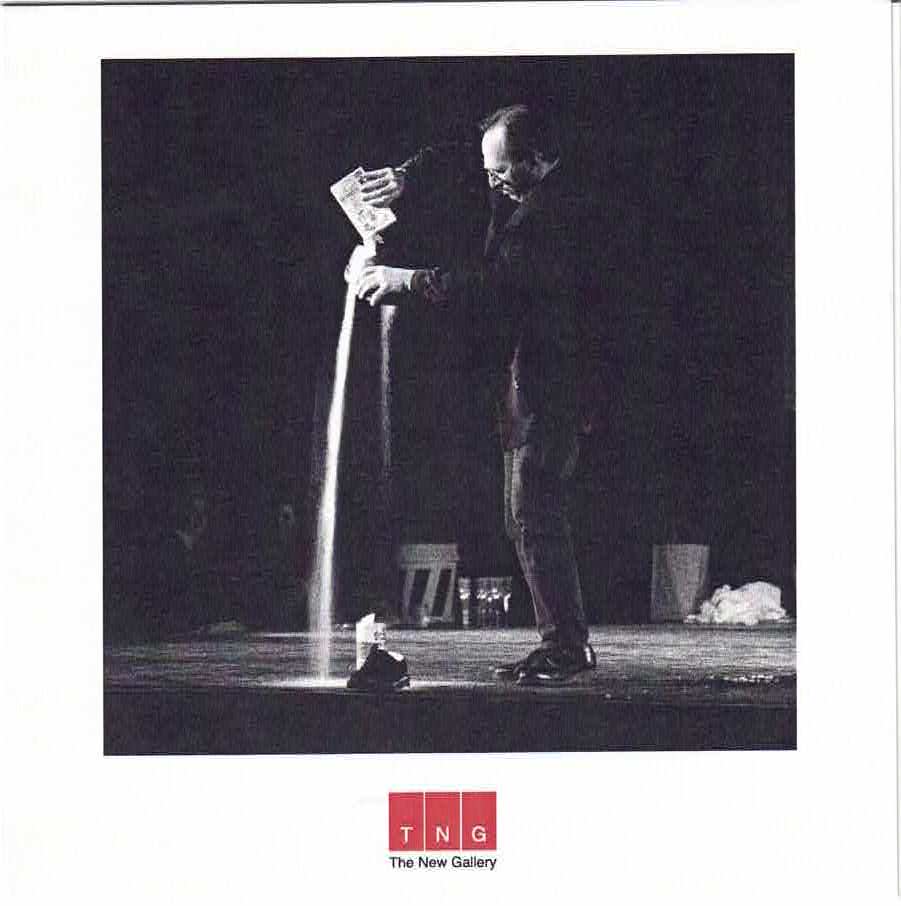

Time

Ken Friedman

January 20 - February 17, 2007

In August of 1966, Dick Higgins sent me to meet George Maciunas for the first time. George peppered me with questions. What did I do? What did I think? What was I planning? I was planning to become a Unitarian minister. I did all sorts of things, things without names, things that jumped over the boundaries between ideas and actions, between the manufacture of objects and books, between philosophy and literature. George listened for a while and then he invited me to join Fluxus. I said yes. A short while later, George asked me what kind of artist I was. I was startled: until that moment, I had never thought of myself as an artist. George thought about this and said, ‘You’re a concept artist’.

This was before the visible explosion of conceptual art, and what George meant by concept art is what we now call intermedia, adopting a term that Dick adapted from an earlier and different usage of Samuel Coleridge Taylor. The event score is a natural expression of the intermediate idea. My first engagement with scores took place in 1966 when George and Dick brought me into Fluxus. When I described my ideas and projects, George immediately planned a series of Fluxus editions based on my ideas.

At the time I met Dick and George, I did not call my projects art. I had no name for them. Despite the fact that I had no name for my activities, I enacted them in public, systematic, and organized ways, realizing them in public spaces, parks and visible arenas as well as in churches and conference centers, radio programs, and once or twice, on television, I saw these activities as a form of philosophical or spiritual practice.

The fact that my activities did not take place in the context of art made me quite different to the other Fluxus people. George Brecht, Nam June Paik, George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Yoko Ono, Mieko Shiomi, and others worked with event scores before I did. These were important artists and composers while my activities have no name. These artists and composers worked in New York, Tokyo, London, and other metropolitan art scenes while I was a youngster, first in New London, Connecticut, and then in San Diego, California. Their work was known internationally, albeit underground, while I had no contact with the art world, creating my nameless projects and realizing them in any environment that seemed possible. At the same time, this fact meant that these projects were my own. The ideas were original to me and because I was not active in art or music, the others did not influence me.

At George Maciunas’s suggestion, I began to notate my activities in the form of event scores. These scores recorded activities for the repertoire of projects I had generated since childhood. The first public piece I recall doing, and one of the first that I described to George, involved scrubbing a public monument on the first day of spring in 1956. This became my first event score. The distinction between realizing a public action and notating it in the form of a score is the distinction that governs my work before 1966. An artist once said that if my first score pieces took place in 1956, I would have been more important than George Brecht. This is exactly the different between George Brecht and me, and it is the reason that I make no such claim. Brecht scored his ideas in the 1950s. He was a central figure in pre-Fluxus activities and early Fluxus. I created my first scores when I entered Fluxus.

While I developed a repertoire of activities, repeating them often in the years between 1956 and 1966, these only became formal scores in 1966 when George Maciunas explained the tradition of scores. I communicated ‘how to do it’ instructions to friends in letters and bulletins, and I made comments in my own notes and diaries, but I understood and conceived these as scores when George encouraged me to notate my ideas for publication by Fluxus.

Context determines the nature and status of social activity and I only entered the art context in 1966. While I performed my actions or realized the projects notated in ym event scores as early as 1956, these were not art works. For the past forty years, I have worked with events.

Dick Higgins long ago suggested that I find a better way to make a living than by making art: he said it would buy me the freedom to make the art I want. That is what I did. Some days I am an artist, and some days not, but I’m always active in the liminal space of intermedia. I enter that space with events.

- Ken Friedman, 2006

Artist’s Biography:

Ken Friedman is an artist and designer who had his first solo exhibition in New York in 1966. For over 40 years, he has been active in the international experimental laboratory for art, design, and architecture known as Fluxus. He worked closely for many years with Fluxus co-founders George Maciunas and Dick Higgins. He collaborated extensively with Milan Knizak and he conducted the world premiere of Nam June Paik’s First Symphony in 1975.

Friedman’s work is found in museums and galleries around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Tate Gallery, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, and the Hood Museum of Art. The University of Iowa Alternative Traditions in the Contemporary Arts now owns Friedman’s research papers and archive. At the turn of the millenium, The University of Iowa Museum of Art mounted an extensive exhibition of Friedman’s work. The exhibition is accessible in a permanent web catalogue at URL http://sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu/atca/subjugated/five_front.htm

At the beginning of his career, Dick Higgins suggested to the then-young Ken Friedman that he develop skills outside the art world that would make him independent of the art market and free him to pursue the radically experimental work for which he is known. He did so, becoming an editor, designer, publisher, and consultant before starting a career as a scholar in leadership, knowledge management, culture studies, and design. Today, he is Professor of Leadership and Strategic Design at the Norwegian School of Management in Oslo, and at Denmark’s Design School in Copenhagen. He also serves as an editor of several leading journals, including Design Studies, The International Journal of Design, and The Journal of Design Research.

Friedman lives with theologian Ditte Friedman and their dog Jacob in an island village on the west side of the Oslo Fjord. Copenhagen is a long day’s sail straight south from the next island over.