MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

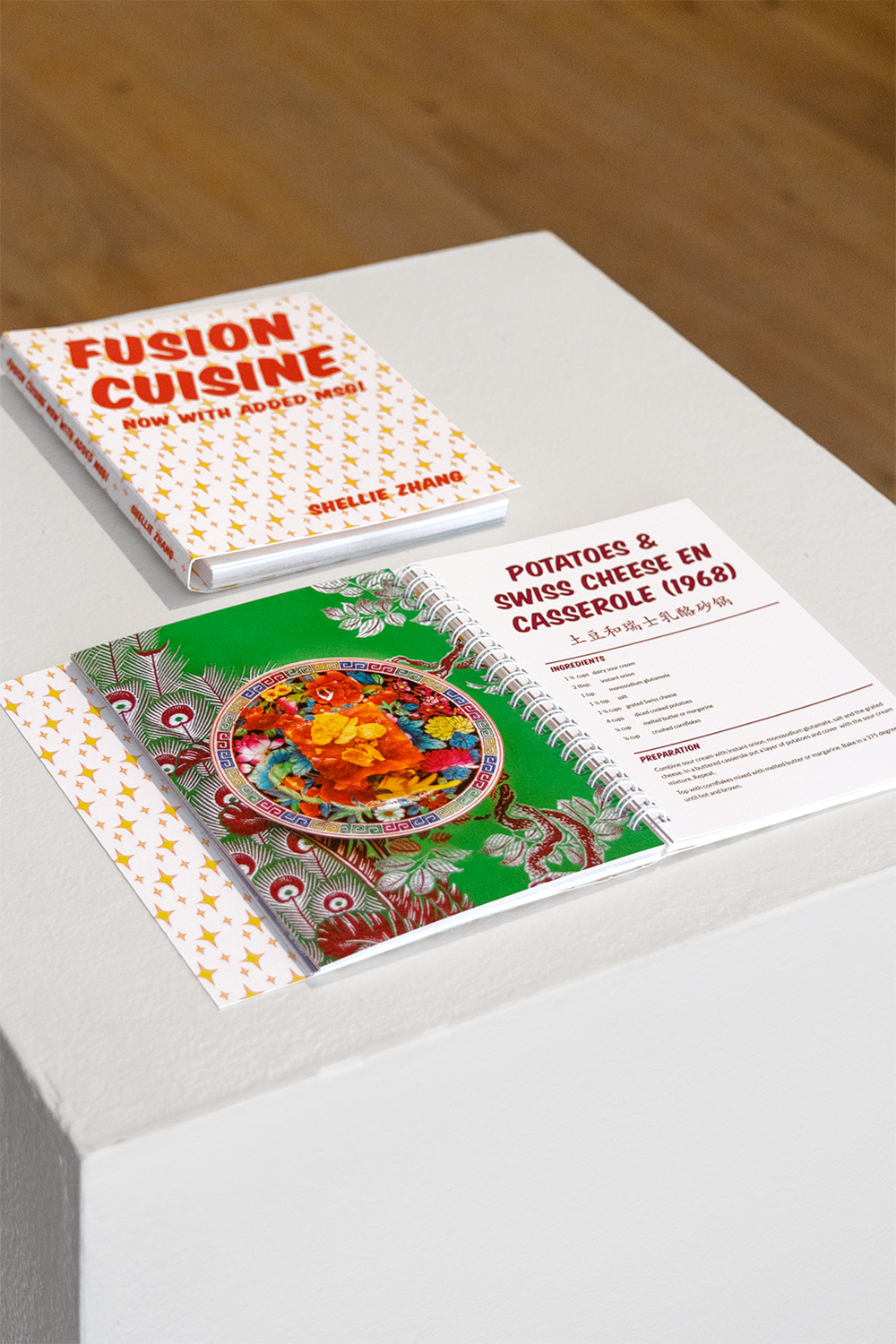

Shellie Zhang – No MSG (In Memory of Lee Garden), 2017

Accent

Shellie Zhang

May 25–June 22, 2019

Exhibition Description /

Visceral and often communal, food is one of the most accessible ways to engage with a culture. Through its consumption, creation and interpretation, food possesses the unique capability to extend beyond itself corporeal restrictions to reflect individual and shared stories, as well as historical and political climates. Combining a history of product marketing alongside archival materials from the Toronto Star, Accent presents a case study of the nuanced and racialized undertones within the everyday.

In 1968, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter to the editor from one reader describing radiating pain in his arms, weakness and heart palpitations after eating at Chinese restaurants. The reader mused that a combination of cooking wine, monosodium glutamate (MSG) or excessive sodium might have spurred these reactions. Reader responses poured in with similar complaints, and scientists jumped to research the phenomenon, centering on the glutamic salt, MSG. Not long after, the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” was born.

When first introduced, MSG was not the antagonized evil that it is often known as today. MSG was commonly used in North America, often marketed under the brand “Accent” and recommended as another shaker in addition to salt and pepper. As more paranoia came to surround MSG, Western attitudes shifted, assigning the negative connotations of MSG solely on Chinese cuisine. To this day, despite its widespread usage, it is frequently only Chinese and East-Asian restaurants that are forced to attest that they do not use the seasoning.

