MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

Other Histories

Amin Rehman

July 7 — August 5, 2017

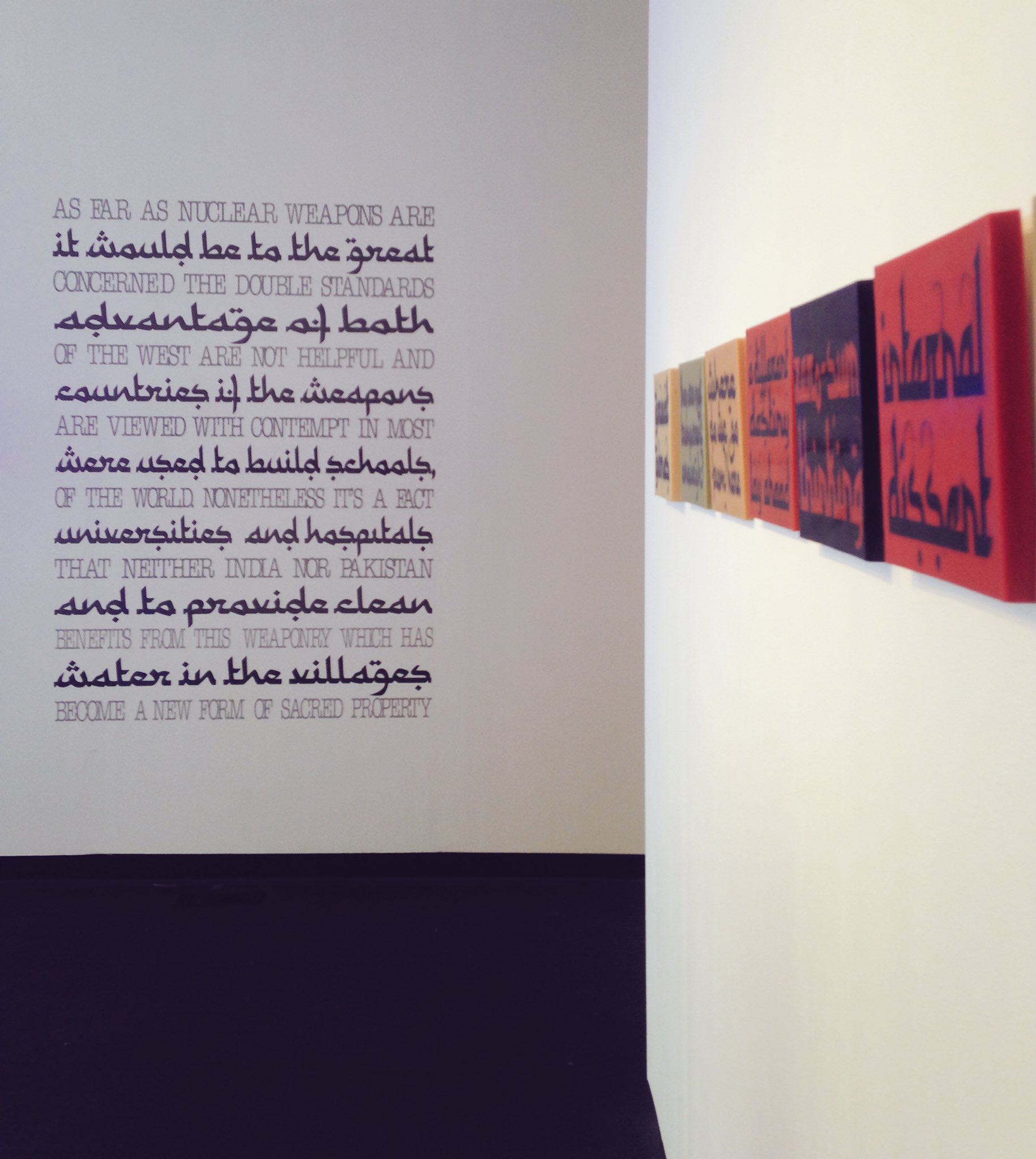

English is a Foreign Language

They make desolation and call it peace.

