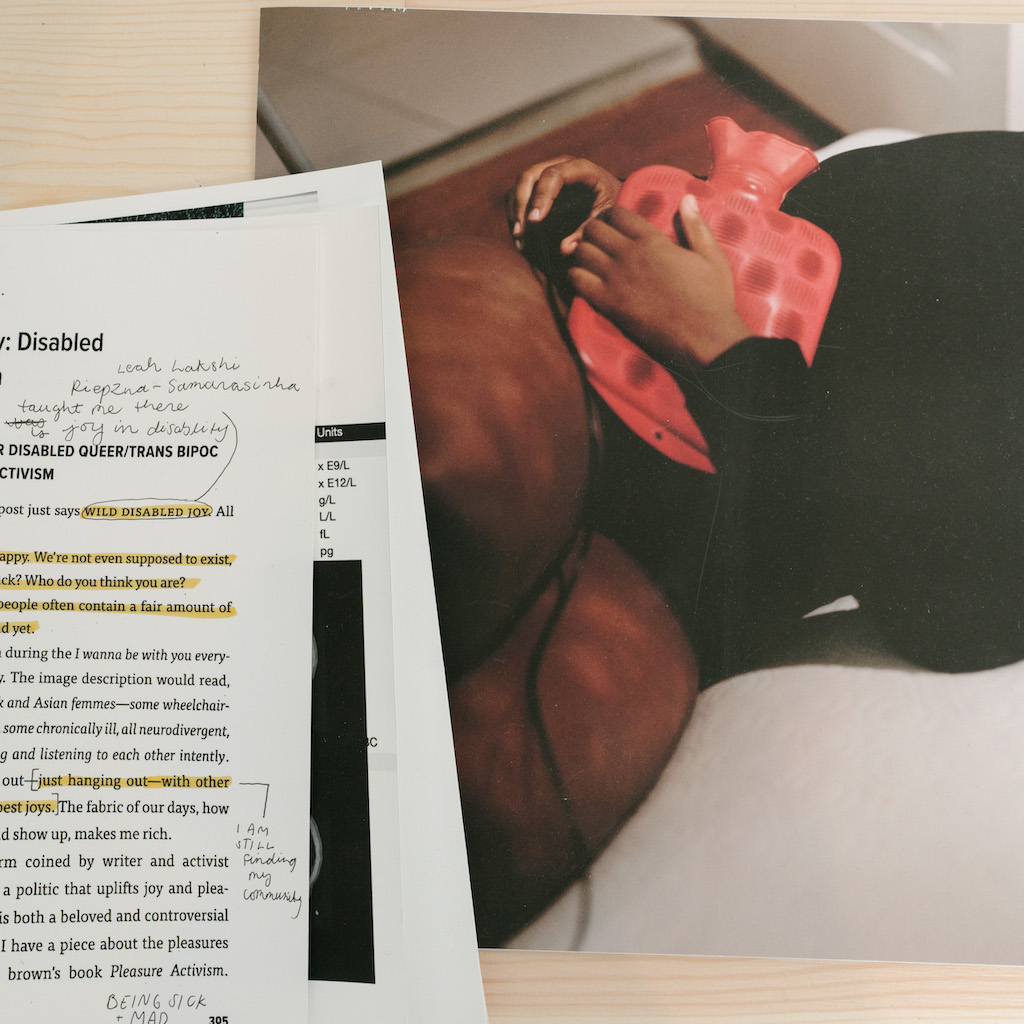

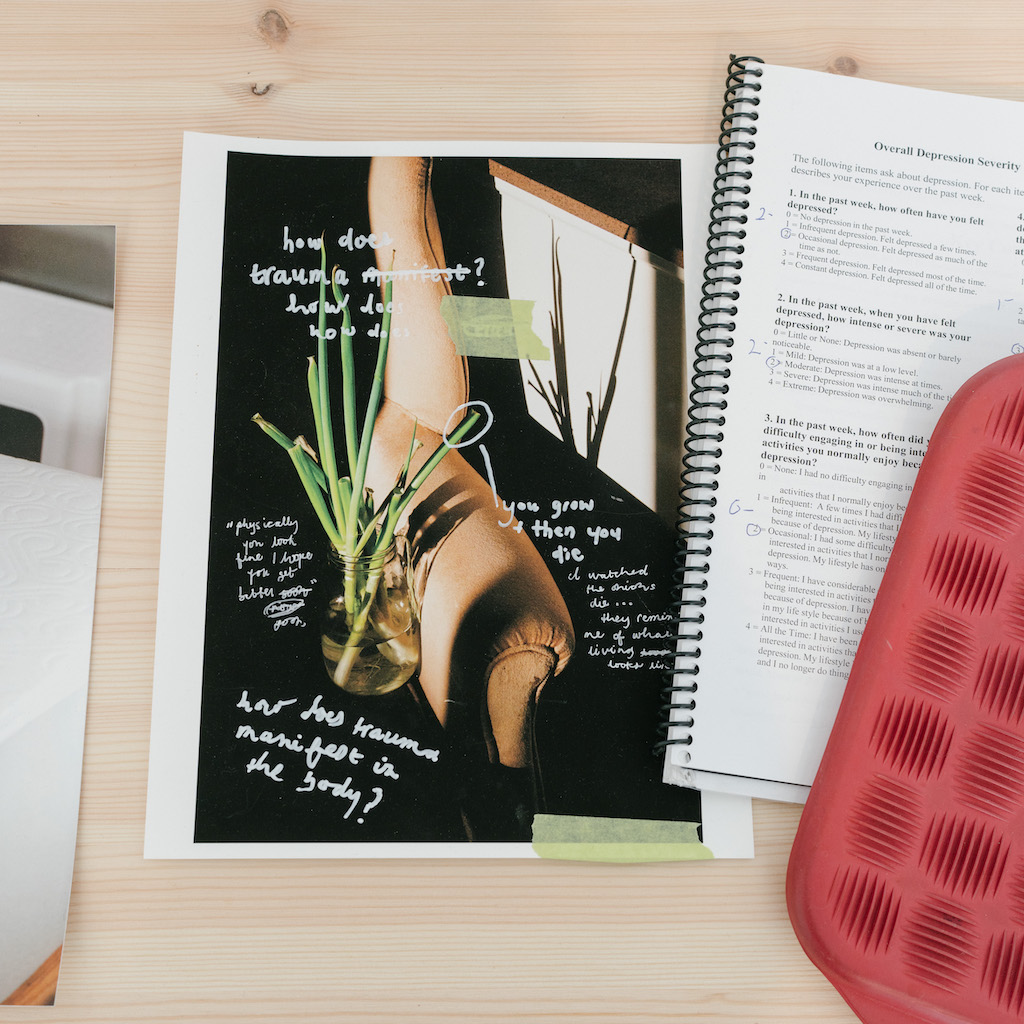

careworn & coil undertakes the ongoing photographic and written documentation of my disabled body through invisible physical and mental illness. The project aims to showcase the daily negotiations that occur within myself, replicating the complexities and comfort of living as a spoonie. I work to challenge notions of able-bodied productivity, using photographs and sculptural installation to task viewers with challenging their perceptions of the human experience, creating an environment that emphasizes the emotional vulnerability of placing private life into the public sphere. careworn & coil breathes the concept of "Crip Time", a term coined by academic Alison Kafer – disabled people’s relationship to time rather than monoculture’s ideas productivity in a given day – and bell hooks’ “Oppositional Gaze” – allowing Black bodies the right to “looking”. The project asks viewers to interrogate their perceptions of invisible illness and how it manifests in the body. Within the images, light and shadows act as a catalyst for both these theoretical concepts and how they specifically interact with my navigation of fatness, depression and chronic pain.

The project applies research-creation as a means of situating itself within the broader conversation of disability theory; notably from a Black Feminist disability politic that is oftentimes understudied. Incorporating the works of racialized disabled scholars such as Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Mia Mingus and Alice Wong allows me to take hold of my personhood while rejecting palatability. Ultimately, in staking myself on these terms, I allow for an active viewership that challenges ableism and supposedly “correct” ways of being consumed.

The project applies research-creation as a means of situating itself within the broader conversation of disability theory; notably from a Black Feminist disability politic that is oftentimes understudied. Incorporating the works of racialized disabled scholars such as Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Mia Mingus and Alice Wong allows me to take hold of my personhood while rejecting palatability. Ultimately, in staking myself on these terms, I allow for an active viewership that challenges ableism and supposedly “correct” ways of being consumed.

