all my little failures

Andrew McPhail

March, 2008

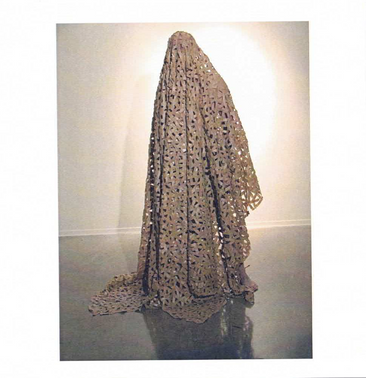

Andrew Mcphail’s performance sculpture all my little failures is a testament to the powerful effects of bodily knowledge against the backdrop of homogenous ‘information’ that is so much a part of our culture.

The 5000 band-aids required to make the piece function together as tightly as a symphony, with each individual player blending into the overall sound as they are deftly maneuvered by the model/conductor’s body throughout crowds of viewers. The modest beige colour of the veil and the library-quiet rippling noises emitted during its movements betrays the grandiose, obsessive labour required to join each tiny vinyl piece to the other, and the booming nature of the subject matter. Each band-aid is a reminder that recalls the body, its first-hand experience of collapse and our longing to avoid it.

We recognize these familiar everyday disasters. We know about hiv/aids already. Its mark is everywhere - overflowing from baskets of safer sex materials and health class curricula, in ‘awareness raising’ ad campaigns for products with charitably directed proceeds, in the bodies of our dear friends. It shouts to us in capital letters from public service announcements. Despite picturing it and understanding what it means. With the pretense of keeping us comfortable, popular media has picked up where we left off in this representational crisis, making sure that we know what the virus ‘looks like’, because “to see it is, at some level, to conquer it - to hold it at bay.”1 This mass visibility occurs in two contradictory but complacent fashions - through microscopic and macroscopic lenses. In the microscopic arena, fluid organic matter is broken down into colour-coded geometric forms that engage in epic, diametrically opposed battles with devastating and decisive outcomes. On the other hand, the sea of humanity implicated in the hiv/aids pandemic is macroscopic, seething out of their homes in droves, gradually filling up continents.

The scale of Mcphail’s all my little failures is rather jarring in this respect. There is only one man in one garment. It is a self-portrait, highy personal but void of the most revealing clinical details. Where is the sea of activists, the giant video projection, and the packed lecture hall with still images that we have come to expect? Where is the institution-like ‘immune system’, here are the computer-animated veins teeming with blimp-like red blood cells? Essentially, where is the anonymity of the viewer, or the ease of being able to dismiss something because it has been dealt with via automatic, knee-jerk reactions that ultimately pay lip service to the real issues at stake?2 In his modest performance, McPhail provides us with a seamless transition from pandemic to endemic. Referring to the progressive nature of local initiatives in his essay Criticism as Activism, David Miller notes that “What sort of [hiv/aids] crisis you find yourself in depends ... on who constructs the narrative around the imaginary turning point, what sort of narrative is constructed, and why such a construction is formed at such a time in such a place”.3 In other words, the crisis can be read as a properly impossible Crisis, or as a starting point for the radical re-negotiation of cultural symbolism.

Typically, audiences view work about hiv/aids from a ‘safe’ distance, and are able to differentiate the art from themselves, in a process that mimics serodiscordant relationships. The art is seropositive, we are seronegative.

The 5000 band-aids required to make the piece function together as tightly as a symphony, with each individual player blending into the overall sound as they are deftly maneuvered by the model/conductor’s body throughout crowds of viewers. The modest beige colour of the veil and the library-quiet rippling noises emitted during its movements betrays the grandiose, obsessive labour required to join each tiny vinyl piece to the other, and the booming nature of the subject matter. Each band-aid is a reminder that recalls the body, its first-hand experience of collapse and our longing to avoid it.