Agha Shahid Ali, “Farewell”, The Country With a Post Office (1997)

In the poem Farewell, Kashmiri poet Agha Shahid Ali intersperses the lines, “Your memory gets in the way of my memory / My memory keeps getting in the way of your history” throughout his verses. The lines reveal the tensions and sometimes- contradictory nature of re-telling history. In his text-based work, Pakistani-Canadian artist Amin Rehman similarly traverses the boundaries of history telling and its multiple readings. Drawing from current events, historical texts and his own personal experiences, Rehman visually weaves together words and phrases to reveal the discords of political narrative and its public reckoning.

Since moving to Canada from Pakistan in 1990, Amin Rehman has consistently delved into socio-political themes in his work. Rehman reflects, “It’s always a challenge to exhibit politically charged work. My position is one that involves negotiating but not compromising, so that, as an artist, I don’t play to the tune of hegemony.”[1] Rehman’s uncompromised and indeed provocative works push for a re-examination of both historic and contemporary texts that, despite being conveyed through simple English phrases and word pairings, question the power dynamics within situations of political unrest.

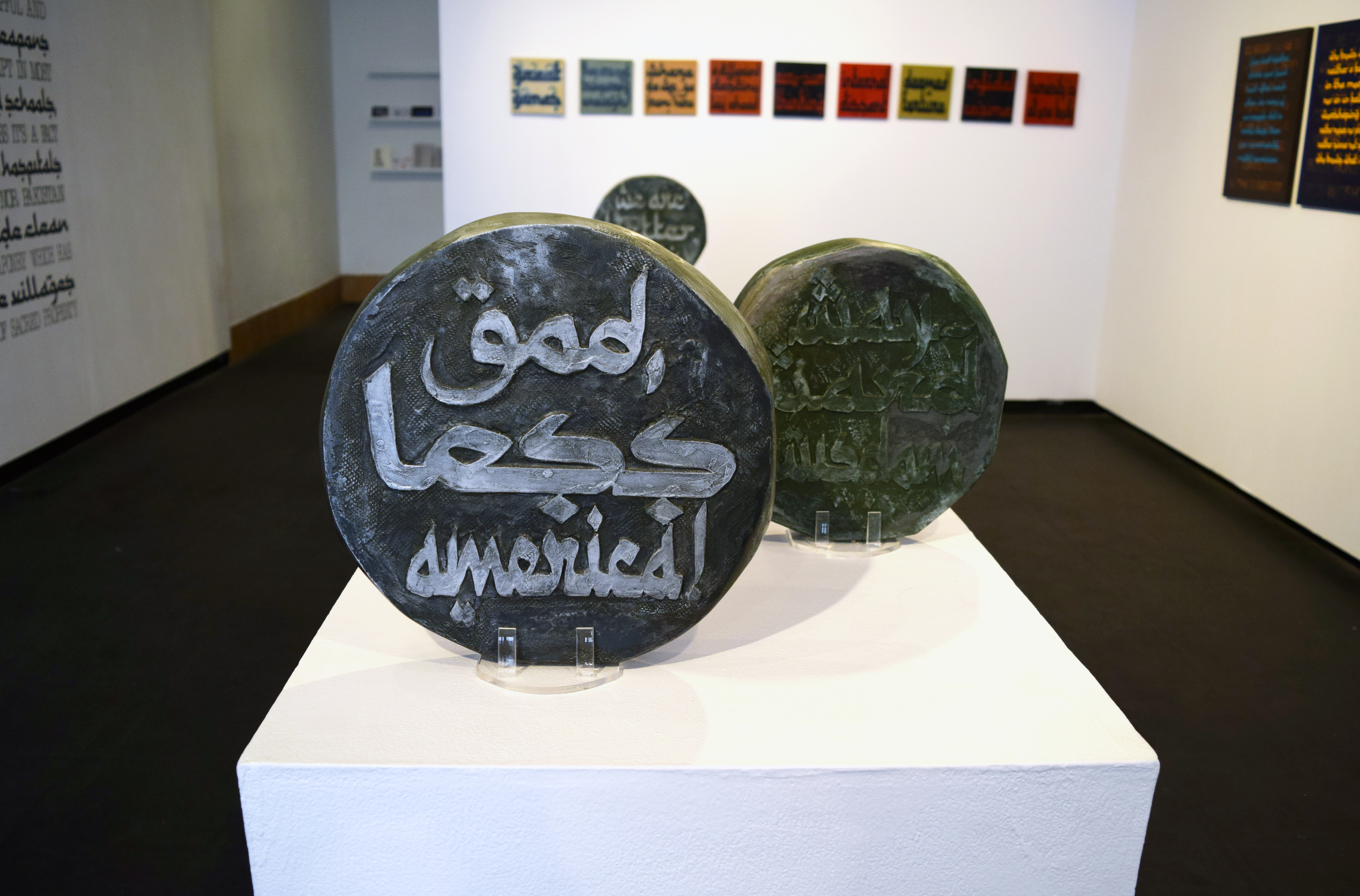

For Rehman’s integrative text-based practice not only draws on the techniques of mass communication but is also reminiscent of the installation and collage works by contemporary artists such as Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Both Holzer and Kruger transform language into art, which, in their very public presentations, help shape public discourse on topics such as labour, civil rights and identity. However, Rehman’s work makes a keen distinction in its visual renderings. In his most recent series Other Histories (2012-present), Rehman draws from the rich visual calligraphic traditions within Islamic art. Dating back to the eleventh and twelfth centuries, these commissioned manuscripts were painstakingly illuminated and written by hand. The importance and role of the written word in the Islamic tradition cannot be underestimated. As art historians Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom point out, the first revelation