Seeing you, seeing me: notes on Black crip kinship

by Sarah-Tai Black

“We must leave evidence. Evidence that we were here, that we existed, that we survived and loved and ached. Evidence of the wholeness we never felt and the immense sense of fullness we gave to each other. Evidence of who we were, who we thought we were, who we never should have been. Evidence for each other that there are other ways to live — past survival; past isolation.”

— Mia Mingus

There is something divine that happens when we are able to commune together to give testimony and bear witness to our realities as Black crip folks. It isn’t simply the neoliberal machinations of representation or a reductive identity politics at work, but a form of access intimacy given further specificity (that is, care) through the experience of living as disabled and chronically ill people in an anti-Black world.

It is a form of Black crip kinship that recognizes the ways in which Black lives are expected to endure the expectation of supposed futurelessness; the ways that our current world’s privileging of able-bodied experience precludes access to space, relations, and supports, in turn, further compounding this deathbound assumption of Black life, rather than wholly reorienting it (as it often does for non-Black crip folks).

But we know this. It is in the safety of care for the context of our daily lives — offered without being bound to the labour of legibility — that this space of kinship, whether that be literal space, virtual space, or otherwise, can be cultivated and stewarded. Even if sometimes all too fleeting, this feeling of communion with other Black crip bodyminds expands the bounds of our current space and time to encompass multiple worlds and, hopefully, future models of possibility.

Here, access needs (and desires) are no longer an accommodation but an understood necessity; disability is no longer invisibilized or made to answer to the white supremacist call to undoubtedly name oneself and present a meticulously documented archive of diagnosis and condition as so-called proof; being in relation to one another no longers comes with the demand to centers ableist comforts, but considered effort to collectively safeguard and offer our bodies and minds to be just as they need to be in that moment.

For many of us, spaces like the ones offered by the work of Careworn & Coil are few and far in between, offering a buoy upon which we are offered rest and refuge alongside those who have experienced and been oriented in the world likewise. They are an invitation to name and welcome our vulnerabilities with grace, to share the often enigmatic nature of what our bodies know and how they come to know it, to release the expectation of not just action or productivity, but the emotional labour of performing being “well” (or perhaps, more truthfully, just “okay”) as a form of survival in a world structured by, not just ableism, but anti-Black respectability politics.

Here, the act of looking is one that relocates our experiences — so often these aspects of Black crip life we know for certain but are continuously asked to deny or neglect — from the made-private to the public. This defiant looking radically bends time — cripping time — protracting it into a more fully prismatic expression of our experience as it is often reshaped and reformed by our bodyminds in what feels like a multiplicity of moments at once.

It’s an act of recognition that opposes our current world’s violent desire to not only negate our individual and collective experiences, but also to disavow us, structurally and spiritually, of our interdependence. It is a sterling reminder that we are able to find life sustaining kinship in such acts of seeing and being seen, in all ways and by all means. As our Black crip ancestors did, as we do, as our futures must: we exist together, past survival, past isolation.

Christina Oyawale (b. 2000 Toronto; lives and works in Toronto and Winnipeg) is a self-proclaimed “anarchist punk boy” and emerging multi-hyphenate artist, graphic designer, researcher + curator. Working with film, photography and text, they use memories, shared Black feminist history and knowledge exchange in order to create work that emphasises curiosity of learning and documenting the necessity of slowness. Currently they are attempting to break free from the expected/frequent uses of identity politics under our current neo-liberalist society, that requires marginalized people to sell their identity in exchange for “visibility” in the art world and academia.

Their work and research attempts to foster communal conversation surrounding capitalism, anti-Black racism, queer-/trans-phobia and ableism. Many of these socio-political conditions that they believe we should be fighting to dismantle. Their current research interests and musings surround: Social Reproduction Theory, the works of Angela Davis, Naomi Klein and Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, queer USSR and Black feminist disability theory.

