MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

Carrie Allison – An Identity Metaphor, 2017, beads on pine with reflective surface.

These Threads Hold Memory

Carrie Allison

July 6–August 10, 2019

Exhibition Description /

These Threads Hold Memory brings together works of art that decenter western notions of information and data by Indigenizing western information paradigms. This exhibition utilizes beading as a tool to share statistics, thoughts, and contemplate stereotypical and perhaps unknown narratives. By mixing what is known as “technology” such as websites, QR codes, and video with beadwork, this exhibition asks the viewer to recenter and value Indigenous histories and ways of knowing. Carrie Allison uses beading in her practice to connect to ancestors, to gain insight with Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies. Beading is ceremony, a meditative practice that centers oneself in the present, a repetitive gesture that asks the maker to consider the content of the object being made. Beading is, and always has been, a tool for engaging Indigenous ways of knowing and being. It’s not about the individual bead; it’s about the collective, the whole. Through labour intensive methodological processes, this exhibition situates Indigenous language, visual culture, and knowledge as legitimate technologies.

Exhibition Text /

These Threads Hold Memory features beaded works by Carrie Allison that explore knowledge and knowledge mobilization. Misinformation about Indigenous communities and technology has been internalized as truth within Canadian understanding. Allison joins the ranks of artists such as Barry Ace and Skawennati, whose art practices use electronics and the Internet to carve out space for Indigenous voices as well as affirm that Indigenous peoples have always been technologically inclined. Like many other aspects of Indigenizing, first we must unlearn colonial narratives around contact.

