MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

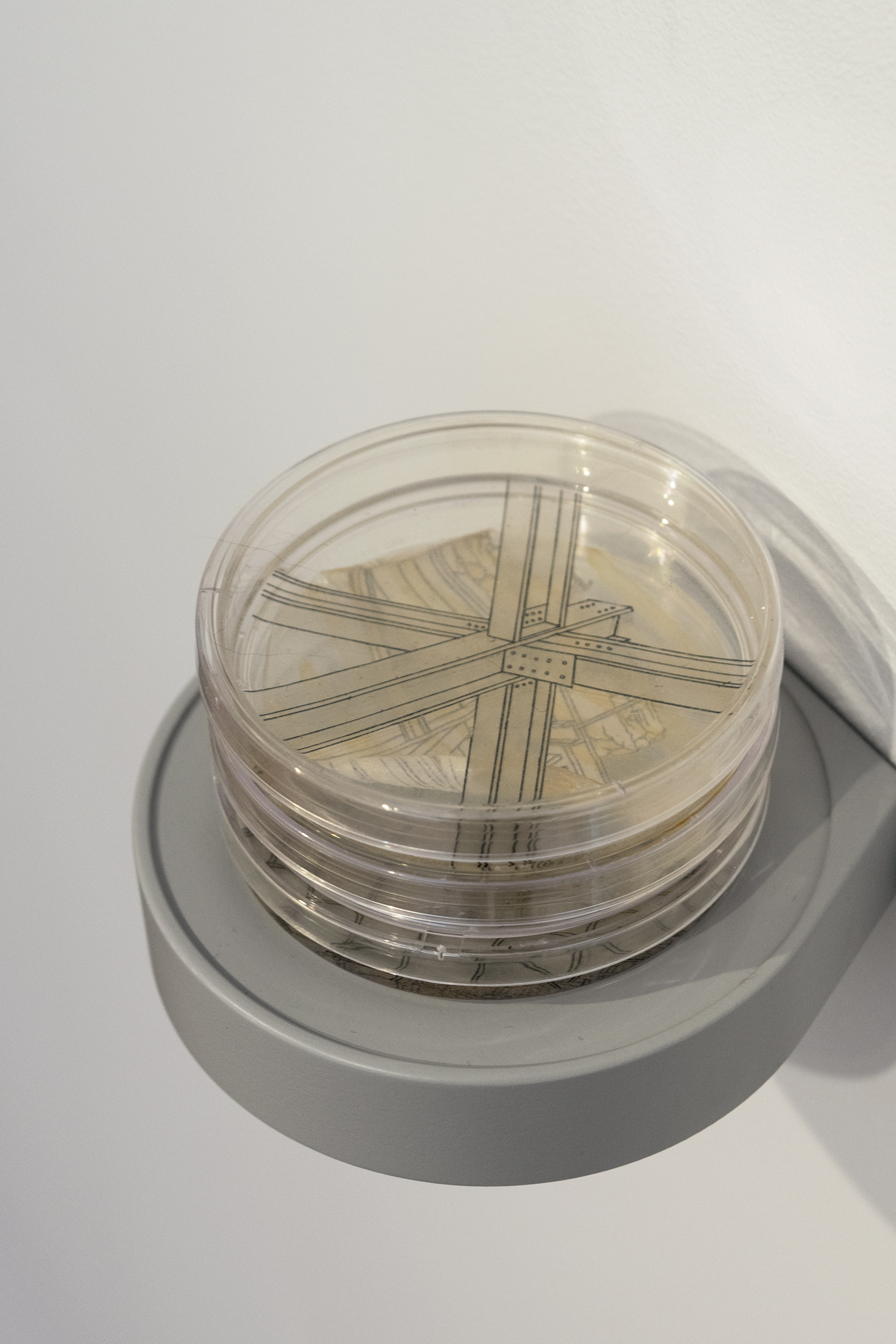

Jill Ho-You – In The Dust I, 2015

Inversion

Jill Ho-You

January 11—February 9, 2019

Exhibition Description /

Inversion engages with the anxiety, fear, and speculation about the future of the planet by imagining the world if the Anthropocene reaches its predicted negative climax of uninhabitable climate change, shrinking biodiversity, and unsustainable development. Imagining what remains after the projected extinction of humanity, the work explores the idea of systemic failure by examining the relationship between the biologic, environmental, and man-made. Blurring the lines between the human body, the natural and the manufactured landscapes, the exhibition traces a speculative history of the Earth from creation to destruction, questioning and emphasizing the role of human industry through the conspicuous absence of people.

Exhibition Text /

in·ver·sion

/inˈvərZHən/

noun

Inversion is a term that can be understood to explain many different processes, all which involve going back in position or time. This exhibition explores the various forms of inversion that relate to the transformation of the panoramic landscape. Jill Ho-You opens a new space for reflection, giving visual form to widespread public anxieties about how industries may have impacted the land beyond repair. Inversion articulates the conflict between the human need to harvest natural resources for survival, the modern world’s wanton demands of consumption, and the pressing concern to take steps towards returning our fragile planet back to its original state of nature.

