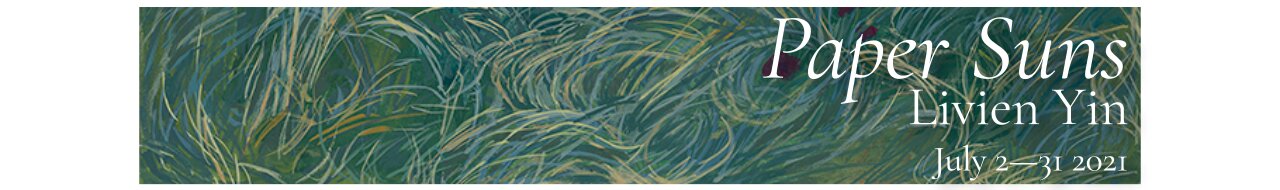

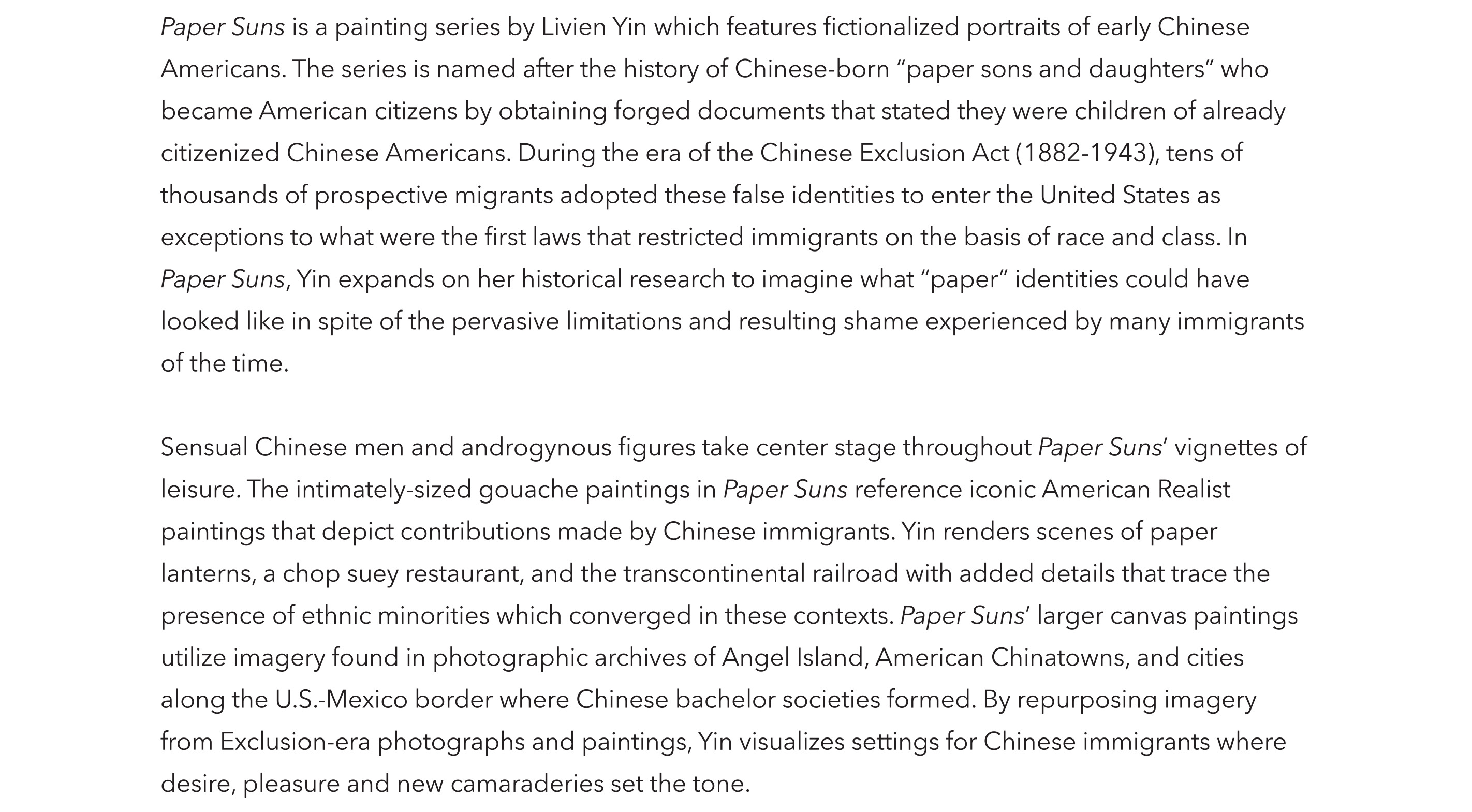

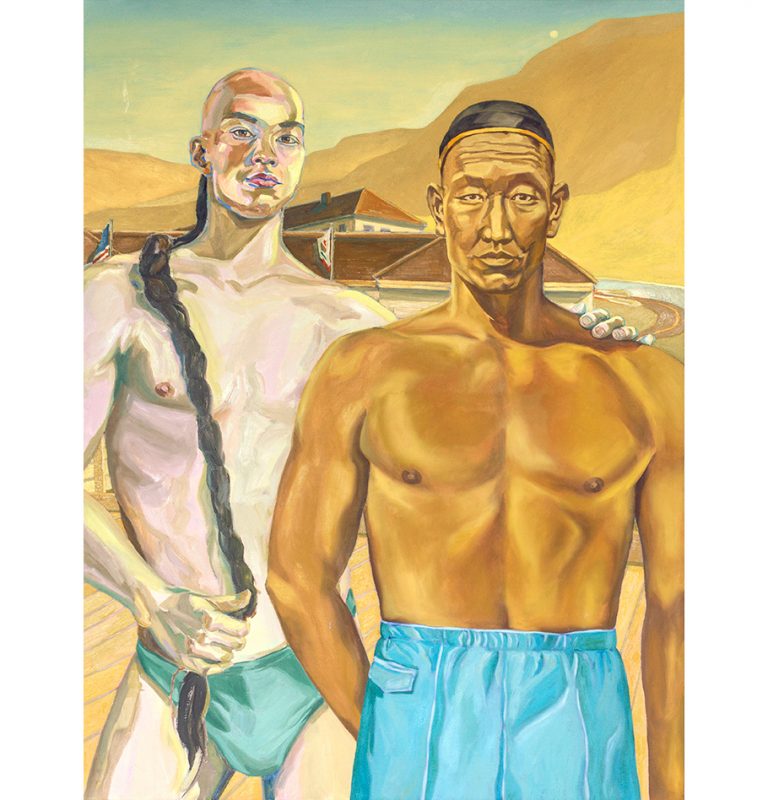

Livien Yin’s Paper Suns are like joyful ghosts animated by pleasure: their own pleasure, a viewer’s pleasure, the pleasure of the brilliant artist who has rendered them into muscular, charismatic life. Like the protagonists conjured into being by Tom of Finland — a direct visual referent for Suey, the first painting in the series — Yin’s characters are extra-vital, irrepressible with desire and agency. They flirt in bars, they lounge, they sip champagne. They linger in my mind long after I have looked away; I confess that I’m tempted to write erotic stories about them.

They haunt, delightfully so. The immolations triggered by the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco turned nearly an entire city’s immigration records into ash, simultaneously erasing its Chinese residents from the official government archive and creating a space for imagined belonging in these lacunae. Absence, then, as the very ground on which a bluff of citizenship could be ratified into some fragment of reality. In some history books, “paper sons and daughters” is the name given to those Chinese men and women, boys and girls, who immigrated to the United States through non-legal filial claims. Numerous first-person and scholarly accounts of their lives (for example, in Tung Pok Chin’s memoir Paper Son) seem to emphasize the fear that animated them and kept them silent for decades, silence that would seep from one generation to the next. As if they were crafty in a melancholic and stifled sort of way, with joy or pride secondary to fear. Without diminishing the material hardships they faced, as well as the constant threat of organized violence or deportation, I wonder what these very real sons and daughters — who existed beyond the space of the page — would tell us about their lives if we were able to ask. To which aspects of their quotidian routines would they wish to give voice? Which doors would they crack open, which would they keep closed?

