MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

It’s Gonna Rain

Divya Mehra

September 9 – October 22, 2016

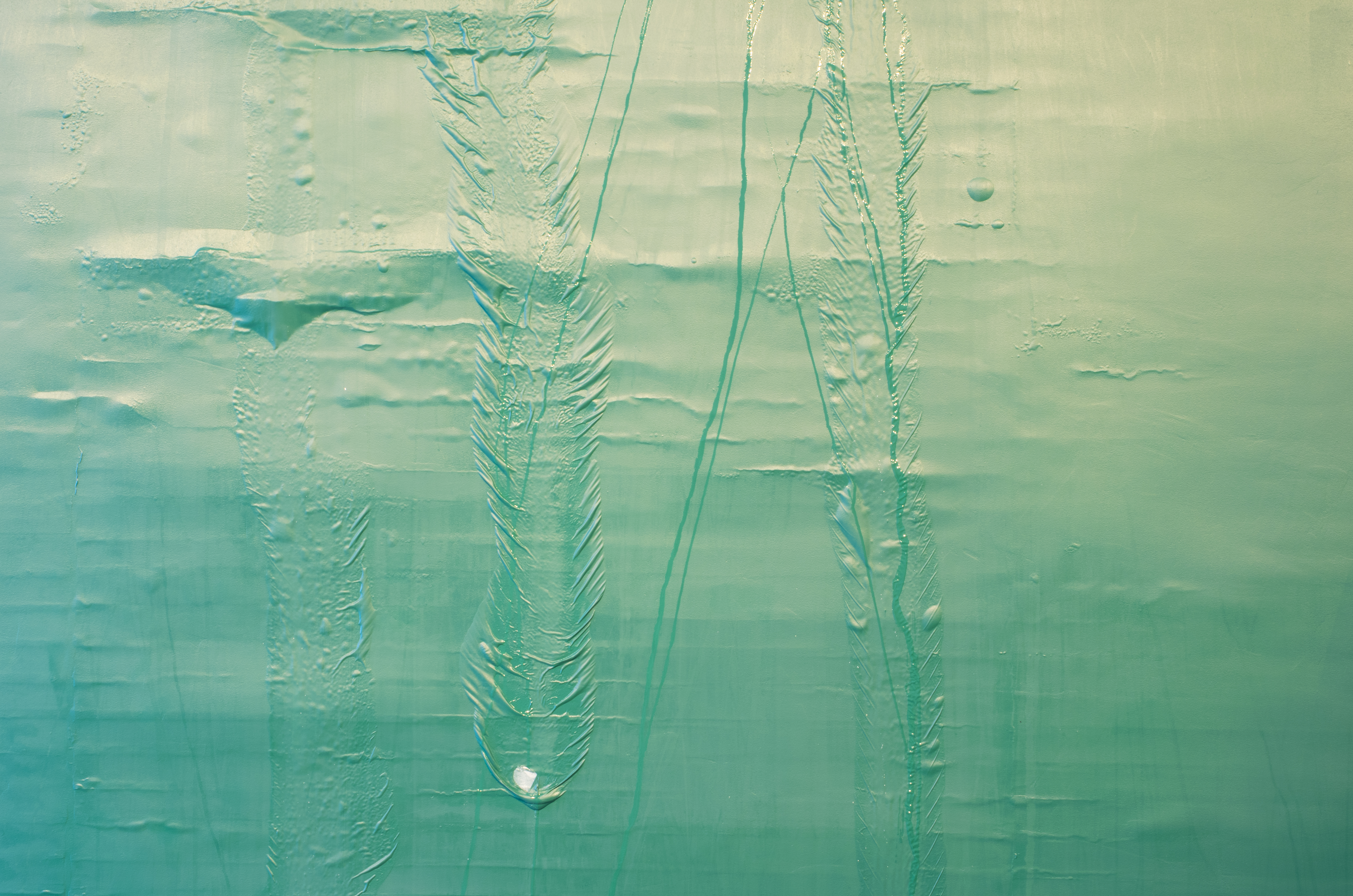

Divya Mehra. A civic death (in praise of the threat), thus coherence – of patriarchy, of ancestry, of narrative – is made by erasure and exclusion OR nothing lasts forever, I hope you will consider the sensitivities of Hindus, 2016 tree slab, 13″ x 2.5″