Exhibition Text /

Our Chemical Romance: MSG as a Love Story

You can hear an accent but can you taste it? Is it salt? Soy sauce? The brown edge of the tofu coming off the wok? Something else? What is it? Shellie Zhang’s Accent asks us to dwell in the what-we-can-taste-but-cannot-name. It is the shade of difference that is both obvious and obscure. Monosodium glutamate is not Chinese. However,there is a whole history of racism and fear that has made MSG Chinese. Zhang’s Accent brilliantly tracks the complexity of this history — of how a chemical compound produced for, and popularized by, industrial food giants such as Campbell’s Soup has left us with a legacy of anxiety and influence that is as much about “real” Chinese food as it is about the artifice of taste.

You can hear an accent. Maybe you can even taste Accent. Maybe you can isolate an accent, the difference that comes from displacement, from Accent, or the difference that comes from a chemical compound. Maybe you can differentiate difference from artifice. But maybe that is not the point. Zhang’s Accent is a love story about our chemical romance with MSG, yes, but also with what MSG represents. It points us to the desire to isolate difference even as that difference is the site of desire.

Zhang’s work illuminates the chemical romance of MSG. It enchants and repels. Manufactured to make vivid food that was merely bland, MSG romances in technicolor. It is about the ease of falling for that which is so bright, so saturated in intensity that it veers dangerously into the lurid and the gaudy. Falling for MSG is easy. It is a shot of scrumptiousness across the trough of tastelessness.

And so, “Baked Hungarian Chicken” (1935), “Stuffed Savoy Cabbage” (1955), “Chicken Italiano” (1957), “Hockey Short Ribs” (1970), and “Mississauga Fried Chicken” (1970) — all of which you will find in Zhang’s artwork, “Fusion Cuisine with Added MSG, 2016 – 2018.” Each of these dishes made delectable by a generous helping of MSG. Each one is, arguably, as Chinese as a can of industrially-manufactured tomato soup. It’s hard to taste the teaspoon, or 1 ½ teaspoons, of MSG, often referred to only by its brand name, “Accent,” called for by each recipe. But Zhang lets us see the Accent. Plating each dish on surfaces dense with chinoiserie, and saturating her images of each dish in the acid-hued colours that evoke the height of the technicolor dye-transfer era, Zhang allows us to see what we cannot taste. Here, the pleasures of dishes that are easy to fall for, dishes that are bright with promises that make the mouth water.

But such pleasures are risky. Too quickly, the cure for tastelessness can itself seem tasteless.

Here, as Zhang shows so beautifully through her careful research and exhibition, the anxiety and fear of difference sets in. Falling for MSG was too easy. Falling out of enchantment with it involves marshalling the ugliness of xenophobia and racism that would leave us with “Chinese restaurant syndrome” and the ubiquity of neon “No MSG” signs in Chinese restaurants across the continent. Behind the quiet hum of each neon sign is a long and unquiet history of discrimination.

And so, there is MSG as contraband, as white powder in plastic bags, as syndrome and sickness. This turn, too, as Zhang shows, is racialized. There is nothing particularly Chinese about MSG. There is only guilt by association. There is only condemnation without evidence.

Romance is risky and love stories don’t always end well; Zhang gives us a joyous ending fit for the complexity of the MSG itself. She invites us to taste the accents that make our lives richer and more flavourful. She reminds us not to fall for easy vilifications of the unnatural. Come in. Sit down. See Accent.

–Lily Cho

Shellie Zhang (b. 1991, Beijing, China) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Tkaronto/Toronto, Canada. She has exhibited at venues including WORKJAM (Beijing), Asian Art Initiative (Philadelphia) and Gallery 44 (Toronto). She is a recipient of grants such as the RBC Museum Emerging Professional Grant, the Toronto Arts Council’s Visual Projects grant, and the Canada Council’s Project Grant to Visual Artists. Recent projects include a residency at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Creative Time Summit, and publication with the Art Gallery of York University (AGYU).

By uniting both past and present iconography with the techniques of mass communication, language and sign, Zhang’s work deconstructs notions of tradition, gender, identity, the diaspora, and popular culture while calling attention to these subjects in the context and construction of a multicultural society. She is interested in exploring how integration, diversity and assimilation is implemented and negotiated, how this relates to lived experiences, and how culture is learned and relearned.

Lily Cho is an Associate Professor in the Department of English at York University. Her book, Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada, explores Chinese restaurants as sites of Canadian culture. She has published essays on vernacular photography in Interventions, Citizenship Studies, and Photography and Culture. Her current project, Mass Capture: Chinese Head Tax and the Making of Non-Citizens, looks at identification photography as a technology through which racialized migrants are excluded from citizenship.

Territorial Acknowledgments

TNG gratefully acknowledges its home on the traditional territories of the people of the Treaty 7 region, including the Blackfoot Confederacy (Kainai, Piikani and Siksika), Métis Nation of Alberta Region III, Stoney Nakoda First Nation (Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley), and Tsuu T’ina First Nation. TNG would also like to acknowledge the many other First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have crossed this land for generations.