to the Prophet Muhammad was to “Recite in the name of thy Lord, Who taught by the pen” and that it either meant “that writing was relatively new to Arabia or that man is able to learn from writing (i.e. from reading books) what he does not otherwise know.” Moreover that “Man’s every deed is recorded in the Book of Reckoning for the final accounting on Judgment Day (Koran 69. 18-19)” also reiterates the significance of the written word.[2]

Within the Other Histories series, Rehman takes a number of different placement approaches to visualize his messages. For example, in his vinyl installations The Duel (2012) and For Globalization (2012), Rehman juxtaposes contrasting texts with contrasting fonts and colours. In The Duel, the grey arabesque text articulates the vantage point of how a duel is often fought without weapons, and on the other orange contrasting lines, “the repression striking blindly leaves people with no options…” In the work For Globalization, the texts are “For globalization to work, the empire cannot be afraid…” along with “war is just a racket…” In both works, Rehman overlays the words of British-Pakistani writer Tariq Ali with that of 1930s American Major General Smedley D Butler. By doing so, Rehman plays with the meaning and intentionality of their words. For Rehman, “the background text often speaks for the pessimistic, and foreground layer is the optimistic voice, although sometimes these are reversed.”[3]

The Duel (left) and For Globalization (right),

These works are as much about the messaging as they are about the aesthetics and font forms that are employed. As Rehman reflects, “for me, the selection of the text, process and material is very important which makes any text a successful visual. Probably, larger texts require clear selection of idea and composition, which could engage the viewer into the work.”[4] The role of lettering and arabesque script style in Rehman’s work – again, one rooted in the diverse Islamic calligraphic arts – are cultural identifiers. Written in English, the words take on a foreignness that is only ascribed to non-English languages. As writer Karl Jirgens points out, Rehman’s “Kufi-based English typography and his hybridized perspectives, all gesture to an awareness that self and ‘Other’ are actually one.”[5]

