MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

Pulling Back the Paper

Curated by Su Ying Strang with essential contributions by Curatorial

Assistant Steph Weber and Translator Christina Dongqi Yao

September 25 — October 23, 2021

Exhibition Description /

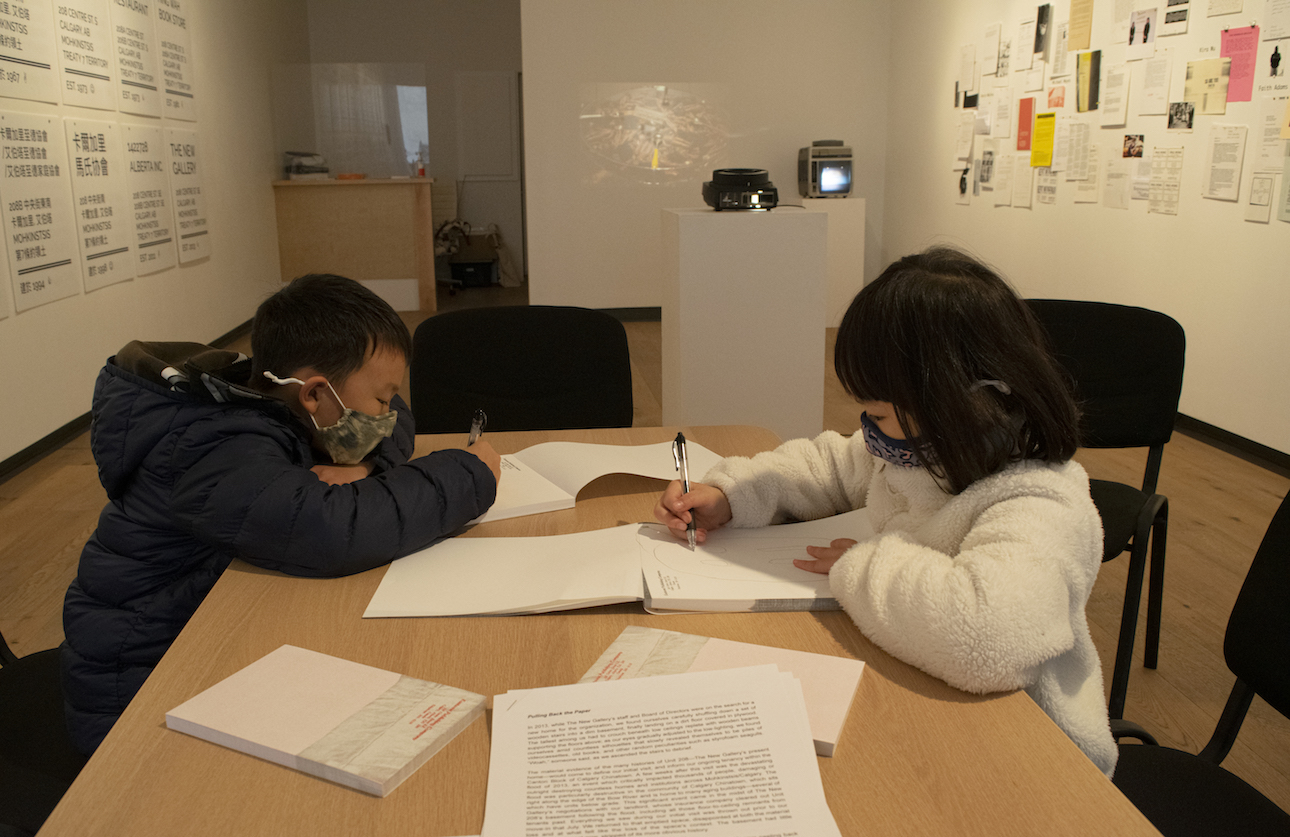

Pulling Back the Paper is an archival exhibition and research lab that gathers and shares the expansive histories of two intersecting communities from The New Gallery’s past and present— the Calgary faction of the Minquon Panchayat and Calgary Chinatown. This interactive project invites community members to help build out the organization’s archival materials related to these histories, addressing gaps found within the “official” institutional record.