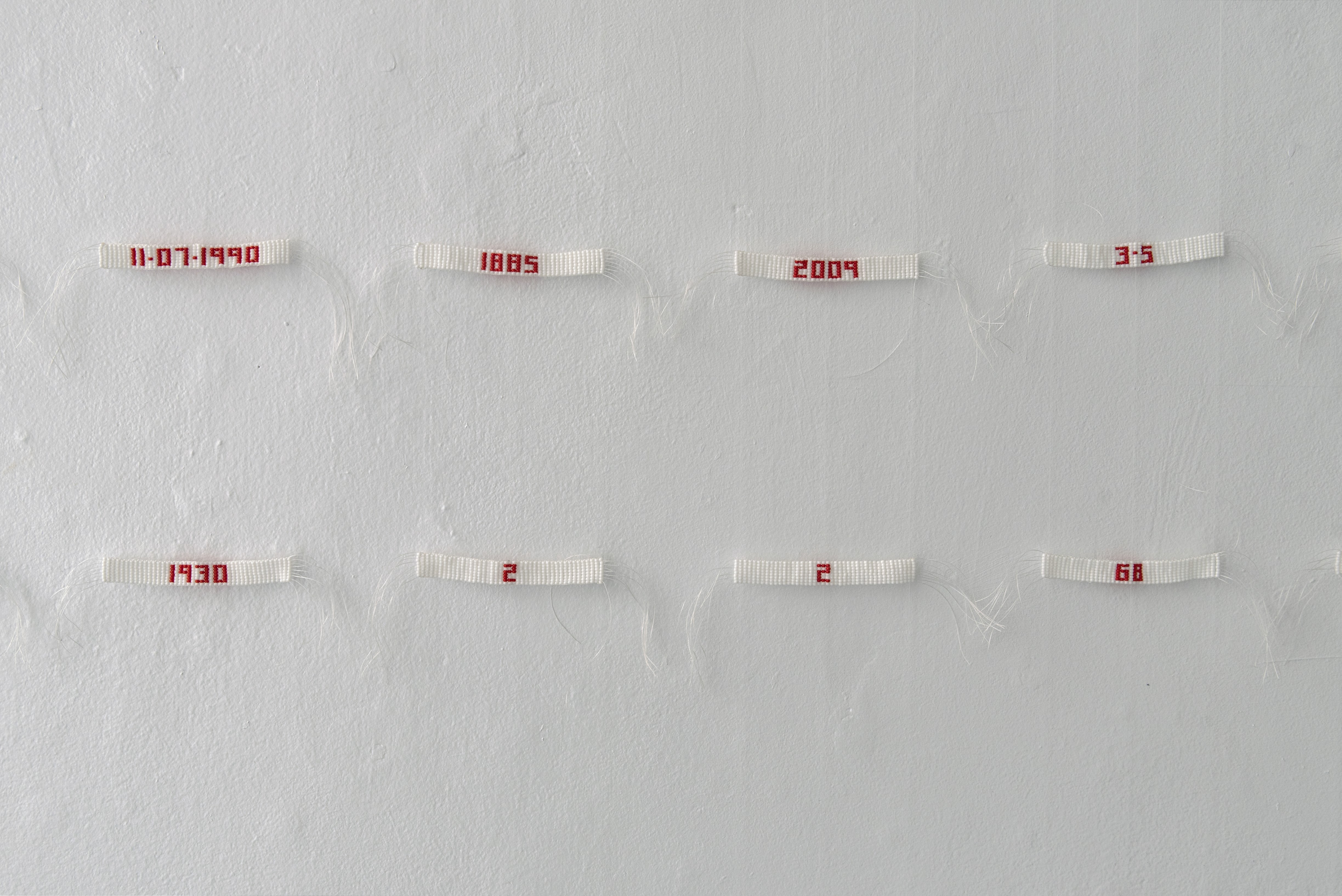

150 is a series of loom-beaded objects that play with the appeal of interactive technology; scanning codes, clicking numbers, and finding information on the Internet. This style of research relates to the process of beading and storytelling, and brings those elements to a gallery space. Beading, when done in groups, revolves around jokes, cackles and the sharing of information or ideas on relevant topics. Beading, like all artwork, isn’t done in a vacuum and 150 presents those layers of (underappreciated) knowledge in a medium that is recognized and holds cultural value; via electronics.[1]

Allison, like many Indigenous folks (myself included), have to work for cultural knowledge which continues to be suppressed through genocidal acts sanctioned by nation-state strategies; as a result, knowledge isn’t something that can be commodified and it’s through the generosity of our community that we can receive these gifts. Identity Metaphor and Kiskisohcikew document the process of learning Cree through repetition, as well as the struggle for access, with these language lessons being delivered over the phone.

The Western-European relationship to knowledge is defined by the “enlightenment” period,[2] that everyone has a right to “know” the answer and that emotional investment in the subject reduces the ability to be impartial. This is compounded by the fact that gendered relationships expect womxn and underrepresented communities to share knowledge with no reciprocation and that they don’t know how to properly utilize it. An example of this was the art movement Primitivism;[3] This also justified residential schools, anthropologists entering communities to take people’s belongings, and the settler resistance to prioritizing oral histories.