We recognize these familiar everyday disasters. We know about hiv/aids already. Its mark is everywhere - overflowing from baskets of safer sex materials and health class curricula, in ‘awareness raising’ ad campaigns for products with charitably directed proceeds, in the bodies of our dear friends. It shouts to us in capital letters from public service announcements. Despite picturing it and understanding what it means. With the pretense of keeping us comfortable, popular media has picked up where we left off in this representational crisis, making sure that we know what the virus ‘looks like’, because “to see it is, at some level, to conquer it - to hold it at bay.”1 This mass visibility occurs in two contradictory but complacent fashions - through microscopic and macroscopic lenses. In the microscopic arena, fluid organic matter is broken down into colour-coded geometric forms that engage in epic, diametrically opposed battles with devastating and decisive outcomes. On the other hand, the sea of humanity implicated in the hiv/aids pandemic is macroscopic, seething out of their homes in droves, gradually filling up continents.

The scale of Mcphail’s all my little failures is rather jarring in this respect. There is only one man in one garment. It is a self-portrait, highy personal but void of the most revealing clinical details. Where is the sea of activists, the giant video projection, and the packed lecture hall with still images that we have come to expect? Where is the institution-like ‘immune system’, here are the computer-animated veins teeming with blimp-like red blood cells? Essentially, where is the anonymity of the viewer, or the ease of being able to dismiss something because it has been dealt with via automatic, knee-jerk reactions that ultimately pay lip service to the real issues at stake?2 In his modest performance, McPhail provides us with a seamless transition from pandemic to endemic. Referring to the progressive nature of local initiatives in his essay Criticism as Activism, David Miller notes that “What sort of [hiv/aids] crisis you find yourself in depends ... on who constructs the narrative around the imaginary turning point, what sort of narrative is constructed, and why such a construction is formed at such a time in such a place”.3 In other words, the crisis can be read as a properly impossible Crisis, or as a starting point for the radical re-negotiation of cultural symbolism.

Typically, audiences view work about hiv/aids from a ‘safe’ distance, and are able to differentiate the art from themselves, in a process that mimics serodiscordant relationships. The art is seropositive, we are seronegative.

This is not so the case with all my little failures. The human scale and the overtly sensual band-aid material of McPhail’s garment combine to implicate YOUR sympathy. Beneath the veil lies an area for contemplation, a place free of moralizing judgements and the oppressive urge to blindly react, where the link between “the contemplative and active life” that makes some politicized art so effective4 can be realized.

The form of the veil is charged, and filled with mixed associations- the generous swathes of bandages increase into a series of elegant fluted wrinkles at the bottom, suggesting a burqa, or perhaps more immediately in the Western world, the virgin Mary. McPhail is careful to avoid limiting “drag” stereotypes that are too often used to support a homophobic approach to describing hiv/aids5, though - the strictly utilitarian material and the determined yet uneventful passage of the model suggest the profound ordinariness of day to day living far more than superficial sickness.

The model weaves through crowds, simultaneously exposed and camouflaged - but are the band-aids keeping illness inside, or out? Each tiny hole in the garment functions as a metaphor or actual entry point for one of more than a thousand possible ailments, the Trojan Horses of our paranoid minds. The terrifying invisible resides in each new bruise, mole, and ache that passes through us, rendering us into continually beleaguered, tragic figures of self-defeat. Thankfully, McPhal proposes an end to this caricature. Under the veil, our psychosomatic education about hiv/aids begins, and the liminal gap between infection and disease is prolonged and articulated. For McPhail, this space has proven to be very fruitful in respect to both personal discovery and public artmaking.

Our fantasies of all-powerful scientific solutions and our clinical dismissals of the visceral are refuted in the intimate, one-body basis of Andrew McPhail’s work. More importantly, all my little failures re-ignites the issues that we would rather convince ourselves through empty gestures or over-politeness. It serves as a disturbing reminder of what we have come to expect from art related to hiv/aids three decades since the outbreak - impersonal educational sermons, abstracted information, or relevant, pro-active experience?

-Wednesday Lupypciw

Sources

1 Petra Kuppers. “Medical Museums and Art Display: The Discourses of AIDS”, The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performances and Contemporary Art. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2007. p.157.

2 James Miller. “Criticism as Activism”, Fluid Exchanges:Artists and Critics in the AIDS Crisis, ed. James Miller. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992. p.204.

3 Miller p.197

4 Miller p.204

5 Kuppers, p.157-158

Wednesday Lupypciw is a Calgary-based artist and arts programmer. She has worked for the United Nations Association of Canada doing research into artistic expression surrounding HIV/AIDS.