Curatorial Text /

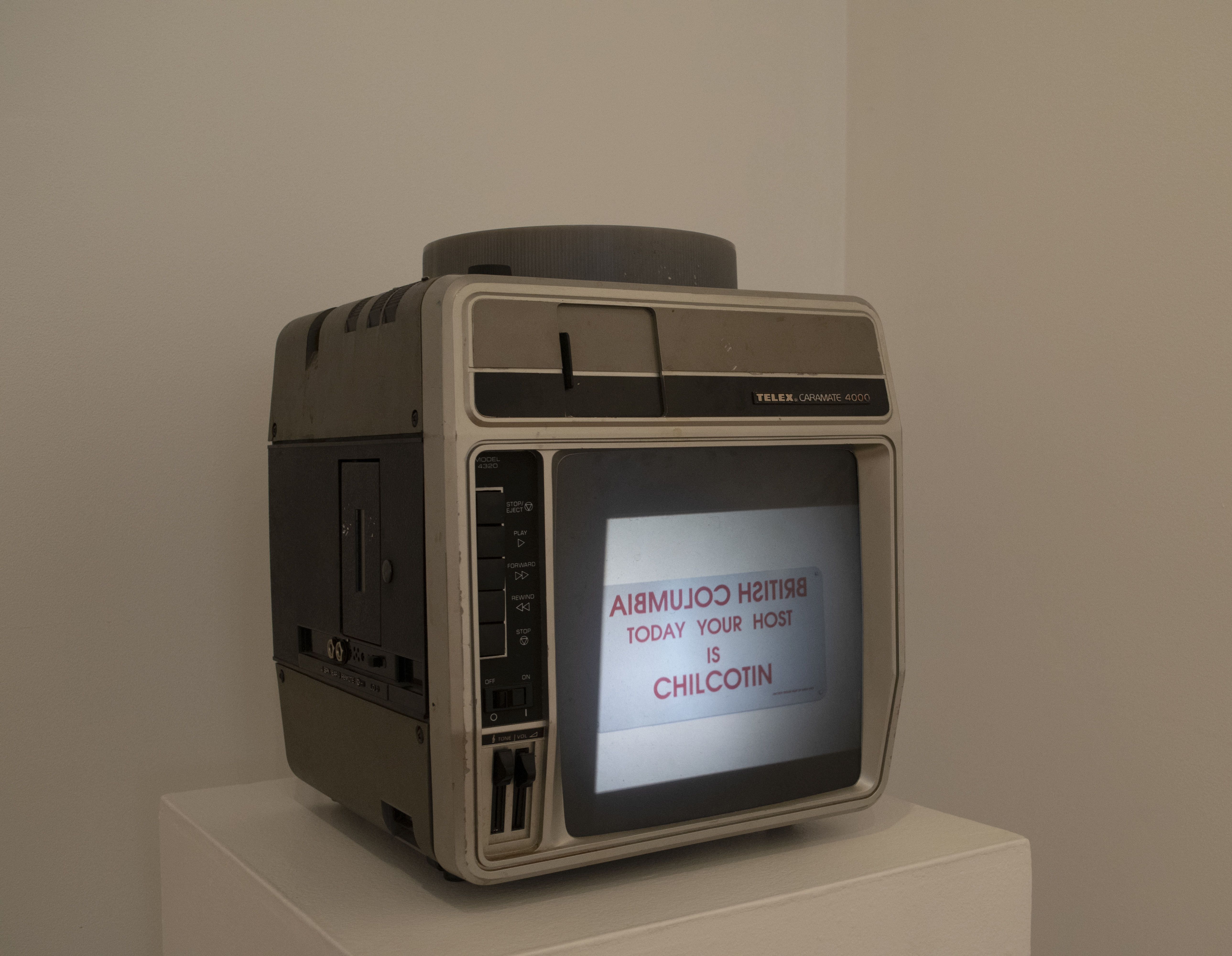

In 2013, while The New Gallery’s staff and Board of Directors were on the search for a new home for the organization, we found ourselves carefully shuffling down a set of wooden stairs into a dim basement, finally landing on a dirt floor covered in plywood. The tallest among us had to crouch beneath low ceilings replete with wooden beams supporting the floors above; as our eyes gradually adjusted to the low-lighting, we found ourselves amid countless silhouettes that slowly revealed themselves to be piles of videocassettes, old books, and other random peculiarities such as styrofoam seagulls. “Woah,” someone said, as we ascended the stairs to debrief.

The material evidence of the many histories of Unit 208—The New Gallery’s present home—would come to define our initial visit, and inform our ongoing tenancy within the Canton Block of Calgary Chinatown. A few weeks after this visit was the devastating flood of 2013, an event which critically impacted thousands of people, damaging or outright destroying countless homes and institutions across Mohkinstsis/Calgary. The flood was particularly destructive in the community of Calgary Chinatown, which sits right along the edge of the Bow River and is home to many aging buildings—several of which have units below grade. This significant event came in the midst of The New Gallery’s negotiations with our landlord, whose insurance company cleared out Unit 208’s basement following the flood, including all those floor-to-ceiling remnants from tenants past. Everything we saw during our initial visit was thrown out prior to our move-in that July. We returned to that emptied space, disappointed at both the material loss and at what felt like the loss of the space’s context. The basement had little immediate interest now, stripped of its more obvious history.

Some time after—days, weeks, or months—some old layers of wallpaper peeling back from one of the wooden support beams downstairs caught my eye. Tucked behind this worn membrane was a small sheet of cut stationery: on one side, a drawing proclaiming, “Dad the GREAT!” alongside a portrait of Dad, and on the other, the letterhead for “Eastwest Publishing Company,” sharing our address, “208 Centre Street S.E.” The drawing, later identified as belonging to the Wong family, offered a glimpse into one of the stories and lives that this space has held. I carefully placed the drawing back in its home, considering it a good omen to have with us, gently informing the work at The New Gallery upstairs.

The move to Calgary Chinatown changed The New Gallery, and it also changed me. Upon being steeped in this neighborhood, with its deep connections to Chinese culture and community, I began to unpack my own identity and relationship to being a mixed-race Chinese American settler. While my mother, of Chinese descent by way of Malaysia, did her best to connect my siblings and I with our traditions and culture, the forces of assimilation that permeated the mostly white suburbs we grew up in dampened many of her efforts; instead I succumbed to the homogenizing effects of my surrounding community. Any strong desire for a connection to my own cultural background remained dormant until I found myself spending most of my days firmly couched in a large community of other Chinese folks through my work at The New Gallery within Calgary Chinatown. Despite not having any family lineage in this particular place, I found a warm, open community that has helped me connect to, and build a better understanding of, my own cultural heritage and family.

I would revisit the found drawing several times throughout my tenure at The New Gallery. Each time, that fragment of stationery offered a moment of joy and curiosity about the previous identities of this space and the people within. This small artifact would be the point of departure for Pulling Back the Paper, with my curiosity shifting into a responsibility to know more about and acknowledge those who had come before and contributed to Calgary Chinatown while inhabiting this space. The histories of Units 208 and 208B 1 are conjured through the creation of a timeline of past organizations that have been listed as tenants of these units from 1911 to present day. Records also cite lodgers at “208 Centre St.” sporadically between 1911 and 1955. This documentation provides some additional insight, including the types of organizations, census data for individuals, and the occasional headline of “newsworthy” events. However, these resources flatten the community’s narratives to what fits within these limited information-collecting frameworks and often privilege a singular voice, leaving little space to account for the expansive histories that have occurred. It struck me that the vibrancy of the community I had gotten to know over the past several years—the richness evident in the found drawing—was missing from these historical records.

This growth and learning occurred alongside my ongoing work to understand and reckon with the settler-colonial dynamics implicit in working in Calgary Chinatown, which is located on Treaty 7 Territory. This land holds the living cultures and histories of the Blackfoot Confederacy (Kainai, Piikani and Siksika First Nations), the Stoney Nakoda (Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nations), the Tsuu T’ina First Nation, and the Métis Nation of Alberta Region III—among countless other contributions from First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have travelled through and gathered on this land. When learning about and acknowledging the histories of Calgary Chinatown, one must also ask, what historical and contemporary intersections exist between this community and the Indigenous peoples of this region?

In 2019, we invited artist Annie Wong to take part in the Calgary Chinatown Artist Residency. One of her resulting projects, Braids in the Front / Braids in the Back speaks to early Chinese settler and Indigenous community-building, and was conceptualized after Wong met Blackfoot Elder Sheldon First Rider through the residency. That first meeting was in Unit 208B, our Resource Centre, where so much of The New Gallery’s history is kept; this is where Elder Sheldon shared many of his stories and teachings, and where a new relationship with Wong led to the creation of this artwork. The connection between Indigenous and Chinese communities demonstrated through this artwork not only reveals an important history—it also points to a necessary future of collaboration and coalition building.

It wasn’t until after working in Calgary Chinatown for a few years that I recognized I could exhale—a much-needed relief resulting from being connected to and constantly within a large racialized community. It was this breath that motivated me to want a better understanding of the histories and labour of racialized folks in the communities I am part of. I was curious not only about the people who had made their lives in Calgary Chinatown before me, but also about the contributors to artist-run culture, in particular that of The New Gallery. An opaque sentence in our official history2 mentions that The New Gallery had worked with a group called the Minquon Panchayat, which I later learned translated to Rainbow Council.3 I rooted around in The New Gallery’s archives, wanting to know more about this group, but I found that our documentation surrounding the Minquon Panchayat was inconsistent and scattered, with no clear narrative outlining their integral contributions specific to The New Gallery. An essay by Tomas Jonsson in Silver: 25 Years of Artist-run Culture spoke about this relationship in a little more detail, as did Clive Robertson’s Policy Matters: Administrations of Art and Culture. While grateful for these references, I couldn’t help but wonder where the accounts were from those who were directly involved in this partnership between The New Gallery and the Minquon Panchayat.

The Minquon Panchayat was a coalition of racialized artists that formed in 1992 at the Association of National Non-Profit Artists Centres (ANNPAC) / Regroupement D’Artistes Des Centres Alternatifs (RACA) Annual General Meeting and conference in Moncton, NB. Artist and activist Lillian Allen was invited to give a keynote address that year, during which she made the call to action for ANNPAC/RACA to grow its membership to include 40% racialized members in response to the Annual General Meeting’s “dismally low presence of First Nations and peoples of Colour participants.”4 Allen’s leadership moved the conversation about racial equity in artist-run centres leaps and bounds forward, resulting in the immediate formation of the Minquon Panchayat. Over the course of the next year, the Minquon Panchayat worked ardently toward creating a path to racial equity in artist-run centres—the first of a two-year commitment from ANNPAC/RACA—which culminated in the 1993 artist-run gathering, It’s a Cultural Thing organized by Cheryl L’Hirondelle5, and ANNPAC/RACA’s ensuing Annual General Meeting.6

This national movement, and the then-forthcoming 1993 gathering, spurred the creation of a local faction of the Minquon Panchayat in Mohkinstsis/Calgary, which connected racialized artists across the local community. Members from this local faction were invited to select artists for the 1994-95 programming year at The New Gallery. Several members, including Faith Adams, Steve Nunoda, Kevin Walkes, and Kira Wu, served on that year’s Programming Committee, while others, including Ashok Mathur, Darmody Mumford, Steve Nunoda7, and Aruna Srivastava served on The New Gallery’s Board of Directors. Michael Mayes, another member of the 1994 Programming Committee, was not directly involved with the Minquon Panchayat, but shared their goals of racial equity, as evidenced through his programming selections.8

As I learned about this history of the Minquon Panchayat and Units 208 and 208B, parallels began to take shape. I started to notice how often the lives and labour of racialized communities are difficult to access in archives or are undocumented altogether. The New Gallery’s artist files include correspondence that is occasionally signed by or addressed to specific members of the 1994 Programming Committee—this happened primarily during the initial invitation to programmed artists. In a few cases, Programming Committee members are referred to as exhibition facilitators or as the curators of their programming selections, and files contain curatorial statements or mention the committee member within the press release. However, the Minquon Panchayat and the specific context of that year’s Programming Committee are rarely mentioned, with the exceptions of: a letter from Kira Wu describing the make-up of the committee to one of her programmed artists, a letter from Henry Tsang citing “the new and improved Programming Committee agenda,” and a final piece of correspondence from Thomas Heyd addressed to Steve Nunoda of the “Panchayat Programming Committee.” Lastly, a newsletter from Latitude 53, several copies of which were tucked into the artist file for Survivals: Cultures & Contexts,9 has a column contributed by the Calgary faction of the Minquon Panchayat. The column outlined the collective’s purpose, encouraged new members to join, and promoted their collective’s upcoming exhibition, DOORS, at TRUCK Gallery.10 Archived city directories and the City of Calgary’s records of Units 208 and 208B—like The New Gallery’s archival records of the Minquon Panchayat—imperfectly recall the history of these units in the Canton Block. Tenants and owners of Units 208 and 208B are listed inconsistently, occasionally misspelled, the dates of many of their tenures unclear, and the units themselves appear under many guises—sometimes labelled 206 and occasionally including a Unit A or a Unit C.

Returning to Annie Wong’s Braids in the Front / Braids in the Back, an important history is elicited: first shared orally with the artists-in-residence by Elder Sheldon First Rider, the kinship between local Indigenous communities and early Chinese settlers is indicated through the phrases cited in the work’s title, which shares the monikers that these communities used to refer to one another.11 The obscurity of this history is another example of how settler-colonialism, in tandem with white supremacy, has actively suppressed the histories and contributions of countless communities—a violence that continues today. The narratives that have surfaced while developing Pulling Back the Paper begin to illustrate the numerous voices that get left out of institutional records, and the processes of how they are excluded. How can we insert multiple perspectives and communities in the narratives shaping our histories? The unacknowledged labour and direct accounts from racialized peoples—in this particular case, the intersecting communities of Calgary Chinatown and the Calgary faction of the Minquon Panchayat within the context of Treaty 7 Territory—is at the centre of this archival exhibition and research lab.

The obfuscation of these distinct yet intersecting histories—whether intended or not—amounts to the erasure of the significant contributions and happenings led by racialized people and their movements. This exhibition, in response, problematizes the official archive and record by exposing its deficiencies, biases, and its violent erasures. Our communities’ histories must not privilege a single author, and instead, must make space for simultaneous truths and perspectives to be captured. In that spirit, Pulling Back the Paper is intentionally a research lab, and I invite community members to add to and annotate these parallel histories with their truths. Please share your additions, amendments, and related perspectives during this project, including within this curatorial text. Throughout the exhibition run there will be a live link to a Google Doc with editing and commenting capabilities. I welcome respectful additions to this text, which will be added to The New Gallery’s archive of this event.12 Collaborative in spirit, this project aims to rebuild our histories collectively, and to know and share all that makes up our pasts—even that which sometimes resides behind a layer of wallpaper but none-the-less persists now and into the future.

This project would not have been possible without the time, support, and knowledge of so many generous friends and colleagues. My deepest thanks to Lillian Allen, Natasha Chaykowski, Lynne Fernie, Sheldon First Rider, Tomas Jonsson, Alice Lam, Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Ashok Mathur, Michael Mayes, Victoria McInnis, Nate McLeod, Evan Neilsen, Cassandra Paul, Aruna Srivastava, Zool Suleman, Sandra Vida, Kevin Walkes, Steph Weber, Annie Wong, Paul Wong, Kira Wu, Christina Dongqi Yao, and Yolkless Press (Areum Kim & Teresa Tam). I’d also like to express my gratitude to the community of Calgary Chinatown, the Minquon Panchayat, and the past and present contributors to The New Gallery.

—Su Ying Strang

Territorial Acknowledgments

TNG gratefully acknowledges its home on the traditional territories of the people of the Treaty 7 region, including the Blackfoot Confederacy (Kainai, Piikani and Siksika), Stoney Nakoda First Nation (Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley), Tsuu T’ina First Nation, and Métis Nation of Alberta Region III. TNG would also like to acknowledge the many other First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have crossed this land for generations.

Footnotes

- In 2018 The New Gallery moved the Resource Centre into Unit 208B, which is located directly above the Main Space in Unit 208.

- “In 1992 The New Gallery partnered with Minquon Panchayat, a national coalition supporting artists of colour, to raise awareness around issues of race and gender, and to actively address these issues in the context of regular The New Gallery programming.” For the full text, visit: http://www.thenewgallery.org/about/history/

- The program guide for It’s A Cultural Thing explains that “Minquon” is the Maliseet word for “Rainbow” and that “Panchayat” is Hindi for “Council.” p. 9

- For additional information about the formation of the Minquon Panchayat and the objectives of the movement, see Lillian Allen’s ”Transforming the Cultural Fortress: Imagining Cultural Equity,” Parallélogramme, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 54

- Cheryl L’Hirondelle was the Minquon Panchayat’s Animation Coordinator who organized the celebrated landmark event, It’s a Cultural Thing, which took place in the Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre. Cheryl also served on The New Gallery’s Board of Directors in 1993, and was the Programming Coordinator at TRUCK from 1991-93.

- The 1993 ANNPAC/RACA AGM was an attempt to achieve Lillian Allen’s call to action to reach 40% racialized membership—the result of a year of planning and labour by the Minquon Panchayat. New racialized representatives showed up and were ready to join the organization, but when it came time to vote, they were presented with several barriers to joining by existing members. This break in trust by ANNPAC/RACA members resulted in the Minquon Panchayat walking out of the AGM, and the initiative crumbling. Several existing ANNPAC/RACA members resigned in solidarity with the Minquon Panchayat, leading to the eventual dissolution of ANNPAC/RACA. For more information about this significant event in artist-run history, read the 1993 issue of Parallélogramme vol. 19, no. 3., “Anti-Racism in the Arts.”

- Steve Nunoda is listed on p. 97 in the Silver catalogue as a Board Member as well as a member of the Programming Committee in 1994.

- Individual names are listed on p. 97 of the Silver catalogue, but are not cited as members of the Minquon Panchayat. Membership to the Minquon Panchayat was confirmed through personal interviews with Kevin Walkes, Kira Wu, Ashok Mathur, Michael Mayes, Aruna Srivastava in August 2021.

- The newsletter was likely included in this artist file as it had information about a Latitude 53 exhibition by Teresa Marshall, one of the artists included in the Survivals: Cultures & Contexts exhibition at The New Gallery. Coincidentally, this newsletter also included information about an exhibition by Kent Monkman, who was programmed at The New Gallery during the 1994-95 programming year by committee member Michael Mayes.

- TRUCK Gallery is now called TRUCK Contemporary Art.

- For a full project description and image of the work, visit: http://www.thenewgallery.org/braids-in-the-front-braids-in-the-back/

- If you’d like to be credited for your contributions, please sign in to your Google Account when editing, or comment on your additions with your name. All other contributions will be cited as “anonymous.”