Sarah-Tai Black (they/them) is an arts worker, curator, and critic born and (mostly) raised in Treaty 13 Territory/Toronto whose work aims to center Black, queer, trans, and crip futurities and freedom work. Their curatorial work has been staged at Cambridge Art Galleries (Cambridge, ON), Dunlop Art Gallery (Regina, SK), MOCA (Toronto ON), PAVED Arts (Saskatoon, SK), and A Space Gallery (Toronto, ON) and they have worked in public arts spaces such as Art Museum at the University of Toronto, McMaster Museum of Art, and as Interim Artistic Director of Paved Arts.

Their work and research attempts to foster communal conversation surrounding capitalism, anti-Black racism, queer-/trans-phobia and ableism. Many of these socio-political conditions that they believe we should be fighting to dismantle. Their current research interests and musings surround: Social Reproduction Theory, the works of Angela Davis, Naomi Klein and Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, queer USSR and Black feminist disability theory.

Sarah-Tai Black (they/them) is an arts worker, curator, and critic born and (mostly) raised in Treaty 13 Territory/Toronto whose work aims to center Black, queer, trans, and crip futurities and freedom work. Their curatorial work has been staged at Cambridge Art Galleries (Cambridge, ON), Dunlop Art Gallery (Regina, SK), MOCA (Toronto ON), PAVED Arts (Saskatoon, SK), and A Space Gallery (Toronto, ON) and they have worked in public arts spaces such as Art Museum at the University of Toronto, McMaster Museum of Art, and as Interim Artistic Director of Paved Arts.

Glossary:

Crip - a word reclaimed by the disabled community that can be used as a noun, adjective, or verb to refer to disabled people; see also, crip theory.Bodymind - a term used in disability and feminist studies to describe the idea that the body and mind are interdependent and cannot be separated.

Spoons/Spoonie - Spoon theory is a metaphor describing the amount of physical or mental energy that a person has available for daily activities and tasks, and how it can become limited. The term was coined in a 2003 essay by American writer Christine Miserandino. Those with chronic illness or pain have reported feelings of difference and alienation from people without disabilities. This theory and the claiming of the term spoonie is utilized to build communities for those with chronic illness that can support each other.

中文翻譯 (Chinese Translation)

看到你,看到我:關於黑人殘障親屬關系的筆記

“我們必須留下證據。表明我們曾經在這裏的證據,我們曾經存在,我們曾經幸存、愛過並感受過痛苦。證據表明我們從未感受到完整,以及我們彼此給予的深刻的充實感。證據證明我們誰,我們曾以為自己是誰,以及我們不該成為誰。為彼此留下證據,表明存在其他生活方式——超越幸存;超越孤立。”— Mia Mingus

當我們能夠共同交流、並見證作為黑人殘障人士的現實時,有壹種神聖的東西在發生。這不僅僅是新自由主義的表述機制或還原身份政治在起作用,而是壹種通過在壹個反黑人的世界中作為殘疾人和慢性病患者的生活經歷而被賦予進壹步特殊性(即關懷)的親密接觸形式1。

這是壹種黑人殘障親屬關系,它認識到黑人生活在被期待承受所謂“沒有未來”命運的方式;我們當前的世界對健全人經驗的特權排除了獲得空間、關系和支持的方式,從而進壹步加劇了對黑人生命的“註定死亡”假設,而不是完全重新定位它(正如它通常對非黑人殘障人士所做的那樣)

但我們知道這壹點。正是在我們日常生活背景中的關懷安全中——這種關懷不依賴於可被理解的勞動——這種親屬關系的空間,無論是實體空間、虛擬空間,還是其他形式的空間,都能夠被培養和維系。即使有時這種與其他黑人殘障身心的共融感是短暫的,它也擴展了我們當前空間和時間的界限,涵蓋了多個世界,並且希望能夠為未來的可能性模式開辟新的道路。

在這裏,無障礙的需求(和願望)不再是壹種遷就,而是被理解為壹種必要性;殘疾不再被隱蔽化,也不再是為了響應白人至上主義的要求,毫無疑問地為自己命名,並提交壹份精心記錄的診斷和病情檔案作為所謂的證據;與彼此的關系不再伴隨著要求去迎合能力主義的舒適,而是以集體的努力來保護並提供我們的身心,使其在那個時刻正是它們所需要的樣子。