The first recorded usage of the word inversion occurred in 1598. In John Florio’s A World of Words, “inversion” is defined as “a turning inside out, or upside down, a misplacing.”1 It seems like no accident that the word used to describe a process of reversal originated during the historical epoch that marked the shift from local subsistence farming to large-scale agricultural operations. The term emerged at the dawn of the awe-inspiring yet equally terrifying force of the industrial sublime. Like the original conception of the sublime, in which viewers encounter the overwhelming grandeur and scale of natural geological formations like mountain ranges, and contemplate the smallness of human existence in relation to the forces of nature, the viewing of massive industrial sites similarly evokes emotions of fear and awe in equal parts. But what differentiates the industrial sublime from the traditional conception of the sublime is that human industry, rather than nature, is responsible for this conflicted emotional reaction to the landscape. Large scale industrial projects transform vast tracts of land into sites of extraction. Viewing these industrial sites causes us to reflect on the powerful yet possibly irreversible consequences of industrial progress.

To think about inversion is to engage with the limits to our understanding of cause and effect. Since the results of resource extraction are cumulative, it is difficult to imagine the effects of our local actions on a global scale. The problems are so big and abstract that it seems impossible for any individual person to explore, for instance, the full effects of any one industrial project on the global ecosystem, let alone to interject in debates about resource extraction. The solution to environmental degradation, like the word inversion itself, exemplifies multiple conflicted meanings at once. It signifies both a necessary reversal back to an original state and the misplaced probability or likelihood of that effort to ever return back in time to force a clean restart.

The art objects on display are not exempt from the activity of transforming natural materials into objects for human consumption. On the contrary, Ho-You’s practice foregrounds such transformative processes, implicating viewers as complicit in looking at the objects on display, daring us to take pleasure in viewing the marvelous destruction of the natural world. Raw materials such as organic paper harvested from trees have been irreversibly transformed by the human hand, and run through a mechanical printing press. Such practices function to maximize, transform, and at times also to preserve the fragility of these materials. The iconography similarly reflects this tension between the natural and the manmade. In Ho-You’s series, Natural History, we see the earth just being formed. Later on, we see resources taken from the earth. Finally, waste products sink back down into the earth and begin to be reclaimed by natural processes.

The process of natural inversion is further exemplified by the prints embedded inside of the petri dishes. Here, the narrative of human progress is inverted. It is not the skill of the artist’s hand which completes the work of art. Instead, the aesthetic requirement of human mastery over nature is given up. Through a kind of collaborative process, the sequence is reversed so that the natural organisms of mold and bacteria may begin to complete the process of transformation inside the microclimate of the petri dishes. In this process-based experiment, the environment is left to complete the final work of art. The materials are transformed. They are again alive and growing back towards their original status as organic objects. Yet these new organic lifeforms may never fully return back to become the same raw materials on which they have grown. Their inability to complete the process of inversion in this new microclimate marks both the start of something new while simultaneously marking the site of a perpetual crisis.

There is an unsettling symmetry between beauty and destruction to be found in the degradation of the natural world. Within Ho-You’s In the Dust prints, we find a post-apocalyptic scene, with only traces of human life left behind as the planet reaches the end of earth time. The conspicuous absence of humans in this series offers a way for us to explore our anxieties about the longer duration of geological time as fundamentally inconsistent with our own meager human existence. Lapsed utopian dreams of human enterprise are reflected back at the end of earth time in ways which allow us to reflect on the interconnectedness between human systems and natural processes. The registration of human traces left behind show a world that has been hollowed out, extracted, exposed bare, even as the earth begins to invert and crumble inward on itself. These inverted images haunt the prospect of ever returning to finish the changes that we have started. Once the landscape has been transformed, it seems difficult to move in the opposite direction, to explore the possibilities of ever returning the terrain back to its original pristine state. In fact, the terrain itself is always undergoing change, which calls into question any conception of the natural world as stable.

— Rich Cole

1According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin of the word “inversion” reads as follows: “1598, J. Florio, Worlde of Wordes; Inuersione: an inuersion, a turning inside out, or upside downe, a misplacing.” Spellings in the essay body have been updated to accord with today’s conventions.

Biographies /

Jill Ho-You is an Assistant Professor in Print Media at the Alberta College of Art + Design. Her practice explores the intersection of trauma, embodied memory and the environment through a mixture of print media, installation, and drawing. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including solo exhibitions at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia and at Alberta Printmakers in Calgary, AB. She has also participated in numerous group shows such as at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Japan; International Print Center New York, NY; and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art, ROC. She is the recipient of grants from the Canada Council for Arts and Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and has participated in residencies at Open Studio in Toronto, ON and St. Michael’s Printshop in St. John’s, NL.

Rich Cole is an educator, writer, and cultural historian. His recent writings appear in Cartographies of Exile: A New Spatial Literacy (Routledge Press); H.D. and Modernity (Presses de l’École Normale Supérieure); Joyce and the Law (University Press of Florida); Modernism and Affect (Edinburgh University Press), and Shift: Journal of Visual and Material Culture. He is a commissioning editor for the experimental poetry journal Wave Composition and a contributing editor at ASAP/J, the contemporary art journal for the Association for the Study of the Arts of the Present. He teaches at Alberta College of Art + Design.

Territorial Acknowledments

TNG gratefully acknowledges its home on the traditional territories of the people of the Treaty 7 region, including the Blackfoot Confederacy (Kainai, Piikani and Siksika), Métis Nation of Alberta Region III, Stoney Nakoda First Nation (Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley), and Tsuu T’ina First Nation. TNG would also like to acknowledge the many other First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have crossed this land for generations.