Yin has presented her paper suns/sons without names, but I don’t get the sense they would readily share them with us anyway. As if they might give you one name on a Saturday night and another on a Sunday morning. These sons refuse racialized emasculation and subservience; they are the stars of

their American films and fill the frames of their portraits with assurance. They don’t ask to belong, they know they do. Suey, after all, is a restaging of Edward Hopper’s “American classic” Chop Suey (1929), which I was surprised to learn from Yin was actually set in a Chinese restaurant, though we are given few clues to discern this setting. How easily American popular memory flattens and elides details that inconvenience the narrative centrality of whiteness, but herein lies also the genius of Yin’s work, which reminds us — reminds me — that history can be resuscitated, too, and seduced back into memory.

In speaking with Yin about Paper Suns, I continually found myself circling back to Saidiya Hartman’s essay “Venus in Two Acts,” wherein she enacts a close reading of the limitations of the archives of slavery as well as a speculation of the stories whose impossibility is made immanent by the very space of the archive. Hartman writes, “[by] advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.” (Hartman: 11) Hartman’s method is, of course, inextricably tied to her subject matter, making it difficult to trace a direct line between

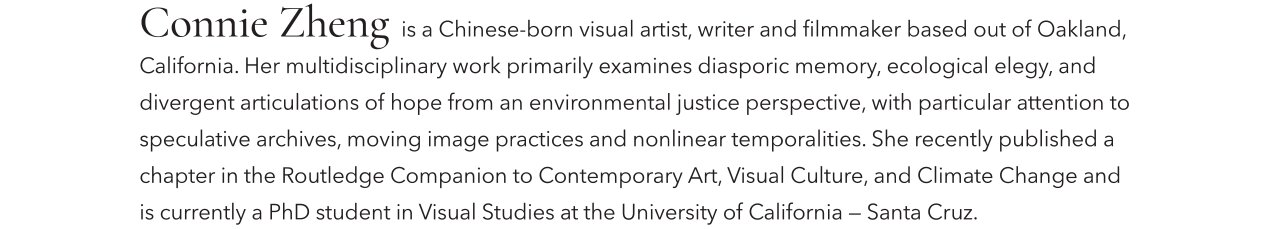

her practice of “critical fabulation” with similar practices of archive-based speculation deployed in other contexts. Yet I could not help but think of Hartman’s methodology of “critical fabulation” when encountering Yin’s work, as she potently infuses the archive with not just visual exuberance and critical imagination, but also a tender sort of attention that I would venture to call love. Yin’s paintings, with their sensuous blooms of color, announce their fabrication; they present themselves as fantasy, contemporary reincarnations of sons who have chosen anonymity, rather than being forced into it. These paper suns are born from the seams of history, the dusty silence within the gaps of the archive. And perhaps that is where they will return. But in their own time, and on their own terms. - Connie Zheng