對於我們中的許多人來說,像 Careworn & Coil 作品所提供的這樣的空間是少之又少的,它為我們提供了壹個浮標,讓我們在這裏與那些同樣經歷過、並且在世界中以相似方式被定位的人壹起, 獲得休息和避難。它們是邀請我們以優雅的姿態命名並接納我們的脆弱,分享我們身體所知的、以及它們如何獲得這些知識的常常是難以捉摸的本質,釋放對不僅僅是行動或生產力的期望,更是釋放在壹個由不僅是能力主義,甚至是反黑人體面政治構建的世界中,表現“健康” (或更真實地說, “還好”)的情感勞動作為生存形式的期望。

在這裏,觀看的行為是壹種重新定位我們經驗的方式——這些黑人殘障生活的各個方面,我們明知它們的存在,卻不斷被要求否認或忽視——從私人化轉向公共化。這種挑釁性的觀看方式極大地扭曲了時間,將時間縮短為我們經驗的更全面的多棱鏡式表達,因為我們的經驗經常被我們的身體思維重塑和改造,仿佛在瞬間經歷了多重時刻。

這是壹種認可的行為,反對我們當今世界那種暴力的欲望,不僅否定我們個人和集體的經驗,還試圖在結構上和精神上否認我們之間的相互依存。它有力地提醒我們,表明我們能夠以各種方式、通過壹切手段在這種凝視與被凝視的行為中找到維系生命的親情。正如我們的黑色殘障祖先所做的,正如我們所做的,正如我們的未來必須做到的:我們共同存在,超越幸存;超越孤立。

術語表:

Crip — 這個詞被殘障社區重新提取並加以使用,可以作為名詞、形容詞或動詞來指代殘障人士;另見“殘障理論”(crip theory)。

Bodymind— 這個術語用於殘障研究和女性主義研究中,描述身體和心智是相互依存的,不能分開看待的觀點。

Spoons/Spoony — “勺子理論”(Spoon theory)是壹種隱喻,用來描述壹個人可用於日常活動和任務的身體或精神能量的數量,以及這種能量是如何變得有限的。

這個術語由美國作家Christine Miserandino在2003年發表的壹篇文章中創造。

藝術家簡介:

Christina Oyawale (2000 年出生於多倫多,在多倫多和溫尼伯生活和工作)自稱是 「無政府主義朋克少年」,同時也是新興的多重身份藝術家、平面設計師、研究員和策展人。Christina以電影、攝影和文本為媒介,透過記憶、共享的黑人女性主義歷史和知識交流創作作品,強調學習的好奇心和記錄慢節奏生活的必要性。目前,Christina正在嘗試突破新自由主義社會下對身份政治的常規利用和期待,這種體系要求被邊緣化的人以自身的身份作為代價,以換取在藝術界和學術界的 “能見度”。

Christina的作品和研究試圖促進圍繞資本主義、反黑人種族主義、對酷兒/跨性別者的歧視以及能力歧視的的公共對話。Christina認為,這些社會政治條件是我們應該共同努力去打破的。目前的研究興趣和思考集中於以下領域:社會再生產理論、Angela Davis、Naomi Klein和Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò的作品、蘇聯的酷兒歷史以及黑人女性主義的殘障理論。

Sarah-Tai Black(他們/他們)是壹位藝術工作者、策展人和評論家,出生並(大部分時間)成長於條約13區/多倫多,他們的作品旨在聚焦黑色、酷兒、跨性別和殘障未來及自由事業。他們的策展工作曾在以下地點展出:劍橋藝術畫廊(劍橋,安大略省)、鄧洛普藝術畫廊(裏賈納,薩斯喀徹溫省)、多倫多當代藝術館(MOCA,安大略省)、PAVED藝術(薩斯卡通,薩斯喀徹溫省)和A Space畫廊(多倫多,安大略省)。他們還曾在多倫多大學藝術博物館、麥克馬斯特藝術博物館等公共藝術空間工作,並擔任過PAVED藝術的臨時藝術總監。

1請參閱Mia Mingus的“Access Intimacy: The Missing Link”,該文章發布在作者的博客“Leaving Evidence”上

Translation by Christina Yao

The New Gallery & Christina Oyawale gratefully acknowledge

the support from the following organizations:

the support from the following organizations: