MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

Image: ONE’S PARENTS ARE GIVEN THE LONE INSTRUCTION TO EACH TAKE A PHOTOGRAPH OF A POINSETTIA THAT ONE HAS GIVEN TO ONE’S DYING GRANDMOTHER; THE RESULTANT IMAGES ARE PLACED IN FRAMES BUILT BY ONE’S GRANDFATHER TO ONE’S SPECIFICATIONS by Benjamin Bellas.

Image: ONE’S PARENTS ARE GIVEN THE LONE INSTRUCTION TO EACH TAKE A PHOTOGRAPH OF A POINSETTIA THAT ONE HAS GIVEN TO ONE’S DYING GRANDMOTHER; THE RESULTANT IMAGES ARE PLACED IN FRAMES BUILT BY ONE’S GRANDFATHER TO ONE’S SPECIFICATIONS by Benjamin Bellas.Soft Movements in the Same Direction

Steven Beckly & Benjamin Bellas

April 11 to May 17, 2014

This exhibition pairs the work of two artists concerned with representations of intimacy, impermanence, and distance. With video, photography, and found objects, they provide forms for the inarticulable ache of an unknown absence.

When a member of The International Brotherhood of Magicians (IBM) dies, their conjuror’s wand is ceremoniously broken in half at the grave. In Broken Wand Service for Deceased Members, the ritual’s official manual written by magician and IBM chaplain Rev. Canon William V. Rauscher, loved ones are urged to look forward to seeing the deceased again “in fellowship where no trickery abounds.” [1]

Often, during this ceremony, a fake wand is used. The classic, easily recognizable black and white conjuror’s wand is recommended, and has often been saw-cut along the shaft in advance to ensure a smooth and expert split. [2]

It’s like how my boyfriend brought all of my stuff with him when he broke up with me.

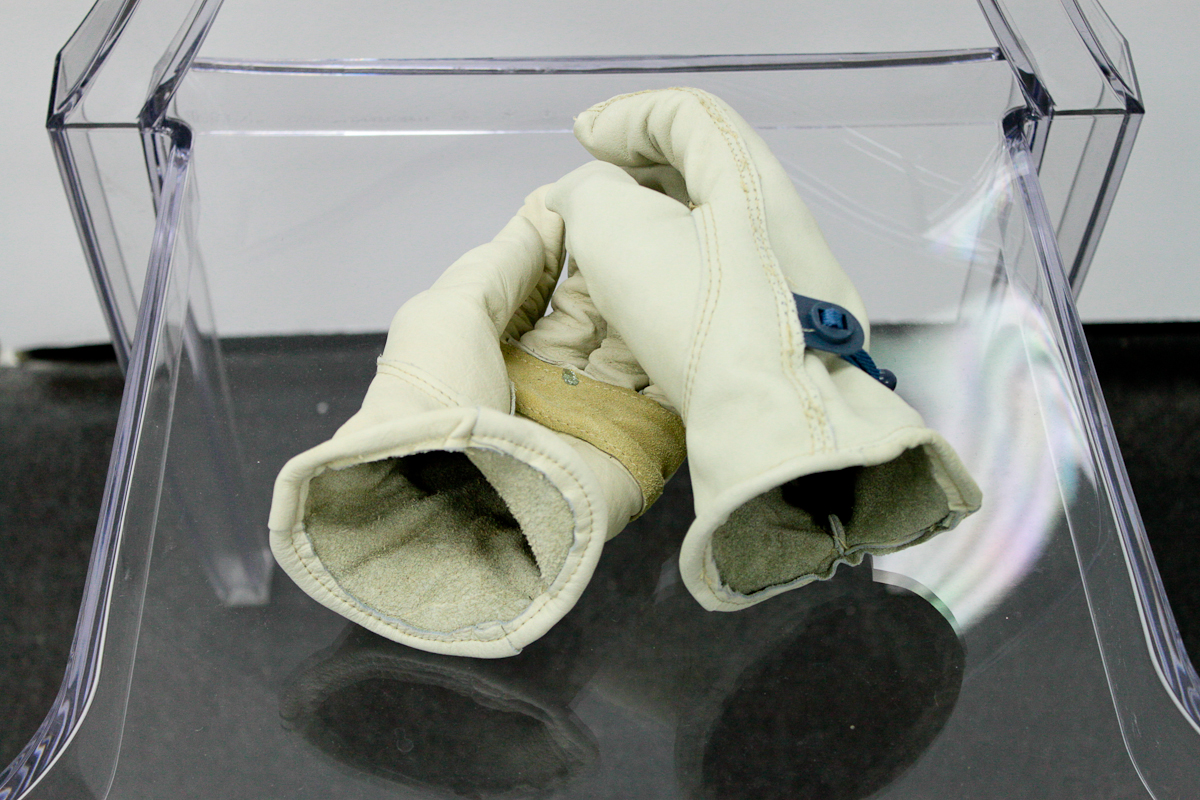

Objects are similes; they are the word “like.” They construct a likeness or countenance; they will a presence that is absent. But even in this description, the object takes the actual person or relationship represented away from you and replaces it with only itself. The wand was like the magician’s life, the powder pink sweater returned to me like the touches of my own hands.

Critic, poet, and professor Stephen Burt writes, “We have ‘like,’ as we have poetry, because we do not ever wholly possess or understand the object of our love.” [3] Art, then, is our theurgical attempt at conjuring the countenance of our love. In some ways though, the very essence of the presence of an object is the marked absence of who or what you are thinking of. Like psychoanalyst D.W. Winniscott’s understanding of the “transitional object,” art can attempt to replace whatever relationship or person we have been robbed of, as a child’s cherished blanket—or in my case, Julie the uncomfortably firm doll—replaces a friend. [4]

In her essay “In Plato’s Cave,” Susan Sontag writes, “As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure.” [5] Photos and objects inhabit this space of what is real and unreal, alive and not alive; they, like a simile, are a container with which to catch the infinity of experience. They are only capable of capturing a portion of what was, of securing it and quantifying it, and in turn securing and quantifying a portion of the maker. The breaking of the wand summed up the indescribable conundrum of eternal separation with one motion, describing it accurately but only in one way of a million.

Along comparable lines of compartmentalized thinking, philosopher, psychologist, and physician William James said in a lecture on mind-curists and the religion of healthy-mindedness, “The ideal, so far from being co-extensive with the whole actual, is a mere extract from the actual, marked by its deliverance from all contact with this diseased, inferior, and excrementitious stuff.” [6] It is the belief in something behind, above, and better than reality. This can be art.

Then later, when describing those with a more uneasy view, whose happiness exists infected with contradiction, James says this:

The pride of life and glory of the world will shrivel. It is after all but the standing quarrel of hot youth and hoary eld. Old age has the last word: the purely naturalistic look at life, however enthusiastically it may begin, is sure to end in sadness.

This sadness lies at the heart of every merely positivistic, agnostic, or naturalistic scheme of philosophy. Let sanguine healthy-mindedness do its best with its strange power of living in the moment and ignoring and forgetting, still the evil background is really there to be thought of, and the skull will grin in at the banquet. [7]

This can be art too, one way of a million.

It’s interesting that the breaking of the conjuror’s wand, a gesture so seemingly genuine, so intent on indicating the nakedness, the truth of death and loss, is a trick itself. It’s the last trick. It was sawed in advance. Built to snap. Maybe my suspicion concerning this pure act is the same suspicion I had when I started looking at Julie as just a doll. Like one of James’ negativists, I believe there is trickery above and behind; art is a manipulation of the viewer’s feelings. At the same time and in equal measure, I remember what it’s like to see someone escape from a straightjacket; I remember what it was like when you crawled into bed with me in the middle of the night. And even if I try to describe its happening, already defeated by the incompetency of an object or a word, I believe it. Sincerity or faux-sincerity, who’s to say?

– Lindsay Sorell

Works cited

[1] Allen, Jonathan. “Where No Trickery Abounds.” Cabinet Spring No. 49. 2013: 102-103.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Burt, Stephen. “Like.” The American Poetry Review January/February 2014: 17–21. Print.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave.” On Photography. London: Allen Lane, 1978. Print.

[6] James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience, Oxford: Oxford Press, 2012. Print.

[7] Ibid.

Biographies

Steven Beckly is a Toronto-based interdisciplinary artist. Working with photography, publications, sculpture, and installation, his practice explores the complexities of relationships, intimacy, closeness, and sexuality. His work has been shown nationally and internationally, including exhibitions at Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography (Toronto), Art Metropole (Toronto), Art Souterrain (Montréal), the Photographic Resource Center (Boston, MA), Photo Center NW (Seattle, WA), Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (Philadelphia, PA), and the Center for Book and Paper Arts at Columbia College (Chicago, IL).

Benjamin Bellas stages subtle interventions and gestures within the everyday in an attempt to understand the experience of understanding; cognition itself. Bellas has exhibited his work nationally and internationally at various venues such as Contemporary Istanbul; Track 16, Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; la Space, Hong Kong; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago; and Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki. He is the recipient of a Franklin Furnace Award and an Illinois Art Council International Artist Grant, and has been awarded residencies at Redux Contemporary Art Center, 1a space, and the Contemporary Artists Center. His writing has been published in journals such as Cadillac Cicatrix and Drain Magazine. He holds a BA in Studio Arts with minors in Art History and Philosophy from the University of Pittsburgh and received his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Bellas is formerly a member of the faculty in the Contemporary Practices Department of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is currently Assistant Professor of Art at Washington College.

Lindsay Sorell graduated from the Alberta College of Art + Design’s Drawing program in 2012. She recently curated and edited the online publication FORTUNE COOKIES: Articles on the future of art, participated as an artist-in-residence with The New Gallery in collaboration with the Calgary Society of Animated Objects, held BEDTalks, a series of guest lectures in her bedroom, participated in the projection show/YouTube party everyday at The Art Gallery of Calgary, and currently lectures on the history of cheese at Janice Beaton Fine Cheese, Calgary.

We produced a 33-page catalogue in conjunction with this exhibition. Available in our online store or as a free PDF.

This exhibition was made possible in part by funding from the Ontario Arts Council and the Toronto Arts Council.