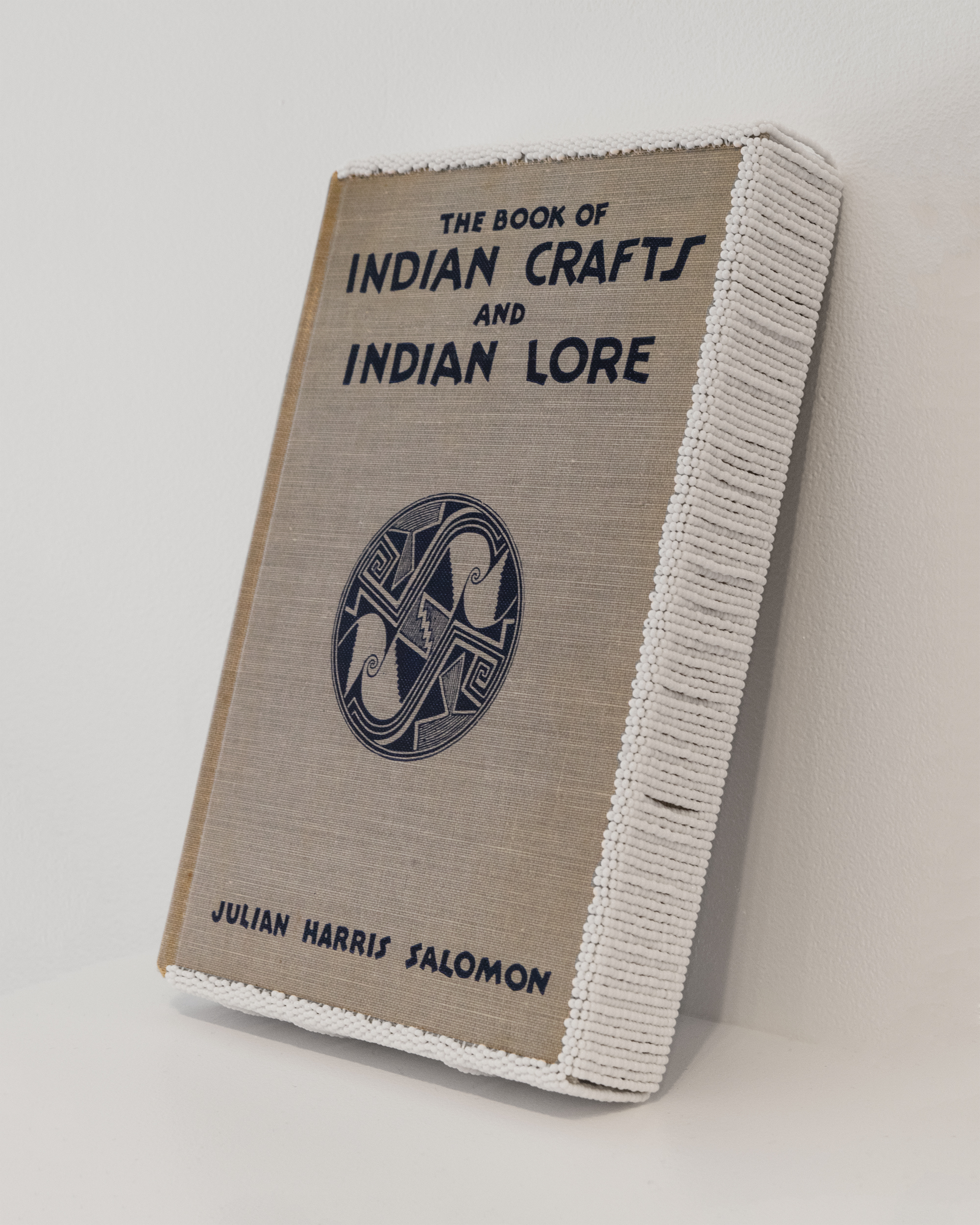

Recently, there has been recognition that Indigenous communities have always had technology and important knowledge. Articles have circulated where cells of trees are the same as the art of the local community, sage is medicinal, Indigenous peoples have been in North America and the sites could be located via oral histories [FH22], and so on. In Allison’s work, Book Intervention: Library of misrepresentation and False Narratives they subvert the adage that published information is truth. Through redacting terms by blocking them out with black beads,the figures in the story are re-centred, in this case the depiction of a Western cowboy is covered with Allison’s intervention of a beaded bison.. Using beads as the tool to reframe, and even bind the books shut, Allison is emphasizing the ongoing challenge Indigenous knowledge systems pose to foundations of western-European thought.

The work within These Threads Hold Memory explores a conceptual trifecta; the relationships between storytelling and electronics; the validity of both Indigenous epistemologies and western-European thought; and the relationship between Indigenous technology and western-European thought. This essay isn’t to say that western-European knowledge systems don’t have value, it’s that they aren’t without their flaws. Once structures are willing to examine their shortcomings and acknowledge Indigenous epistemologies and systems as equal, everyone will benefit.

–Franchesca Hebert-Spence, BFA MA

Further Reading:

Nicholas, George. “When Scientists “Discover” What Indigenous People Have Known For Centuries.” Smithsonian.com. February 21, 2018. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-science-takes-so-long-catch-up-traditional-knowledge-180968216/.

Wang, Jenica. “Primitivism: A Study of Cultural Appropriation.” Omeka RSS. Accessed June 5, 2019. http://omeka.wustl.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/primitivism.

–

[1] I use the word electronics instead of technology because the assumption that electronics are synonymous with technology invalidates forms of technology or knowledges that are materials other than electronics.

[2] The Enlightenment period occurred during the 18th century and is the foundation of all Western-european scientific processes. It affects how humanities and otherwise conduct research and was compounded by colonialism.

[3] Primitivism was an art movement where artists used imagery from various colonized cultures to depart from representational imagery. Artists from the communities whose aesthetics were appropriated were not welcomed into the art community.

Biographies

Carrie Allison is an Indigenous (Cree/Métis, European descent) visual artist, writer, arts administrator and educator, born and raised on unceded and unsurrendered Coast Salish Territory (Vancouver, BC). Situated in K’jipuktuk since 2010, Allison’s practice responds to her maternal Cree and Métis ancestry, thinking through intergenerational cultural loss and acts of resilience, resistance, and activism, while also thinking through notions of allyship, kinship and visiting. Allison’s practice is rooted in research and pedagogical discourses. Her work seeks to reclaim, remember, recreate, and celebrate her ancestry through visual discourses. Allison holds a Master’s in Fine Art, a Bachelor’s in Fine Art, and a Bachelor’s in Art History from NSCAD University.

Franchesca Hebert-Spence’s first engagements with art were as a maker, creating an empathetic lens within her curatorial praxis. Her grandmother Marion Ida Spence was from Sagkeeng First Nation, on Lake Winnipeg, Manitoba. Kinship and its responsibilities direct the engagement she maintains within her community and, by facilitating a plurality of voices, complicates oversimplified narratives. The foundation of this practice stems from Ishkabatens Waasa Gaa Inaabateg, Brandon University Visual and Aboriginal Arts program. She is an Adjunct Curator, Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Alberta and Independent curator.

Territorial Acknowledgments

TNG gratefully acknowledges its home on the traditional territories of the people of the Treaty 7 region, including the Blackfoot Confederacy (Kainai, Piikani and Siksika), Métis Nation of Alberta Region III, Stoney Nakoda First Nation (Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley), and Tsuu T’ina First Nation. TNG would also like to acknowledge the many other First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have crossed this land for generations.