Image credit: Karen Asher

Essay

In Every Life

What happens when the cliché comes true? What happens when a little rain, in every life, does fall? With It’s Gonna Rain, Divya Mehra presents a trifecta of loss. This should not be mistaken for a museum of the missing; more directly this is an accumulation of ruin. This work is wrought from the artist’s past year of life after the death of her father, Kamal (15 June 1948 – 22 May 2015), and should be understood as a multi-faceted portrait. This portrait confronts architecture, changes it so that walls crumble slowly from shed tears. This portrait aches from the severed base of another artwork, a statue of Ganesh, that was stolen from where Kamal had it placed. This portrait culminates with the remnant of a tree to which Kamal would pray, coincidentally cut down following his too-soon passing. What is it about ruins? Do we embrace ruins because monuments are for assholes and memorials are for losers? Ruins stand, or don’t, for those who refuse to die. What happens when the heartbeat that, weeks shy of beating for sixty-nine years, refuses to beat any longer? What happens when the statue that, after almost fourteen years bolted into the downtown cement, is pilfered, leaving the shredded base as a sharp reminder of how indifferent this world can be? What happens when the tree that had stood for some time well after the heart started beating but before the statue had been set in place, is diagnosed with an untreatable disease and cut down without notice? How can you brace yourself for something that appears without warning? This is how the rain comes.

Rain, or water to be precise, is central to the trilogy of works in this exhibit: the wall falls into ruin under the slow pressure of a constant leak of water, a concoction from the Ganga (which the artist collected following prayers marking the one year anniversary since her father passed) and water from Calgary’s Glacial H20, both of which purport healing properties. Ganesh – the god of beginnings, guardian of entrances, and remover of obstacles – is noticeably absent here and is only potentially identifiable by a lotus flower and a mouse perched atop a large brass pedestal, decorated on all four sides by elephants that were once rejoicing for the dancing deity above them. Mice, sometimes even rats, are depicted close to his feet as a symbol for desire, and his ability to overcome this desire and destroy all obstacles. Now, we are left with an empty space where Ganesh once stood. The festival of Ganesh Chaturthi sees worshippers idolize the elephant-headed god and by its end submerge these idols in water. This submerging, dissolving of the statue, is referred to as visarjan, or farewell … another loss. It was not the absence of water that lead to the tree’s demise. What kind of tree was it anyway? Does it even matter? It was a tree, and it was a place of meditation, of promise, and now it, too, is gone. How does an accumulation of loss begin to address the over-abundant presence of memory? Mehra’s portrait(s) deny the image of her father, just as the violence that has spurred this work is an interruption to her reality. And still, the memory persists. Memories will always withstand that which the real world allows to be washed away too easily. Count them: the time your cricket team scored the winning run, the day you met your wife-to-be, the moment your daughter was born, the day you bought your first car, when you decided to feed your family instead of following your dreams, the sand in your feet, the sweat in your shirt collar, the time your heart stopped.

In Mehra’s unconventional shrine to her own loss, she asks, How do we come to know violence? There is an implied relationship here — that we might actually be identified, that to know is fathomable, or even that one person’s violence is universal. The set up is an uphill battle, just as it should be. There are so few days in this life and each one is never the same as before.

-K.M.

Divya Mehra’s practice explores diasporic identities, racialization, otherness, and the construct of diversity. Her work has been included in a number of exhibitions and screenings, notably with Creative Time, MoMA PS1, MTV, and The Queens Museum of Art (New York), MASS MoCA (North Adams), Artspeak (Vancouver), The Images Festival (Toronto), The Beijing 798 Biennale (Beijing), Bielefelder Kunstverein (Bielefeld), and Latitude 28 (Delhi). Mehra holds an MFA from Columbia University and is represented in Toronto by Georgia Scherman Projects. She currently divides her time between Winnipeg, Delhi, and New York.

Kegan McFadden is a writer, a curator, and an artist. His research into magazines produced by artists in Canada during the 1990s, Yesterday was Once Tomorrow (or, A Brick is a Tool) included The New Gallery’s short-lived periodical, Texts (1989-1993), and will be the subject of the forthcoming book co-published by Plug In Editions and Publication Studio (Fall 2016). His exploratory writing in response to visual art has been commissioned by artist-run centres and magazines throughout Canada over the last decade. He has developed a curatorial and collaborative working relationship with Divya Mehra since 2007.