However such perspectives on hybridized languages and indeed, even cultures, has been largely viewed as being incongruous. Rather, the concept of connectedness between places and people – just as frequent in the past as in our ever-digital present – has a history beyond our current political borders and assumptions. The very fact that a Semitic language like Arabic and by extension a faith such as Islam, continues to be viewed outside the Judeo-Christian paradigm (despite shared Abrahamic roots) attests to the strength of the articulation of polarities. The late cultural theorist Edward Said, who revolutionized the ways of understanding and seeing Islam and cultures, wrote,

The general basis of Orientalist thought is an imaginative and yet drastically polarized geography dividing the world into two unequal parts, the larger, ‘different’ one called the Orient, the other also known as ‘our’ world, called the Occident or the West. Such divisions always come about when one society or culture thinks about another one, different from it; but it is interesting that even when the Orient has uniformly been considered an inferior part of the world, it has always been endowed both with greater size and with a greater potential for power (usually destructive) than the West.[6]

The play (and obfuscation) of words and meaning has in more recent history in the West gained widespread notoriety. In the age where “fake news” is used to dismiss and disavow political action and have direct and perceptible impacts on marginalized communities, Rehman’s investigation of the origins and fluidity of words and their double meanings is a poignant contestation of hegemony. The work in Other Histories asks us to read between the lines and consider alternate points of view. Here, English — a considerable colonial language —becomes a visual vehicle to show the power and dynamics of history.

-Nadia Kurd

[1] Amin Rehman in dialogue with Jamelie Hassan, email interview, 2012, p.5

[2] Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom. Islamic Arts. London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 1997, 59.

[3] Email correspondence with the Author, 2017.

[4] Jamelie Hassan, “Dialogue”, Amin Rehman: A is for… Windsor and London, ON: Artcite Inc. and McIntosh Gallery, 2013, 5.

[5] Karl Jirgens, “Medium as messenger: Amin Rehman’s typographic interventions”, Amin Rehman: A is for… Windsor and London, ON: Artcite Inc. and McIntosh Gallery, 2013, 19.

[6] Edward W. Said, Covering Islam. New York: Vintage Books, 1997, 4.

Biographies

Amin Rehman (Toronto, ON) is a multidisciplinary visual artist who has been exhibiting since the 1980s. Rehman’s interests are primarily drawn from his experience of living in Pakistan and Canada. His work engages with and comments on the current effects of neo-colonialism and globalization, encompassing multiple artistic mediums such as installation, painting, video and neon. Originally from Pakistan, he studied at the National College of Arts (Lahore, PK), the University of Punjab (Lahore, PK), the University of Manchester (UK), and the University of Windsor (ON). Rehman has exhibited extensively in exhibitions and festivals across Canada and abroad. Recent exhibitions and awards include; the Art Gallery of Regina (2014); the McIntosh Gallery at the University of Western Ontario (2012); the Art Gallery of Mississauga (2011); the Queens Museum of Art in New York (2009); with multiple Ontario Arts Council and Toronto Arts Council grants awarded between 2008 to 2013. Rehman was the recipient of Chalmers Fellowship Award in 2008, and named Artist of the Year in 2005 by the South Asian Visual Arts Collective. This fall, Rehman will be working on the Acme Artist Residency project in London, England.

Nadia Kurd is an interdisciplinary curator and art historian with a PhD from McGill University. She has special interests in arts advocacy, contemporary Islamic art and architecture as well as Indigenous visual culture from North America. In addition to working at arts organizations such as the South Asian Visual Arts Centre, Ontario Association of Art Galleries and the Prison Arts Foundation, Nadia has been the Curator of the Thunder Bay Art Gallery since 2010, where her focus is on community engagement and emerging artists in Northwestern Ontario. In recognition of her work, she was awarded the Northwestern Ontario Visionary Award in 2014 and Canadian Council of Muslim Women’s Women Who Inspire Award in 2016. She currently serves on the City of Thunder Bay’s Public Art Committee and on the board of the Historians of Islamic Art Association. In 2017, she was awarded the prestigious Hamad bin Khalifa Fellowship.